With calls to remove statues of controversial figures such as Sir John A. Macdonald, the University of Victoria is putting on a series of lectures about the historical characters in the news. Four historians are presenting brief “warts and all” biographies of four historical figures in the news: John A. Macdonald, Joseph W. Trutch, Matthew Baillie Begbie and James Douglas and putting them in their historical context to help inform public discussion. Each talk will be followed by a discussion on such questions as “how should we remember these characters and their contexts?” and/or “to commemorate or not commemorate?” John Adams will speak about Sir James Douglas on Monday. All talks will take place in council chambers, City Hall, 1 Centennial Square, Victoria, 7-8:30 p.m.

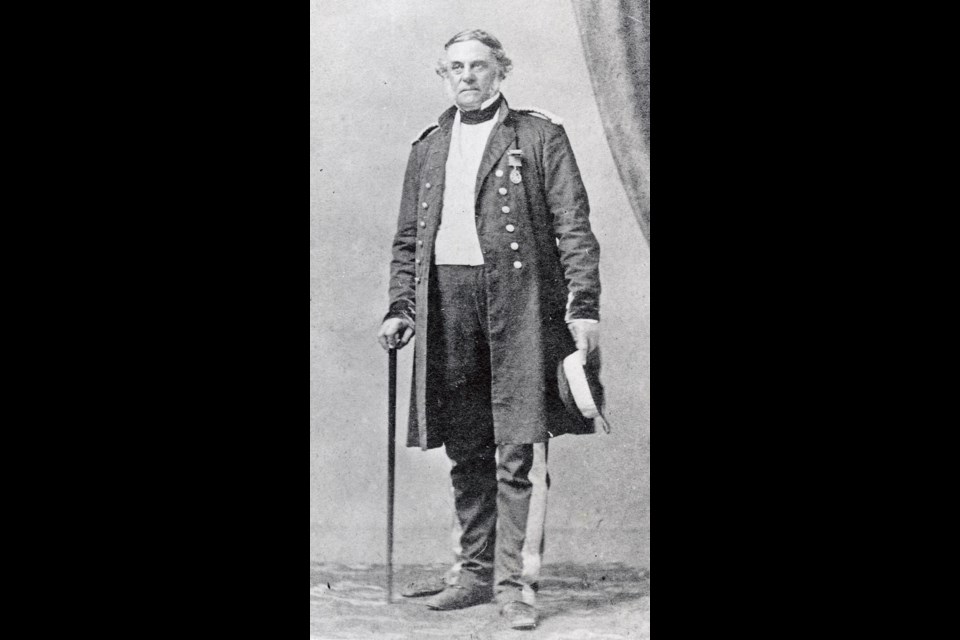

James Douglas was born in controversy and was immersed in it throughout his life. He served as chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Victoria (1849-1858) and was also governor of the separate colonies of Vancouver Island (1851-1864) and British Columbia (1858-1864). He was a “great man” in the traditional sense historians have used the term, but was also at the centre of incidents involving First Nations that cast him in a different light.

Ironically, the current criticism of Douglas’s dealings with Indigenous issues was given scant attention during his day, but his many detractors found no shortage of other things to dwell on.

Illegitimacy and mixed marriages today do not have the same stigma they did during the 19th century. Douglas was born out of wedlock to a part-black woman from Barbados and a Scottish father, the sort of detail many families kept quiet in days gone by. Some contemporaries referred to him as a “mulatto,” and most people who met him commented on his dark complexion. His origins probably influenced his decision not to settle in Oregon, where laws banning blacks and mulattos from residing started in the 1840s.

For many years, historians were puzzled about Douglas’s origins, until the 1970s when Charlotte Girard, a retired history professor from the University of Victoria, went to Guyana (formerly British Guiana), where Douglas was born in 1803, and found the documentation that cleared up the confusion. Previously, prudish gossips had plenty to speculate about concerning Douglas’s lineage, yet they never openly criticized him for it. One of his chief detractors, Amor de Cosmos, founding editor of the Daily British Colonist, rarely had a kind word to say about Douglas, but never publicly referred to his racial origins.

On the other hand, hostile observers were brutal in their portrayal of Douglas’s wife, Amelia. She was Métis, something that is now a source of pride among many in Canada. One who thought differently was Lt. Edmund Hope Verney, commander of a Royal Navy gunboat at Esquimalt in the early 1860s, who wrote to his father (a member of Parliament in England) that Amelia was “utterly ignorant,” noting that “she jabbers French or English or Indian.”

In 1854, Annie Deans, a resident at Craigflower Farm, wrote that Douglas had spent “his whole life among the North American Indians and has got one of them for a wife, so can it be expected that he can know anything at all about governing one of England’s last colonies in North America.”

Douglas had a short temper, got into fights as a young man and, on at least one occasion, was involved in the murder of a First Nations man. Think of the fodder these revelations would provide for a scandalmonger trolling for dirt about a politician these days.

