Imagine this: It’s 1:59 p.m. on a wet Thursday in January. Three straight days of heavy rain have dropped up to 300 millimetres on British Columbia’s coastline. In the alpine, temperatures are climbing, sending meltwater downriver.

All that water is triggering landslides across the region. Vancouver’s North Shore and Chilliwack Valley are hit particularly hard. Water levels rise in the Squamish, Seymour, Chilliwack and Coquihalla rivers. Dikes are under siege.

In the province’s capital, too much rain has broken water mains and flooded basements. Many farms are under water. The Malahat highway is covered in rockfalls and volunteers are stacking sandbags as rivers flood the Cowichan Valley.

On the road, many routes are blocked or diverted so drivers can avoid flooding. Parents are picking up their children at school early, but in downtown cores, it’s business as usual after a break for the holidays.

The minute hand slips to 2 p.m.

“For many, the earthquake is heard before it is felt,” imagines the B.C. government in its latest disaster plan, updated for the first time in seven years as part of its Provincial Earthquake Immediate Response Strategy (PEIRS).

“The low, rumbling sound is similar to that of a freight train, immediately followed by 10-20 seconds of violent shaking that knocks people located closest to the epicentre from their feet — except for those who remember to ‘drop, cover, and hold on.’”

In one scenario, provincial emergency planners modelled what would happen in the event a magnitude 7 earthquake struck the Metro Vancouver region; in another, Greater Victoria is hit with a magnitude 7.3 quake.

In both cases, the destruction is like nothing the region has seen in modern history.

Roads crack as ruptures open up in the ground. Unsecured objects fly through the air.

In low-lying places like Richmond, liquefaction is likely. That's where the shaking ground forces water up through the soil, sand and stones, instantly turning once solid terrain into a semi-liquid stew. Anything that land once supported gives way, sinking into the morass.

Rockfalls cut off transportation routes. Dikes fail. Fires spring up at the site of ruptured gas and electric lines.

“A small number of buildings collapse, many shift and crack, and others are destroyed by fire,” says the PEIRS report.

On the ground, the government document describes urban landscapes strewn in broken glass and roadways choked in the debris of collapsed buildings.

Some of the worst tragedies are made magnified by panicked choices.

“Many of those who try to run outside suffer extreme injury or death from falling and flying objects and thousands are trapped or injured,” the report says.

A devastating human and financial toll

Planning for a collision between climate-driven flooding and a large earthquake leads to some sobering numbers.

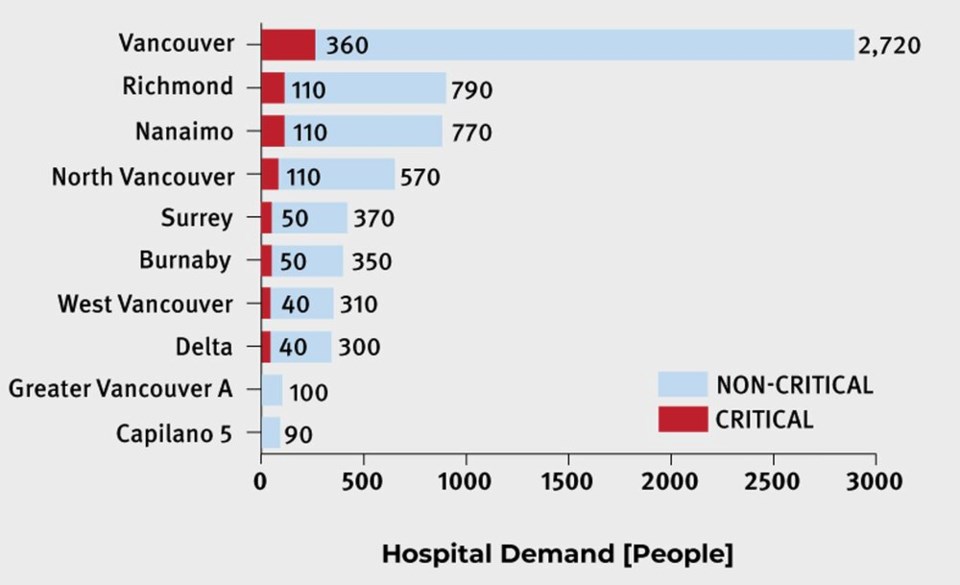

If the earthquake were centred in Vancouver, the province projects 2,000 people would be killed, with 1,000 critically injured. Another 6,500 are expected to require hospitalization and 21,000 more would need help from a paramedic or someone who can provide first aid.

