They’re less well known than Cook, Magellan and Champlain, but Tammy Norgard and her fellow scientists at Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans are just as deserving of the title of explorer.

In a series of expeditions over the past three years, Norgard and her colleagues have discovered massive underwater volcanoes, strange new habitats and never-before-seen organisms — all deep beneath the ocean’s surface just a few hundred kilometres off the coast of Vancouver Island.

It’s a vast uncharted territory that Canada declared an Offshore Pacific Area of Interest in 2017 — the first step toward creating a Marine Protected Area under Canada’s Oceans Act.

Before that happens, however, the government needs to understand what’s there, which is why the Pacific Seamounts Expeditions are so important, Norgard says.

“We are really just collecting baseline information so we can know what’s out there and so we can set up protections that will be appropriate for the area.”

This year, the scientists, in partnership with the Nuu-chah-nulth Nations and Ocean Networks Canada, returned to the scene of their greatest discovery: a massive underwater volcano known as the Explorer seamount.

First spotted in 2018, Explorer rises 2.5 kilometres from the ocean floor, rivals Mount Baker in height and gives life to an ancient city of glass sponges that scientists have nicknamed Spongetopia.

Norgard, the expedition’s chief scientist, said her team expected to see more of the same on its two-week expedition.

Instead, they found areas of even greater diversity on the other side of the Explorer seamount.

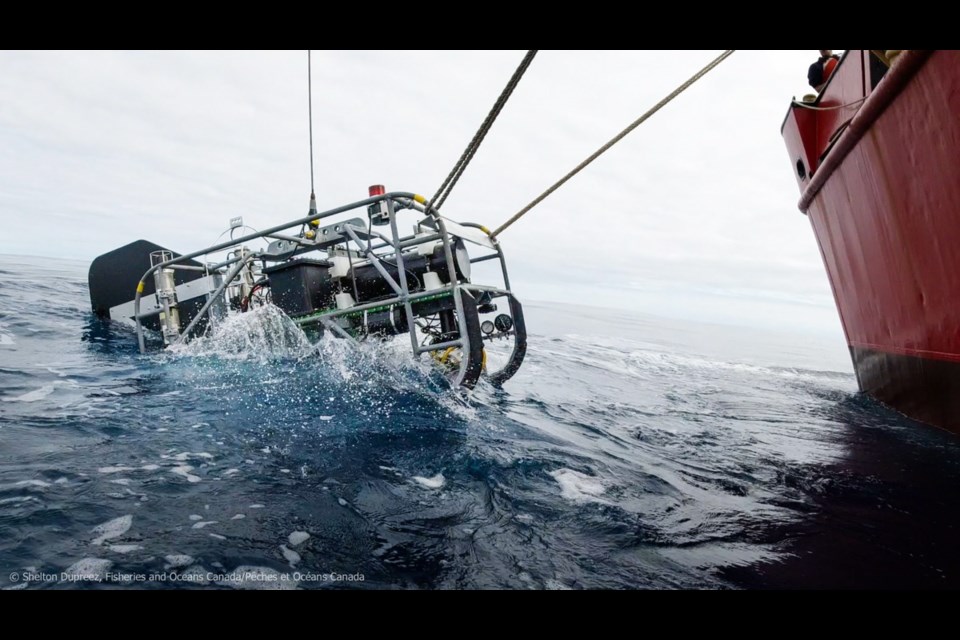

Using a submersible “drop camera” lowered into the ocean from the Canadian Coast Guard vessel John P. Tully, scientists uncovered a vast forest of coral and sponges, crabs and sea stars that they are calling Coraltropolis.

“You have no idea what you’re going to see,” Norgard said. “It’s so exciting. You hit the [ocean] floor and like, ‘Wow!’ The first thing you see is like a fish go by … or there’s an octopus sitting there, or it’s just like this habitat full of all these sea cucumbers.”

The team also mapped 10 previously uncharted seamounts and captured rare video footage of a salmon shark apparently scratching itself on a barnacle-covered log.

Caroline McNicoll, a communications specialist with Fisheries and Oceans, said it’s believed to be the first time such images of a shark have ever been captured.

During the voyage, scientists and crew members livestreamed their findings to 38 countries and did ship-to-shore talks with people at science camps and in the Nuu-chah-nulth communities, McNicoll said in an email.

Joshua Watts, who took part in the expedition as a representative of the Nuu-chah-nulth Nations, described it as a “life-changing” experience.

“I didn’t have much experience going out that far to sea,” he said.

“Every day there was something new happening, and there was some new information coming in, or there was some new uncharted area that we were going over.

“I’m probably going to remember that trip for the rest of my life.”

Watts said the Nuu-chah-nulth Nations take seriously their stewardship of the land and water, and the seamount expeditions aligned with those values.

“Even though this is 150 kilometres offshore, the organisms and the life there is so relevant to our territory,” he said. “It’s all connected.”

Norgard hopes others learn to recognize those connections through the seamount expeditions and the ongoing research.

“I really want to get out there to see what’s out there and share it with everybody, so we can all understand that the ocean is a larger ecosystem than just what you see on the beach,” she said.