The charge of murder would be the most serious, but in the 1820s when it happened at Fort St. James, it was seen in a different light. When Douglas learned that Zulth-nolly, a Dakelh man alleged to have murdered a Hudson’s Bay Company employee, was hiding in the house of Chief Kwah at the nearby Dakelh village, Douglas and other men broke in while the chief was absent and killed the culprit.

Chief Kwah was enraged when he found out and went to avenge the infraction. But it was the trespass, not the murder, that was his biggest complaint. In one version of a famous scene, Kwah’s nephew overpowered Douglas and was about to plunge a dagger into his heart when his uncle called him off. One of the reasons was that Amelia Douglas offered sufficient trade goods to compensate for her husband’s misdemeanour.

Douglas was autocratic and considered anti-democratic in his day. To many settlers who arrived in the colony of Vancouver Island in the 1850s, these were the biggest controversies of all. A petition protesting his high-handedness was circulated, and Robert Staines, the Anglican chaplain at Fort Victoria, was chosen to carry it to England. Staines did not succeed because his ship sank off Cape Flattery.

In spite of the fact the Colonial Office had asked him to hold elections for an assembly — albeit one with limited powers — Douglas held off implementing this until 1856, when he was ordered to do so. The fight for responsible government was continued by de Cosmos in 1858, and was the source of much of de Cosmos’s open animosity to Douglas.

Douglas was self-serving and practised nepotism to a degree considered phenomenal, even in his day. His opponents dubbed this the “family-company compact.” Douglas simultaneously filled the positions of chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company and governor of Vancouver Island, a clear conflict of interest.

While in these roles, he bought land in the choicest locations, built the colonial administration buildings (the so-called “Birdcages”) next to his own house, had the James Bay Bridge built to connect downtown Victoria to his property, created a subdivision at the end of the bridge, then sold the lots for a big profit. He made Beacon Hill Park a land reserve between his home (now the site of the Royal B.C. Museum) and his large private estate in Fairfield, then had the audacity to purchase part of the park, near present-day Cook Street Village, to add to his own holdings.

He made sure close family members filled almost every influential position in the colony. Today, public figures would probably end up in jail if they did what Douglas did with impunity.

Douglas shamelessly favoured Victoria over New Westminster, the capital of the mainland colony, gaining him the enmity of New Westminster residents. Declaring Victoria a free port to ensure that all imports passed through that city is just one blatant example.

In recent years, Douglas has been criticized for not negotiating treaties with First Nations, except around Greater Victoria, Nanaimo and Port Hardy. He was instructed to sign treaties elsewhere and even had money budgeted for this, but the Assembly did not approve its expenditure. Though he did make generous allocations for reserves in the Interior — too generous according to some detractors — he did not ensure the boundaries were inviolable.

After Douglas retired in 1864, Joseph Trutch and others reduced the size of reserves until they were fractions of the originals. Some suggest Douglas was overwhelmed by gold-rush-era administration and so had little time to deal with treaties or to register the reserves. Others suggest it was a deliberate ploy on his part to disregard aboriginal title to the land.

Another major controversy is the alleged genocide against Indigenous people during an epidemic of smallpox in 1862. When smallpox broke out in Victoria that year, First Nations visiting the city from the north were ordered to leave to minimize the risk of infection in the city. Smallpox was thus kept under control around Victoria, but spread at an alarming rate among the First Nations along the coast.

While the smallpox outbreak and forced dispersal of First Nations were real, there is little evidence that this was planned genocide.

Why would Douglas want to wipe out the aboriginal population? One reason might have been to open up their land for settlement by outsiders without having to resort to treaties or warfare. This certainly happened in some other places. Did it happen here? Douglas’s record of trying to protect Indigenous rights during the Fraser River gold rush in 1858 is one example that suggests he had an interest in safeguarding, not destroying, First Nations occupation of their land and waterways.

So, if you want to find controversy about James Douglas, take your pick from the above examples, or find something else from a long list of other possibilities. Retiring the name Mount Douglas and reverting to the Indigenous name PKOLS is a courtesy to local First Nations that has merit, regardless of any discussion over Douglas’s actions. But before we contemplate changing the name of Douglas Street and the Douglas Building or pulling down the two statues of Douglas at the Parliament Buildings, we should consider Douglas’s many good accomplishments that deserve commemorating.

He recognized Indigenous title to land, granted Indigenous people full legal standing before the courts and was committed to protecting a land base for them. He accomplished the remarkable feat of founding two colonies and maintaining the peace with precious few resources at his disposal, even when 30,000 American and other foreign miners descended on British Columbia.

John Adams is a local historian, lecturer and author who is well known around Victoria for the walking tours he conducts through his company Discover the Past. His biography of James Douglas is called Old Square Toes and His Lady: The Life of James and Amelia Douglas.