Across the province, the combined atmospheric river and earthquake would make over 16,000 buildings uninhabitable and push 70,000 families and individuals from their homes.

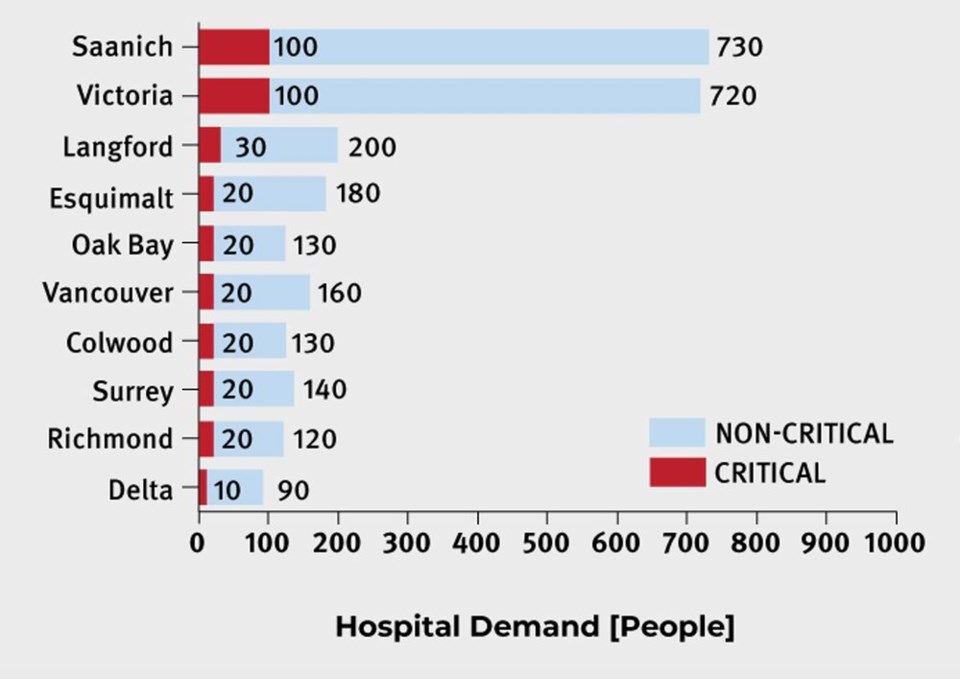

An epicentre in Victoria, meanwhile, would lead to 1,000 deaths, 3,700 hospitalizations, and another 10,000 injured. Roughly 43,000 households would be displaced.

In both scenarios, first responders and hospitals would be quickly overwhelmed, and many would likely face deteriorating health as their injuries go untreated.

None of the casualty estimates consider the effects of underlying medical conditions or secondary hazards like “vehicle accidents, falls, explosions, fires, landslides, washouts, tsunamis, or psychological impacts,” notes the report.

Anyone in the backcountry, in the North Shore mountains or beyond, would likely struggle to escape as search and rescue crews would be overwhelmed or incapacitated.

Structural damage would be everywhere. One to 1.7 million people would find their homes damaged from the shaking and its aftermath.

Economic activity would screech to a halt. For every day the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority is out of operation, it would lose $647 million in cargo — something that “would have cascading effects across the country.”

Economic losses range from $30 billion if Metro Vancouver were the site of the earthquake’s epicentre, to $20 billion if Victoria were hit hardest.

