As we mark the centennial of the end of the First World War this weekend, we should think of people like Robert Parker, a Victoria man who died serving his country.

As we mark the centennial of the end of the First World War this weekend, we should think of people like Robert Parker, a Victoria man who died serving his country.

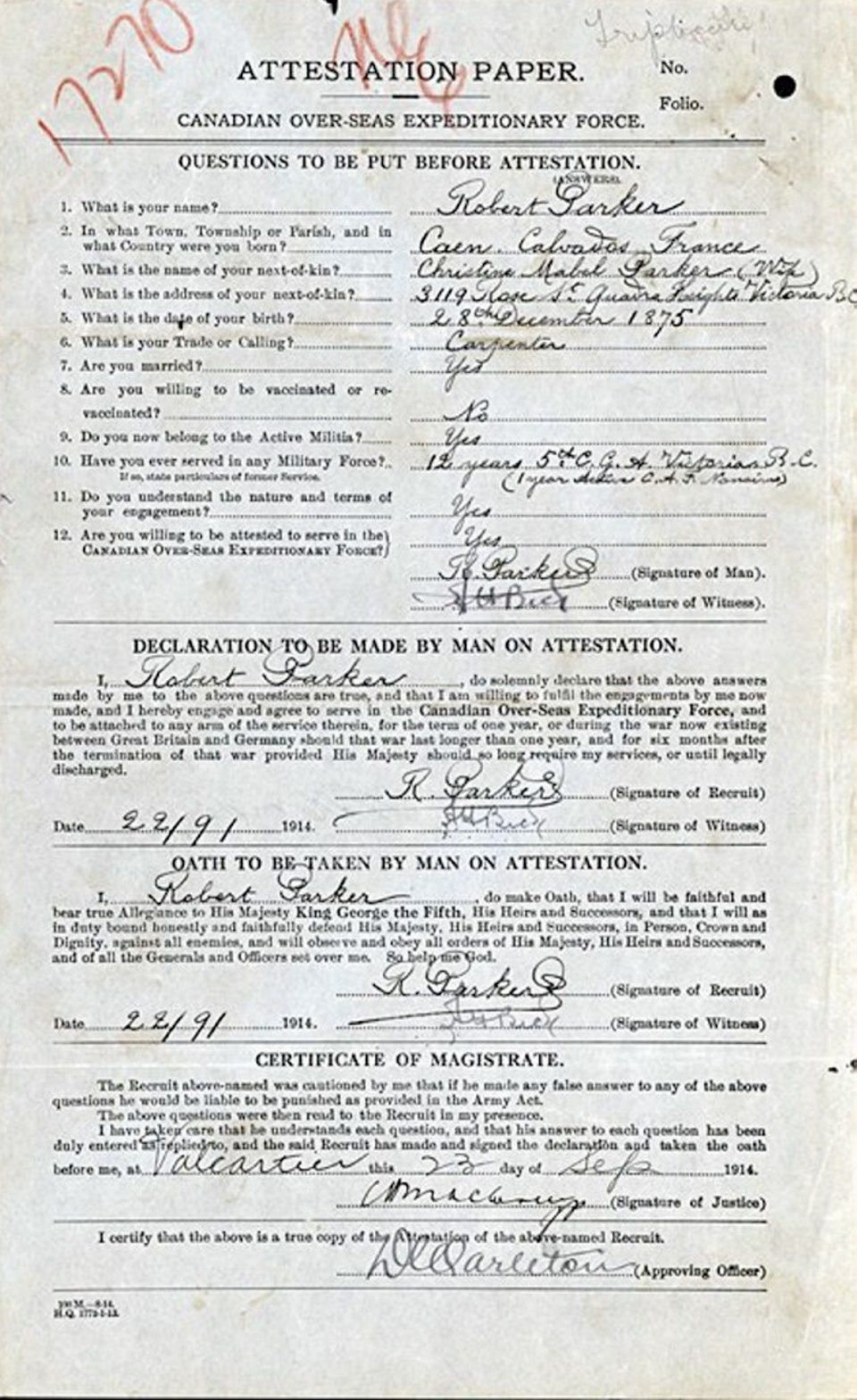

Parker might have seemed like an unlikely choice for the volunteer army that Canada hastily assembled in August 1914, in the heady hours after the start of the Great War.

