Last week, I suggested one of the key problems we face is that our critical challenges are long-term, but our thinking and decision-making is short term.

I noted the UN Secretary General, in a September 2021 speech to the General Assembly, said “global decision-making is fixed on immediate gain, ignoring the long-term consequences of decisions — or indecision.” And I stated we need a time horizon that extends beyond this financial year-end or this legislature’s term of office.

So I was very pleased to see Victoria Mayor Lisa Helps, in an interview in last Sunday’s Times Colonist, saying she sees her job as setting the city up for success 50 years down the line, and that “some of the policies that we’ve put in place and the actions we’ve taken … are leaving a good legacy for the next 50 years.”

The choice of 50 years is an interesting one, because one of the themes I will explore in my columns this year is that 2022 marks 50 years since the first UN Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm in June 1972.

In many ways, the intervening 50 years have been, if not yet quite a disaster, at least a very serious setback for the global environment. As someone who first got interested in environmental issues in the late 1960s, I saw that UN conference as heralding a turning point, a new beginning.

After all, the conference book was titled Only One Earth, the Club of Rome published a report on The Limits to Growth, and The Ecologist published Blueprint for Survival, which, among other things, called for the creation of ecological political parties.

Already, Rachel Carson had shown us the ravages of the chemical industry in her landmark 1962 book Silent Spring, Paul and Anne Ehrlich had discussed the challenges of population growth in their 1968 book The Population Bomb, and Francis Moore Lappé had discussed the importance of shifting to a low-meat Diet for a Small Planet in her 1971 book of that name.

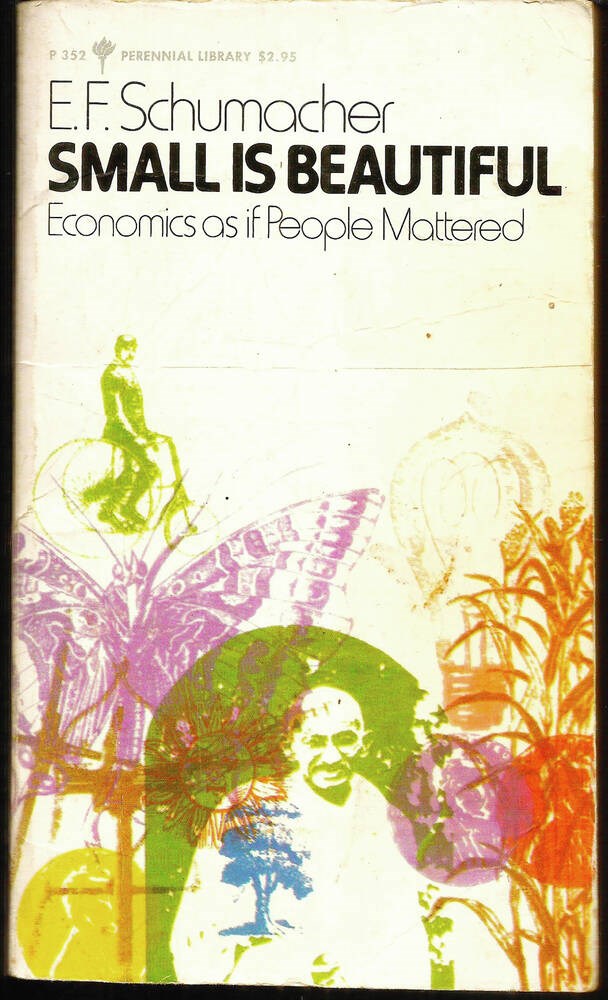

Within a year of the conference, the Buddhist economist EF Schumacher had described a system of “economics as if people mattered,” the subtitle of his 1973 book Small is Beautiful. In that same year the first two ecological parties were begun; the People Party in the U.K. and the Values party in New Zealand, both to become Green parties following the establishment of the German Greens in 1980.

I genuinely thought that in the coming years, we would begin the transition to what the Science Council of Canada, in a 1977 report (back in the days when we actually had a Science Council), called a Conserver Society, what others called sustainable societies or communities.

But it was not to be, although small initiatives in many places did try to create more sustainable communities, and some positive changes have occurred.

Every decade, we thought we would see the shift start, but it never did. The 1987 report of the World Commission on Environment and Development proposed the strategy of sustainable development, and Lester Brown, founder of the Worldwatch Institute, dubbed the 1990s the “turn-around decade.”

But we did not turn.

Fifty years after the Stockholm conference, the global population is two times larger, while the world GDP per person is 2.5 times larger, so in roughly 50 years, our total impact has increased five-fold, while our technologies are more powerful, widespread and pervasive than ever. As a result, we are crossing planetary boundaries, overheating the planet, exceeding the Earth’s biocapacity and decimating the biosphere.

For the sake of future generations, not to mention other species, we desperately need to make sure that the next 50 years do not repeat the past 50 years of delay, denial and obfuscation by powerful industries, fossil fuel-rich countries and other economic interests wedded to a neo-liberal “consumer society” agenda.

I concluded last week that what I really want for 2022 is wider public discussion about the reality of the existential challenge of the multiple human-induced ecological crises that are conveniently referred to as the Anthropocene, and how we should respond here in the Greater Victoria region.

I intend to use my column this year to pursue that discussion.

Dr. Trevor Hancock is a retired professor and senior scholar at the University of Victoria’s School of Public Health and Social Policy.