The report notes that overall economic fallout would likely be much higher, with other studies noting Vancouver alone could face a potential $10 billion in damage.

Aftershocks would 'likely continue for months'

The initial devastating 20 seconds of shaking wouldn’t end there.

For shallow earthquakes in the magnitude 7 range, strong shaking is expected to cause most of the damage, though landslides, liquefaction, flooding, fires and the outbreak of disease would make things worse.

Aftershocks beyond magnitude six “would likely continue for months,” causing further mayhem and psychological damage to already traumatized residents.

“There is a small chance that an 'aftershock' could be larger than the initial event,” write the authors of the government report.

In the meantime, small businesses would be severely impacted by supply chain disruptions and bank services — including ATMs — could be left largely unavailable, the report notes.

Basic services like water, electricity and gas would likely be cut or disrupted “for many months.”

With cell networks overloaded, text messaging would probably be one of the easiest ways to communicate. Even radio communication could face congestion as non-sanctioned operators and emergency services compete for airwaves.

“There may be increased reliance on backup communication methods, such as satellite phones and amateur radio services,” notes the report.

In the city, congested shelters and a lack of waste disposal could lead to outbreaks of disease. On the other hand, isolated communities with one road or bridge in and out of town could be entirely cut off for long periods of time.

Government responds, military launches CONPLAN PANORAMA

After a catastrophic earthquake, the B.C. government is expected to shift all its priorities to disaster response, notes the document.

The Office of the Premier and cabinet would direct the Provincial Emergency Coordination Centre in Victoria, which in turn, would pass information to regional and local emergency coordination centres, municipalities and First Nations.

In the worst-case scenario, the province may set up a Catastrophic Emergency Response and Recovery Centre to provide unified command and share information with the press and public.

Emergency Management BC (EMBC) would activate the province's earthquake response strategy, recommend government declare a state of provincial emergency, and contact Public Safety Canada for federal assistance.

The federal government would almost certainly activate CONPLAN PANORAMA, a contingency plan for the Canadian Armed Forces in the event of a catastrophic earthquake on the coast of B.C. That would mean deploying soldiers to staging areas across Vancouver Island, the Lower Mainland or the Southern Interior.

The military would be tasked with supporting communities directly hit by the earthquake or cut off from its effects. In the same way military units were flown into parts of B.C. during last year's floods, the armed forces may also be deployed to Indigenous communities, but only after consultation with their leadership.

Earthquake early warning system could soften the blow

The scenario does not consider the use of an earthquake early warning system — one that is already partially deployed and expected to become operational across parts of B.C. in the coming years.

Once up and running, that system could give people a warning “on the order of minutes,” allowing many to escape collapsing buildings and buckling tunnels and bridges.

With warning, SkyTrains could be halted, surgeons would have a chance to stabilize patients, and firefighters would open fire hall doors, giving them a head start.

At the same time, the provincial report notes, the modelled scenario makes a lot of assumptions.

In the event of a real earthquake, “it may take hours or even days to collect situational awareness equivalent to what is presented here.”

A response in progress

The report and its hypothetical scenarios come the same week millions of B.C. residents had the chance to practice their own reaction to an earthquake (the annual Great British Columbia Shake Out encourages people to practice how to drop, cover and hold.)

And this February, municipal governments across B.C. will join their B.C. and federal counterparts to hold a large-scale earthquake dry-run dubbed Exercise Coastal Response 2023. Working with First Nations, it's meant to “validate elements of the new strategy and reinforce the importance of cross-jurisdictional partnerships in emergency situations,” according to a recent press release from the province.

As part of its plan to seismically upgrade infrastructure like bridges and highways, the Ministry of Transportation has earmarked $5 million a year.

School seismic retrofits, on the other hand, still have a long way to go, despite $2 billion in approved and promised funding.

As of Sept. 22, 204 B.C. schools had been seismically upgraded, while 22 were under construction. Another 268 schools across the province have yet to receive retrofits and remain vulnerable to a catastrophic earthquake.