Neil McClelland is a person who likes to paint. I visited him in a gallery full of his painted panels, and he is also a sessional instructor at University of Victoria’s Fine Arts Department, where he teaches the “foundations” course. He also teaches at the Vancouver Island School of Art, offering introductory drawing, and courses in advanced painting.

Neil McClelland is a person who likes to paint. I visited him in a gallery full of his painted panels, and he is also a sessional instructor at University of Victoria’s Fine Arts Department, where he teaches the “foundations” course. He also teaches at the Vancouver Island School of Art, offering introductory drawing, and courses in advanced painting.

“Student-centred,” he says of his approach. “I was a high-school band teacher at one point, in a past life.”

McClelland grew up on a little farm in the Gatineau Hills, in Quebec across from Ottawa. After high school, he taught for 10 years, played in a band and studied art.

“Painting started to become the passion,” he told me. That led to a stay in Edmonton for 10 years, building a career.

“Edmonton is very rich in visual-arts culture, lots of different things,” he recalled. “The old-guard Abstract Expressionists are still being appreciated, and there is a lot of new representational art cropping up here and there around the city.”

McClelland himself has always been a representational artist.

“I admire abstract, but I don’t think it’s the logical conclusion of where painting should go. We have the privilege to pick and choose what we connect with.” He connects with Van Eyck, Velasquez and Peter Doig.

So what brought him to Victoria?

“First of all, it was the weather,” he said with a smile.

With his wife, he moved here five years ago, and enrolled in the master of fine arts program at UVic. Paul Walde was chairman of the department, and Robert Youds and Sandra Meigs were on his committee. McClelland also enjoyed the camaraderie of his 10 fellow MFA students. In the next studio was Jeroen Witvliet, who has become a good friend. In fact, the two are exhibiting together at the Comox Valley Art Gallery in Courtenay (until Feb. 25).

“When Jeroen and I got into the program in 2012, no one had used the sink to wash brushes for a couple of years,” McClelland remarked. “Nobody was washing brushes. We were both were strongly rooted in painting.” These days, painting has come back strongly at the university.

So what’s with the palm trees in his paintings?

“I see them as symbolic of the idea of pursing happiness.” They are symbols of utopian ideals, paradise on earth.

“The overarching theme of this show is the dystopian/utopian split, where everyone is looking for how to make a perfect society — and how it fails.”

Some believe technology will bring us to a place of perfect human happiness. McClelland made reference to William Morris’s book, News from Nowhere.

“We have to go back to Eden, get rid of all this stuff and go back to nature,” is how he summarized it. The opposing tendency is found in Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, in which the technological wonders of modernism will create the perfect city.

“I see this all the time now,” McClelland noted, “the twin impulses.”

The first painting in his suite shows a tourist walking on a sun-drenched beach, with the sea turtles. Slowly you realize that the sunny sky is just a projection on a screen — it’s all happening in a dome.

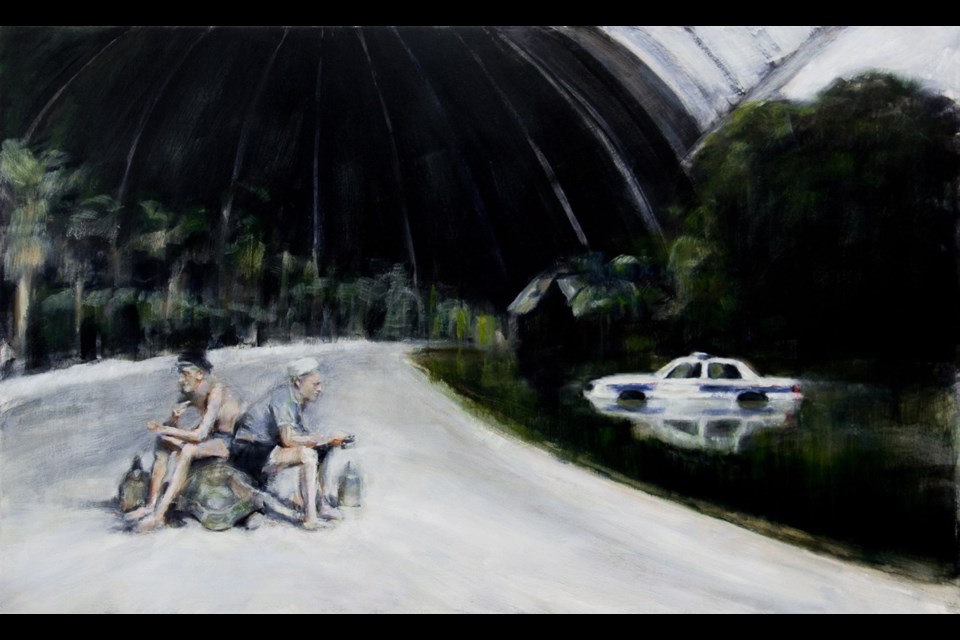

“We worship nature, but it’s constructed and commodified. You probably have to pay admission,” he chuckled. The next painting shows another tropical beach with a police car offshore, in water up to its hubcaps.

McClelland asked me: “What does that mean to you?” Always the teacher …

The juxtaposing and layering of images goes on, right from the start. On his computer, he rearranges images that he has “taken or found or distorted or made transparent or erased.” This provides him with a jumping-off point for the painting. After that, the materials take over.

“It’s almost like a collaboration with the materials,” he says. This artist loves to work between control and letting loose.

I point out a drip running past the hoof of a rearing horse — or a statue of a horse. How loose does he get?

“Depends on how much oil content,” he told me. “More solvent, the faster it runs. It could take a whole day for a drip to happen.”

In the paintings, McClelland enjoys establishing an atmosphere redolent with the tension between utopian and dystopian. Oppressive dark shadows are balanced by the play of light on a calm figure surrounded by flowers. McClelland likes to play with these contradictions.

In his Palm Springs painting, a woman in a pool looks out into her backyard, where the earth is cracking open.

“It’s kind of an open narrative,” he mused. “It takes on different connotations depending on when it is viewed.”

Throughout, McClelland uses a very limited palette, explaining that “all these paintings are made from maybe four tubes of paint. I tend to mix every colour from primaries.” They are ultramarine blue, hansa yellow, alizarin crimson and flake white — he still depends on lead white.

“Oh, yeah,” he added, “and a little burnt sienna.”

Black?

“No. Black tends to murder colour in most circumstances. I will use black in portraiture, but not in this. Even without black, I take great pains to maximize intensity: the value and the drama.”

Anything else?

“Make sure that the neutrals are alive,” he advised. “I want them to be beautiful.”

Everything Is Being Perfected, Neil McClelland, Deluge Contemporary Art, 636 Yates St., deluge.ws, until March 4.