Not only was he 38 — getting old for overseas service — but the military was reluctant to take men with families. Parker was married with seven children, ranging in age from five months to 14 years.

But Parker had experience in the militia, having served in Victoria for 12 years as a member of the 5th Regiment of the Canadian Garrison Artillery. Canada needed to assemble an army as fast as possible, and militia members could provide the experience that was desperately needed.

So when Parker volunteered to go overseas, his superiors didn’t hesitate. He was accepted and shipped to Valcartier, Que., where the Canadian army was being assembled. A month later, he was taken with 31,200 other Canadians to Salisbury Plain in England. The following spring, after helping train other soldiers, he finally saw action in France.

“The war came, and he had to go,” his last surviving child, Gladys George, said in an interview in 2005. Gladys was just two years old when her father sailed away.

There is not just one story about the Great War. There are more than 600,000 stories — one for every soldier who signed up to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

This is Robert Parker’s story.

- - -

Robert Parker was born in Caen, in the Normandy region of France, on Dec. 28, 1875.

Caen had a large, wealthy English population through the 19th century, based mainly on a busy trade route linking it with Newhaven, Sussex. Several English hotels and restaurants catered to the clientele from across the Channel. The Parker family was a key part of the English community.

Records at Caen City Hall show that Robert was the 16th child born in Caen to Frederick Parker, an English teacher, who probably worked at the private Protestant school at 75 rue St. Jean in Caen.

Frederick, who was born in Epping, Essex, in 1810, was married three times. The files at City Hall show that his first wife Charlotte Seaton had one child in Caen, six years after marrying Frederick, and François Robinard of the Caen archives guessed that “there were surely more elsewhere.” Frederick’s second wife Emma Crabtree had nine children, and his third wife, Lydia Miles, had eight.

Between 1842 and 1880, Caen City Hall registered 18 of Frederick’s children. He was 65 when his son Robert was born to Lydia in the family home at 1b rue de la Poudrière, and 70 when his last child, Christopher, entered the world.

Despite spending half a century in France, Frederick Parker always saw himself as English. He even ensured that his marriage to Lydia was entered in England’s central registry in London.

Robert Parker would have understood at an early age that he was English, not French. The names of the witnesses to the births of his children indicate that Frederick Parker was rubbing shoulders with the crème de la crème of the English expatriate community. One of Caen’s English landmarks, La taverne anglaise, was run by Robert’s uncle, Henry Humby.

In the early 1890s, when Robert was a teenager, Frederick decided it was time to go home to England — even though his wife and his children had all been born in France, and Normandy was the only home they had ever known. When Frederick and Lydia packed for England, Robert and his older brother Herbert had another idea: The Canadian West.

They headed to the Assiniboia district of the Northwest Territories, buying land just north of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s mainline so they could try their luck with farming. Their farm was south of the Qu’Appelle River Valley in the Summerberry district, east of Regina.

About the same time as the Parkers arrived, William and Mary Ann Newberry brought their family from England and took out a homestead in the Chickney district, north of Summerberry. Soon after, Robert met one of the Newberry daughters, Christine Mabel. They were married on March 30, 1898, and made their home on the Parker farm. Their first child, Florence Amelia, was born on Sept. 27, 1899.

The federal census taken in the spring of 1901 shows Robert, Christine and Florence on 160 acres in the Summerberry district. Robert’s brother Herbert isn’t listed, though — at the time, he was in England, visiting his parents as he made his way back to Canada after fighting in the Boer War as a member of Lord Strathcona’s Horse.

On July 29, 1901, Robert and Christine’s second child, Bessie Levina, was born. A few months later, the Parkers — as well as most of the Newberrys, Robert’s in-laws — packed their bags and moved to Victoria.

