For 85 years, the William Head Quarantine Station in Metchosin was Canada’s major port of entry on the West Coast for immigrants arriving by sea. In one of the more memorable — and poignant — episodes from its history, the station served as a receiving centre for the Chinese Labour Corps, a group of more than 90,000 men recruited by Britain in the First World War to work as labourers on the battlefields of France and Belgium.

It began innocently enough with a simple, heartfelt letter home:

My Dear Father and Mother-in-Law,

Your son-in-law left on the 5th month, 3rd day. We went aboard ship and started on our journey and travelled till the 24th. We have arrived in English Canada from where we take a train and in about 16 days we will arrive in France.

My journey has been one of peace and tranquillity under the protection of the Heavenly Father and I have met with no dangers or hardships. Every day we have all we want, our eatables, clothing and everything we want are excellent.

I hope that Mother and Father-in Law have no anxiety about me. I hope that all the members of the Church prosper and don’t backslide because the Kingdom is near and we are controlled by destinies.

I thank you for taking care of my wife as she is bound to fret about my absence and furthermore present my compliments to the two families, my sisters-in-law and the eldest daughter-in-law, and I wish you a tranquil farewell.

Your Son-in-Law

Joe Hwei Chun, in reverence.

(J. Robert Davison, “The Chinese at William Head, A Photograph Album,” British Columbia Historical News, 16, no. 4 (1983), 19.)

Joe Hwei Chun was going to need all the faith he could muster, as he was in for the shock of his life. When he arrived at the William Head Quarantine Station on April 18, 1917, he was in transit with 2,056 of his countrymen on the Empress of Russia, bound for the Great War, not as a soldier exactly, but as a worker in a volunteer “clean-up” army. He had joined the Chinese Labour Corps in Weihaiwei, China, to replace non-combatant Allied troops who were being sent to the Western Front as Canadian and British casualties mounted. In total, 84,473 Chinese labourers would join the CLC and be held while in transit at the William Head Quarantine Station.

They were being sent to the Ypres Salient, a curved swath of high ground from which, in 1917, the British believed they could sweep down to regain the German-occupied Belgian seaports with their deadly submarine bases in the English Channel. For the Allies, it would be a massacre with more than half a million casualties in five months; villages such as Poelcappelle and Passchendaele were annihilated. It was the CLC’s task to repair roads, drive supply vehicles, retrieve unexploded shells and bury the dead.

The reality meant searching for bloated and blackened corpses among the monstrous ruins of ancient hamlets from Lillers to Langemark.

It was a clandestine operation from the outset. From William Head, most were sent to Vancouver, transported in special trains to Halifax and shipped to Dunkirk. The secrecy was necessary for fear that Germany might discover the enterprise, or worse, that Chinese communities across Canada would try to prevent their countrymen from continuing on.

In 1903, the head tax levied against Chinese immigrants had been increased from $100 to $500, but Conservative prime minister Robert Borden waived the tax for CLC members with the proviso that trains carrying them across Canada be locked and guarded. Secured railway cars each carried 50 labourers and four armed guards, while special police discreetly guarded platforms along the way.

Most were recruited from the very outer edges of China and Mongolia, and some were likely unaware of the legislated racism against Asians entering Canada. Unlike the 17,000 Han Chinese in the CLC, these particular “soldiers” were largely uneducated in the ways of Western culture and alien even to the rest of China. The one thing they were was huge — most were over six feet tall. Those in Joe Hwei Chun’s brigade were from Shandong province in northern China; most of the others joined the CLC from Xinjiang, Gansu and Inner Mongolia.

The CLC left from Weihaiwei (Port Edward), a major port city in Shandong province, which opened to the Yellow Sea. Weihaiwei was a British garrison at the time with a huge naval base and sanitarium. There, each recruit was medically examined, inoculated, given zinc-sulphate eye drops to ward off trachoma and photographed. Their blue-grey uniform was a jacket containing a brigade number and a round cap marked “CLC.” Their kit was a simple bedroll, rice bowl and tin cup. Collectively, they looked more like a penitentiary chain gang than the proud, non-combatant Allied force they were expected to become.

Dr. Rundle Nelson was the chief medical officer at the William Head Quarantine Station at the time of their arrival, and it was he who had to deal with the sudden overcrowding. William Head was equipped to handle 800 people at best, but he knew that each chartered CPR Empress liner would carry far more. Increased numbers meant an increased threat of infectious disease. Nelson was on the wharf the day the Empress of Russia arrived at the William Head Quarantine Station and was reported to have said: “What shall we do if they have the smallpox?”

