U.S.-based Parabon NanoLabs has gained international attention for its groundbreaking use of genetic genealogy to solve cold cases, including the 1987 murder of a Saanich couple on a road trip in Washington state.

But while Canadian police are quietly using the tool to solve murders, B.C.’s privacy commissioner says there are serious privacy implications around how DNA is used and shared by genealogy companies.

“Your DNA is probably the most sensitive personal information that one can imagine,” said information and privacy commissioner Michael McEvoy. Yet B.C.’s privacy laws don’t cover technological advances such as genetic genealogy, leaving few guidelines for police on how to use such technology, said McEvoy, who wants to see more significant protections.

Genetic genealogy can find suspects not because they surrendered their DNA, but because their relatives provided DNA on open-source consumer genealogy websites.

“When you’re consenting [to the terms and conditions], you’re not only consenting to [use of] your own DNA, but you’re in effect consenting on behalf of everybody you’re related to,” McEvoy said. “Our laws of consent are not really designed for something like this.”

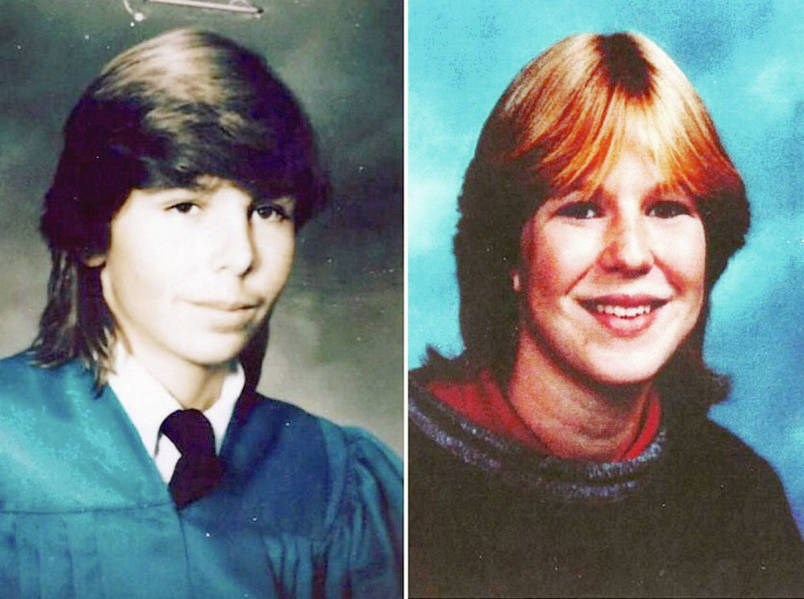

In the Washington state murder case of 18-year-old Tanya Van Cuylenborg and 20-year-old Jay Cook of Saanich, police identified William Earl Talbott II as the killer after genealogist CeCe Moore helped Parabon NanoLabs build a family tree for Talbot, based on DNA recovered from the crime scenes.

Talbott was identified through genetic matches with two second cousins. Police kept him under surveillance until they could grab a paper cup that fell from his truck. The DNA came back as a match and Talbott was found guilty of the crime in 2019.

The same technology was used to catch the Golden State killer, Joseph DeAngelo, who pleaded guilty to murdering 13 people and raping about 50 women in California during the 1970s and 1980s.

Parabon offers three services for police: genetic genealogy, which identifies possible suspects by searching for relatives in public databases and building family trees; DNA phenotyping, which predicts the physical appearance and ancestry of an unknown person based on their DNA; and kinship inference, which determines kinship between DNA samples to six degrees of relatedness.

While U.S. police have often disclosed when genetic genealogy helped produce the missing link in a cold case, Canadian police have been more tight-lipped.

The RCMP entered into a $98,000 contract with Parabon NanoLabs in 2018, but the national force will not say how many times or in how many cases investigators have used genetic genealogy.

Robin Percival, a spokesman with RCMP national headquarters, said the RCMP does not disclose which investigative techniques are used. Percival said genetic genealogy is a relatively new investigative tool that can be used when other forensic techniques have been exhausted.

A case involving genetic genealogy has yet to be tried in Canadian courts, so it’s unclear how it will fare legally.

“Should a Canadian case go through the court system with a genealogical DNA component, the decisions rendered will also have an effect on how police use this investigative technique,” Percival said.

The RCMP has not yet completed a privacy-impact assessment for the use of genetic genealogy, but said it has begun consulting with the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. It’s researching legal, ethical, privacy and practical implications for use of the technique and developing a national policy that will provide guidance to investigators, Percival said.

The Vancouver Police Department used Parabon NanoLabs and DNA phenotyping to create a composite sketch of a murder suspect using DNA found in the Vancouver apartment where Edgar Leonardo was killed in 2003.

Spokeswoman Const. Tania Visintin said the department has used the technology on cold cases, but has not had any success solving crimes with it. “We choose to use genetic genealogy when we have DNA and have no suspects identified in the file and no hits on CODIS,” she said, referring to the Combined DNA Index System.

Victoria defence lawyer Michael Mulligan said because DNA evidence can point to multiple people within a family tree, it’s important that investigators have other evidence to corroborate the DNA match. He said a genetic match through DNA can provide a good starting point for police, but should not close the book on the investigation.

“I would be very concerned if there was absolutely nothing else connecting the person to the crime,” said Mulligan, who noted that genetic genealogy can also be useful in clearing people who are wrongfully convicted.

Last year, the Toronto Police Service worked with Texas-based genomics company Othram to solve the 1984 killing of nine-year-old Christine Jessop. DNA found on Jessop’s underwear pointed to Calvin Hooper, a man who died in 2015. Guy-Paul Morin, who had been wrongfully convicted, was exonerated through DNA in 1995.

Paula Armentrout, vice-president of Virginia-based Parabon NanoLabs, said in an email that use of its technology does not represent a violation of privacy. For investigative genetic genealogy, Parabon uses only publicly available databases that have special law-enforcement programs, such as GEDmatch and FamilyTree DNA, she said.

“The individuals in those databases have chosen to allow their DNA to be used,” she said. Ancestry DNA and 23andMe do not have law-enforcement programs, Armentrout said.

DNA phenotyping uses DNA left behind at the crime scene, so “we are predicting only things about the unknown person-of-interest that they would know about themselves by looking in a mirror or knowing their family history,” Armentrout said.

McEvoy is concerned that genealogy companies that collect DNA have too much power over how to use and disclose genetic information. Consumers must agree to the terms and conditions, but McEvoy said they are often pages long and full of complex legal jargon that people don’t fully understand.

Changes could be coming to the Personal Information and Protection Act, which was passed in 2004 — a special legislative committee will review the act, hear from stakeholders and make recommendations in 2021.

McEvoy called for rules governing when police departments can use genetic genealogy. “It may require some judicial oversight to give police authority to make sure they are using it in a proper way, a proportionate way, in a way that will bring the greatest benefit to society as a whole.”