In June 1902, soon after arriving in Victoria, Robert signed up for the 5th Regiment of the Canadian Garrison Artillery, based at the Work Point Barracks. He remained in the militia for more than a dozen years.

Robert worked at first for John Taylor, who owned a sawmill near the north end of Government Street. The Parkers lived in the North Park area. Soon after, Robert became a carpenter, and the Parkers moved to a home at 1119 Quadra St., between Fort and View. The Newberrys lived just around the corner on View, toward Blanshard.

In 1905, Robert turned over to his brother Herbert his share of the farm in Saskatchewan. The following year, he received word from England that his father Frederick had died at the age of 96.

The Parker family kept growing, with the birth of Walter Frederick on Jan. 16, 1904, Maude Elsie on Feb. 12, 1906, Lillian Mabel on Oct. 16, 1910, Gladys May on July 4, 1912, and Robert Miles on March 10, 1914.

About 1912, the Parkers bought a lot at 3119 Rose St. in the new Quadra Heights district, just east of today’s Mayfair Shopping Centre. Robert and Christine drew up plans for a home they hoped to build as soon as they had enough time and money. In the meantime, they moved their family into a small shack that Robert built at the back of the property.

Through these years, Robert remained active in the local militia. By the summer of 1914, he was the company sergeant-major.

On the last weekend of June that year, the 5th Regiment gathered at Macaulay Plain in Esquimalt for exercises. A tug placed a target in Juan de Fuca Strait, about 3,000 metres offshore, and the militiamen started firing on it as soon as small craft in the area were convinced to leave. The Daily Colonist reported that the exercise was a huge success, with crowds needing “a very quick eye” to follow the artillery shells. The shells raised columns of water when they hit, followed by a second splash from the ricochet.

That same weekend, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, were shot to death by student Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo, Bosnia. A few weeks later, those shots would plunge most of Europe into what became known as the Great War.

In the calm before the storm, life in Victoria rolled along. Most of the excitement in July 1914 was on the waterfront. Locals could head down to Ogden Point to watch progress on the construction of the breakwater, which could finally be seen at low tide. And in late July, the infamous passenger liner Komagatu Maru went through the strait, heading west. Its passengers, potential immigrants from India, had been cleared by the William Head quarantine station in Metchosin in May, but were then refused permission to disembark in Vancouver.

By the end of July, the tensions that had been building in Europe finally erupted. Austria declared war on Serbia, which it blamed for the assassinations. Germany declared war on Russia and France, and as part of a master plan it had been preparing for years, tried to conquer France as quickly as possible by rolling through neutral Belgium. Then, on Aug. 4, Britain declared war on Germany. That meant that Canada, like it or not, was at war as well.

Victoria had three militia groups at the time — Parker’s 5th Regiment, as well as the 50th Highlanders, which had been established by the legendary A.W. Currie in 1913, and the 88th Fusiliers, formed in September 1912. All three had been conducting regular exercises, but quickly geared up for the trip to Europe that they realized was now inevitable.

On Sunday morning, Aug. 2, the Colonist published a call for a special parade of the 5th at 2 p.m. that day. Despite the short notice, 200 men showed up. The next day, the Colonist — in a rare Monday special edition — reported that more than 60 members of the 5th had volunteered for special duties in defence of the coast.

Over the next few days, dozens of men from the three militia forces volunteered to go overseas, and other men signed up to replace them in the local reserve units.

The federal government had strict guidelines for volunteers for overseas service. The age limit was 18 to 45 years, and to be eligible for service, volunteers had to be in the active reserve or have had military experience. And, the federal directive said, “other considerations being equal, the applicants will be selected in the following order: Unmarried men, married men without families, married men with families.”

Despite that, Robert Parker’s offer to serve was accepted without hesitation.

He was one of 470 men from the Victoria area approved for entry into the new Canadian Expeditionary Force by Aug. 11. About 100 who applied were rejected for health reasons — “some because of tender feet, bad teeth, cigarette heart and other slight ailments,” as the Victoria Daily Times delicately put it — and would only be allowed to work on home defence.