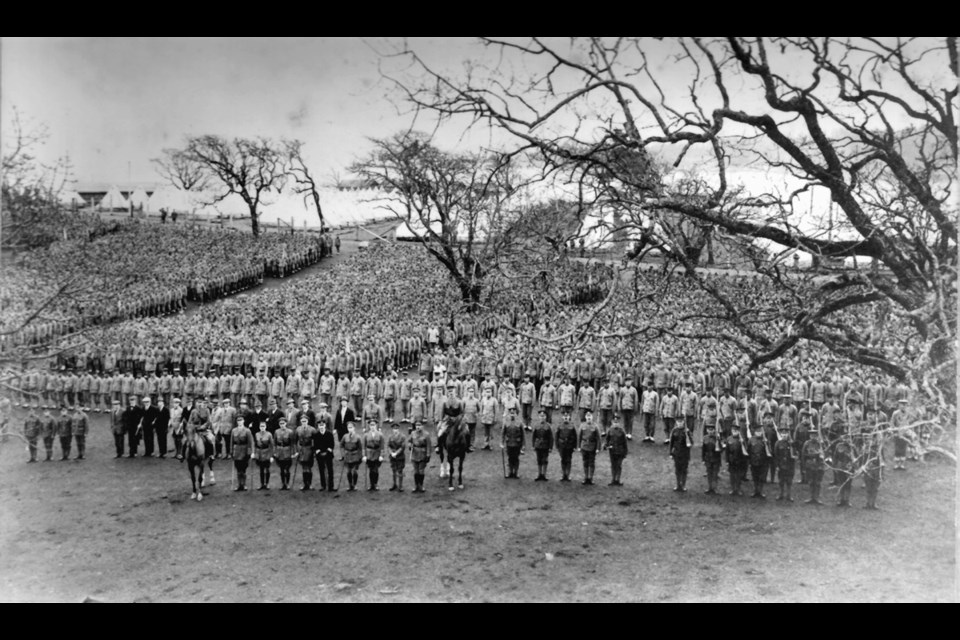

Nelson examined all 2,057 of them, and unceremoniously had the full complement removed from the ship and quarantined at his station for 14 days. Yet, week after week, the CPR ships Empress of Asia, Empress of Japan and Empress of Russia disembarked thousands of new CLC recruits at the station’s wharf. In July 1917, the Chinese Labour Corps had swelled to more than 30,000 men.

The Canadian Militia took official charge of the corps as they landed and created a fenced-off “coolie camp.” The CLC were accommodated in army bell tents right on the doorstep of William Head, and the 5th British Columbia Company of the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery immediately took over military discipline.

The artillery made one in every 20 members of the corps wear an armband designating a corporal’s rank, and it was through these intermediaries that information regarding camp rules and routines was supposed to be disseminated. But this top-down, authoritarian model was alien to the self-reliant nomads of the Mongolian borderlands, and as conditions deteriorated with the spring rains, discipline among the rank-and-file plummeted. Most were used to the autonomy and freedom of the China/Mongolia plateau, where they would not kowtow to the southern Chinese overlords.

To curtail the growing unrest, the artillery created Chinese work gangs who did laundry, cut firewood for the station, tended its vegetable and flower gardens, and made repairs to station facilities. Even in the evenings they dug trenches, dugouts and emergency gun pits, which made some suspect that the promise of a non-combative role in France might not have been the whole truth.

The CLC members seemed to adore the children of station employees, and made them and their families small woven baskets and other gifts. Homesick, they watched the children play, and when they could, taught them the rudiments of their language. Wary but indulgent, Garrison Artillery continued with its compulsory afternoon military drill. As the many brigades reluctantly paraded around the grounds, they were often followed by playful, dancing children, chanting in Hamelin fashion, “one-two, one-two” in a Cantonese/Mongolian mix.

The vast majority of the corps were cleared with dispatch at William Head and transported to Vancouver, where they faced an eight-day train journey across the country to Halifax followed by an equally long ocean passage to Southampton. The corps was ferried across the English Channel to France, where they disembarked on the beaches at Dunkirk.

Most peace-loving Chinese volunteers shrank in horror from the violence of the First World War. They were promised non-combatant duties, but that covenant was as hollow as the promise of sufficient food at William Head. The British Army could not be blamed entirely for this, as all of northern France and parts of Belgium came under fire from German heavy artillery or aircraft. From Passchendaele to Le Hamel, serial bombing by the new German Air Force massacred thousands of citizens, soldiers and Chinese volunteers alike.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission recorded some 2,000 deaths among the CLC during the Great War. Most of the dead were buried in unmarked graves in cemeteries in northern France and Belgium. Anonymous white military headstones offered little solace to a saddened wanderer, their brief inscriptions reading only: “A noble duty bravely done.” Without some sort of religious faith, Joe Hwei Chun, if he wasn’t killed outright somewhere east of Noyelles-sur-Mer, would surely have been driven completely out of his mind.

Quarantined: Life and Death at William Head Station, 1872-1959; © Peter Johnson, 2013. Heritage House Publishing, heritagehouse.ca