Even people outside the military were getting involved in the war effort. The Daughters of the Empire started collecting funds in August, with a goal of $100,000. The plan was to equip a hospital ship that would be offered to the British navy. A fundraising meeting was held at the new Royal Theatre to kick off the drive.

A local council of women opened a store for the sale of home-made pickles, sauces and other necessities, in order to provide employment for the dependants of soldiers heading off to war. The Victoria Patriotic Aid Society opened an office at Fort and Broad to collect money for the families of soldiers.

Other groups started working on relief for the Belgians. Over the next few weeks, they collected enough clothing to fill a boxcar.

The volunteer soldiers, meanwhile, spent several days getting ready to depart, and waiting for word on when they would be told to go. In the last week in August, both the Times and the Colonist published lists of names of the local volunteers — including Company Sergeant-Major R. Parker, of the 5th Regiment CGA.

Finally, on Tuesday, Aug. 25, the men of the 5th were told they would be leaving the next day. They were granted leave so they could spend a few hours with their friends, relatives and loved ones before they sailed off to fight.

The men gathered at Macaulay Plain at noon the following day, getting their bags ready and donning their equipment. At 1 p.m. the bugle sounded, and Lt. Col. William Norman Winsby, who was a school inspector when not in uniform, reviewed his followers. A few moments later, he ordered the men to march.

The men looked sharp in their crisp blue uniforms and forage caps, but something was missing — their rifles. They had been using Lee-Enfield rifles in their exercises, but the government had decreed that Canadian troops in the Great War would be issued Ross rifles instead. So the Lee-Enfields, the rifles the men knew and trusted, were left at home.

Parker and the other men marched first to Esquimalt Road, where they were met by the pipe band of the 50th Highlanders. The Highlanders band and the 5th’s own regimental band alternated as they marched along Esquimalt, then Bay Street to Government Street.

Children from Central, North Ward, South Park and George Jay schools had gathered on the lawn of The Empress Hotel, and sang Rule Britannia, The Maple Leaf Forever, Land of Hope and Glory and God Save The King as the soldiers passed.

The Highlanders and Fusiliers, who would leave two days later, formed lines on either side of the street as the men of the 5th turned on to Belleville Street to make their way to the Canadian Pacific Railway wharf, where the Princess Mary was waiting.

At the wharf another huge crowd, including mothers, wives, sisters and other loved ones, had gathered. The newspapers reported that the people in the crowd watched tearfully as the men marched up the gangplank, but broke into loud cheers of support when the boat pulled away at 3:40 p.m.

The men arrived in Vancouver at 9 p.m., and the next day boarded regular trains that would take them to Valcartier, Que., where the Canadian Expeditionary Force was being assembled.

If their families still in Victoria had any delusions about the risks the soldiers faced, they were dashed on Sept. 3. On that day, the first British casualty list, with 33 dead and many more wounded, was published in the local newspapers.

Parker arrived in Valcartier with the other men of the 5th, and all were assigned to the new 7th Battalion, which was also to be known as the 1st British Columbia Regiment.

It took several days for the military brass at Valcartier to process the thousands of men from across Canada. Parker’s paperwork was finally completed on Sept. 22. He listed his militia experience, and identified as next of kin his wife Christine as well as his mother Lydia, by then living in Brixton, near London, England.

As long as he was in the service, Christine would receive $20 a month from the government as a separation allowance. Robert also asked that $25 of his monthly pay be sent to his wife. That didn’t leave him with much spending money, considering he was being paid just $1.20 a day.

Parker’s medical report noted that he was five foot five, and had three vaccination marks on his left arm and a mole on the left side of his chest. At 38 years eight months, Parker was pushing the upper limit of the age range.

On Sept. 28, Parker and the other men of the 7th Battalion caught a train to Quebec, where they boarded the Virginian, the ship that would take them to England — eventually.

For the next three days, they watched from the Virginian as 29 other ships were loaded with people, supplies, clothing and equipment, a task that was finally completed at nightfall on Oct. 1. That night the Virginian and the other vessels were moved to Gaspé harbour, where they waited for their escorts to arrive.

The ships, carrying 31,200 Canadian soldiers, finally started to move at 3 p.m. on Oct. 3. It took three hours for all the ships to clear the harbour. Then, they crossed the Atlantic in formation — in three rows, with escorts on all sides — and arrived in Plymouth on Oct. 14.

Plymouth was picked as the landing spot at the last minute, when the threat from German ships made other ports unsafe, and it wasn’t set up to handle the size of the Canadian contingent. Parker didn’t disembark until 10 p.m. the next day, and he was one of the lucky ones. It took nine days before every Canadian was standing on English soil.

On Oct. 16, Parker arrived on Salisbury Plain, where the Canadian troops were assembled and trained. For several weeks after that, the men of the 7th went through drills, getting ready for the day when they would finally see action on the continent. They lived in “tents with no floor boards and outside and all around a sea of mud,” according to T.V. Scudamore’s A Short History of the 7th Battalion C.E.F.

From time to time, they enjoyed a break in the routine. One came on Wednesday, Nov. 4, when they were inspected by King George and Queen Mary at Busterd.

Parker got leave to spend part of the festive season with his mother and some of his siblings near London.

“I most certainly had a merry Christmas with all my brothers and sisters, Mother and Aunt Milly,” he wrote in a letter to his eldest daughter, Florence. “I hope you all enjoyed the Christmas tree; did you have one at home and another downtown?”

In his letter, Parker expressed hope that the war would end soon, so he could return to his family.

“God only knows what is in store for me,” he said. “May He grant, for all your sakes, that the war may come to a speedy end, and that we may all be permitted to spend next Christmas together.”

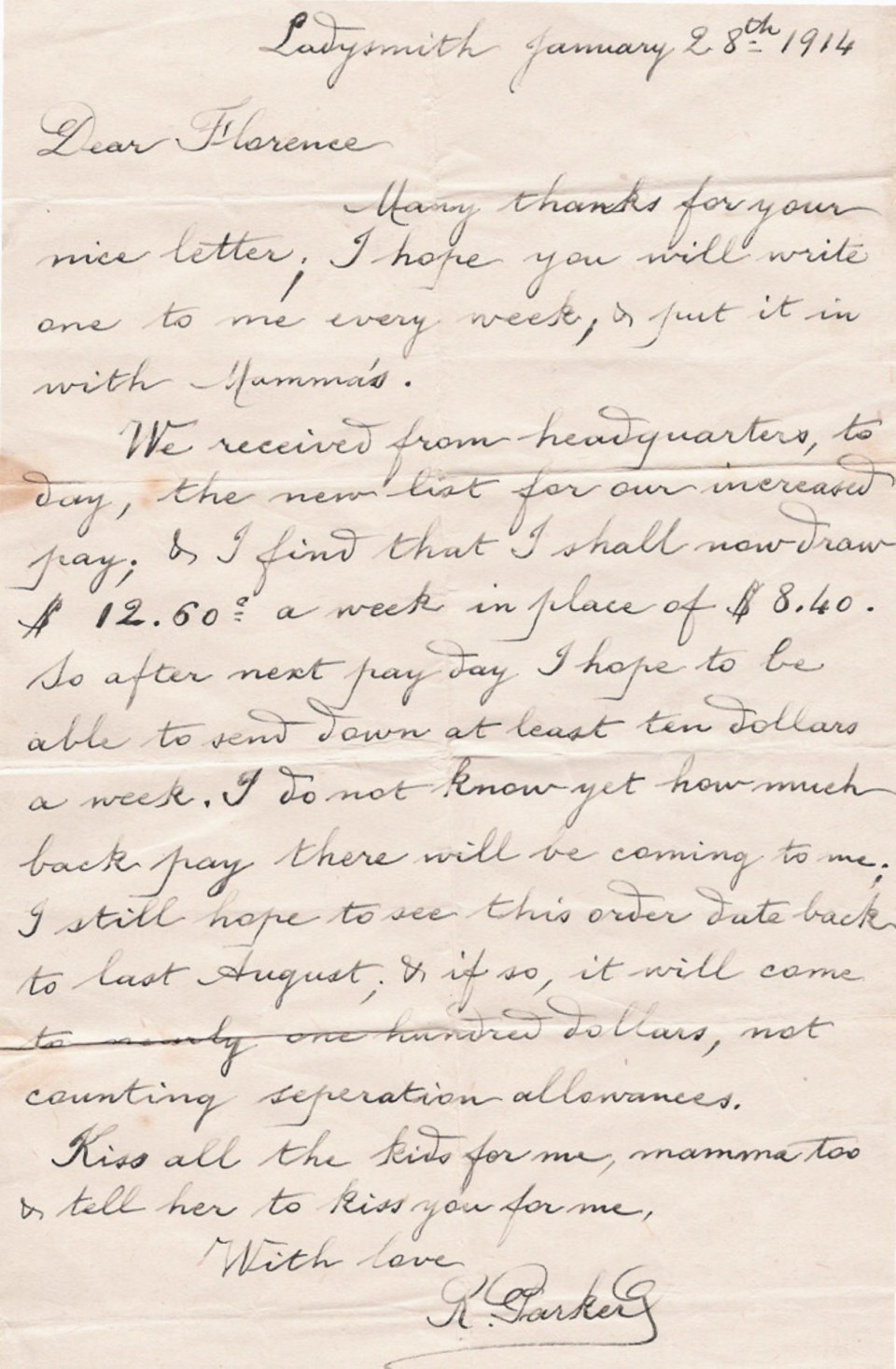

Parker wrote to Florence again a few weeks later. In that letter, he said that he had received an increase in pay, so he would be able to send at least $10 home every week. “I still hope to see this order date back to last August,” he said. “If so, it will come to nearly one hundred dollars.”

The family was not that lucky. Parker’s file at the national archives in Ottawa shows that the raise was effective Dec. 24, and worse, was for only half the amount that he told Florence.

Parker’s feelings about his family came through in the words he wrote to his daughter. “Many thanks for your nice letter; I hope you will write one to me every week,” he said. He closed with these instructions to Florence: “Kiss all the kids for me, mamma too, and tell her to kiss you for me.”

In February 1915, Parker was transferred to the infantry base depot in Tidworth, Wiltshire. As a result, he stayed behind on Feb. 11, when the rest of the 7th sailed from Avonmouth, near Bristol, to St. Nazaire, near Nantes on the west coast of France. It made for a long voyage — almost 39 hours — but it was important to avoid the German ships that were cruising the English Channel. To make matters worse, a heavy gale meant the troops could not disembark for 48 hours after arriving at St. Nazaire.

By the time the men of the 7th went to war, the Germans and the Allies had reached a stalemate close to the border between western Belgium and northern France. Despite horrendous losses of men, neither side could make headway, and the front barely budged for four years.

From St. Nazaire, the soldiers took the train most of the way to the battle zone. They finally arrived 11 days after leaving their camp in England.

After a few days of training in the trenches they were ready for action — and found it quickly enough. On Feb. 26, the 7th reported its first two casualties, including Lt. Herbert Beaumont Boggs, a 22-year-old law student from Victoria who had been a member of the 88th Fusiliers. Boggs, the son of a prominent real estate and insurance agent, is buried in the churchyard in Ploegsteert, Belgium.

“For the first time since the war started has the shadow of it fallen on Victoria,” the Colonist reported.

In late April, the men of the 7th experienced some of the worst that the Great War had to offer. They fought in the first Battle of Ypres (today, it’s Ieper), and witnessed the rolling clouds of poison gas unleashed by their German foes. The Canadians discovered quickly enough that their Ross rifles were prone to jamming. Many of them grabbed Lee-Enfields from their fallen British counterparts, and tossed the useless Rosses into the muck.

About 2,000 Canadians died in the Ypres battle, mainly because of poison gas. The Brooding Soldier monument at Vancouver Corner, northeast of the Belgian city, pays tribute to their sacrifice.

After Ypres, the manpower of the 7th was seriously depleted, and reinforcements were needed. Robert Parker was one of the men who came to the rescue. After a brief transfer to Shorncliffe, Kent, Parker was transferred back to the 7th “in the field” on April 30.

The records in his personnel file aren’t precise, and neither are the diaries maintained by the 7th. It’s likely, though, that he reached his battalion with a group of other reinforcements from England on May 7 — the same day that a German torpedo caused the Lusitania to sink, killing 1,198 people.

On May 7, the men of the 7th were in Bailleul, France, next to the Belgian border. Over the next few days, they marched south through French farmland toward the city of Bethune, stopping at villages such as Locon and Essars.

After a few days out of range of the German artillery, the 7th was pressed back into the battle at the village of Festubert, just east of Bethune. May 24 was by far the worst day of fighting, with 184 men of the 7th killed or wounded.

Robert Parker was one of the casualties at Festubert. He was lucky, at first — when the bullets ripped into his chest and thighs, they didn’t kill him. He was taken to a dressing station close to the battlefield, then moved by train to Wimereux, on the French coast about 100 kilometres from the front. The Rawal Pindi British hospital was there, ready to stabilize injured men so they could be shipped back to England for further treatment as quickly as possible.

But Parker’s wounds were too serious, and he couldn’t make the trip to England. His condition deteriorated. On May 31, he died, at the age of 39 years and five months. He was buried the next day in the military section of the Wimereux Communal Cemetery, on a hill at the north end of town.

The news reached Victoria a couple of days later, and Christine and her seven children had to accept the fact that Robert, their loving husband and father, would never be coming home.

Her two eldest daughters helped Christine pay the bills by getting jobs. She also received a government pension given to dependants of soldiers.

As she adjusted to her new life as a widow with seven children, Christine surely drew inspiration from her own mother, Mary Ann Newberry. The Newberrys had arrived on the Prairies in August 1892, and the following March, with most of the homesteading work yet to be done, Mary Ann’s husband William died. He was just 46. Mary Ann chose to stay on the homestead with her eight children, who ranged in age from five to 22. Eventually, with their help, she was able to complete the stringent homesteading requirements, and gained full ownership of the land.

Mary Ann Newberry died in Victoria in 1916, just 10 months after Robert’s death, but Christine still had brothers and sisters living in the city who could lend a hand when needed. Her brothers included Albert Newberry, who owned an antiques shop on Fort Street for many years, and John Newberry, a bookbinder in the government printing department.

Christine’s sister Florence Newberry worked for the Turner and Beeton overalls factory on Wharf Street for three decades, and helped Christine’s daughters Florence and Bessie get jobs there. Bessie found more than a job — she married the boss, David Weir, and moved to the southern United States.

Eventually, thanks to that pension from Ottawa, Christine and the children got to live in the house that Robert had promised to build when he returned from Europe.

“When he was killed, my mother hired someone to build the house. They used the same plans that my father had worked on,” Gladys George said in that 2005 interview. The three-bedroom house at 3119 Rose, next to the tracks of the old Victoria and Sidney Railway, cost Christine $1,200.

Christine stayed in the home as long as she could, even after all of her children had married and moved away. She outlasted the original name of the street; Rose became Alder in 1940. Finally, in 1952, when she could no longer live on her own, she sold the house. After that, she spent six months at a time with each of her daughters who were still in Victoria.

Christine died in November 1961 at 85, and was buried in Royal Oak Burial Park in Saanich.

She was predeceased by her daughter Bessie, who had moved to Long Beach, California. The other children died after their mother: Lillian in 1976 in Vancouver, followed by Frederick in 1984 in Clearbrook, and Florence in 1994 in Bellingham, Washington. Maude died in Vancouver in 2000 and Robert died the following year in Victoria. Gladys was 98 when she died in 2011, 94 years after her father’s death.

She said in 2005 that when her father marched off to war, she was too young to understand what was going on.

“I don’t remember him at all,” she said.

She did remember, though, that her mother never had the slightest interest in finding another man to replace her beloved Robert.

“After he died, she never even dated,” George said.

On May 31, 1915, the day Robert Parker died, the federal government announced that 999 Canadians had been killed in the war so far. Another 4,123 were wounded, and 1,314 were missing. There was no question the numbers would continue to rise, because every day the local newspapers were reporting more deaths — and repeating the call for volunteers to replace the casualties.

For much of the First World War, the two sides hammered away at each other with no real gains or losses in terms of real estate — but with a tremendous loss of life. By Armistice Day on Nov. 11, 1918, about 66,500 Canadians had died. Roughly one soldier of every four who served at the front died. And by comparison, that 66,500 is 22,000 more than we lost in the Second World War.

Most of these Canadians killed in the Great War are buried in the many war cemeteries that dot the landscape of western Belgium and northern France, near the city of Lille. From some spots, it’s possible to see two or three cemeteries with the distinctive Commonwealth War Graves crosses, similar to the ones at Veteran’s Cemetery in Esquimalt and the Royal Oak Burial Park in Saanich.

Robert Parker isn’t the only soldier from Victoria buried in Wimereux Communal Cemetery. In 1916 and 1917, it also became the final resting spot for at least three others from Vancouver Island: John Victor Bishop, Harold Brown and Charles Hugh Pearson Lipscomb.

Every year, hundreds of Canadians make a pilgrimage to the Wimereux cemetery, drawn not by the soldiers such as Parker, Lipscomb and the rest, but by a doctor who wrote poetry.

Like Parker, John McCrae left Canada in the first contingent, on Oct. 3, 1914. He also was posted to Salisbury Plain. But while Parker stayed in England to train new arrivals, McCrae was shipped out, and saw firsthand the horrors of the first Battle of Ypres.

A plaque next to the Essex Farm cemetery just north of Ypres marks the spot where McCrae wrote In Flanders Fields after a friend, Alexis Helmer, was killed by a shell on May 2, 1915. On the same day, Parker was on his way from England to the front.

McCrae was briefly in Festubert, too, but it was after the fighting there had stopped, so he wouldn’t have been at the dressing station when doctors were scrambling to save Parker’s life. On June 1, the day Parker was buried, McCrae was assigned to a British hospital in Boulogne-sur-Mer, about 10 kilometres south of Wimereux. He stayed in that area, far from the front, until he died of pneumonia in January 1918.

McCrae was buried with other officers close to the Cross of Sacrifice in the Wimereux cemetery. His grave is about 10 metres north of Robert Parker’s.

A total of 2,847 Commonwealth war graves are in Wimereux Communal Cemetery. McCrae’s grave is the easiest one to find, thanks to all of the poppies and Canadian flags that are left next to the stone every year.

The other 2,846 men and women were just as willing as McCrae to put their lives on the line for King and country. They, too, “lived, felt dawn … loved, and were loved,” to borrow McCrae’s words. While McCrae gets all the attention, the other 2,846 paid the same price.

And they were heroes, too. Heroes such as Robert Parker, who had a wife, seven children, a career, big plans for the future — and above all else, a commitment to serve his country.

Lest we forget.

Canadian sources used in this feature included interviews, the Canadian Expeditionary Force personnel files and the homestead records at Library and Archives Canada, military diaries, military histories, back issues of the Victoria Daily Times and the Daily Colonist, historic Victoria directories on the Vancouver Public Library website, the vital statistics index and images on the B.C. Archives website and Canadian census records. Sources in France included more interviews, civil registration files at the archives in Caen, and visits to the battlefields near Festubert as well as the Wimereux Communal Cemetery.

Dave Obee is editor and publisher of the Times Colonist