This is my final column about Tyler, the fictional young offender whose story was told in a 2016 Public Safety Canada report. Last week, I discussed the value of support in the first three years of life to help parents create secure attachment, as well as interventions to reduce the occurrence or impact of adverse childhood events. The latter includes eliminating child poverty — which is always, of course, parental poverty.

Oddly, the PSC report did not include these early interventions, perhaps because they are for all children, while the interventions they reported on are aimed at children already having problems or involved with the justice system. But nonetheless, for the two interventions described here, the estimated net savings for Tyler were in excess of $1 million. (A third program described in the report might be less effective in Canada than the U.S., where it was developed, so it is not discussed here.)

The first program is SNAP — Stop Now and Plan, a program developed by the Child Development Institute in Toronto and now recognized internationally. SNAP works with troubled children ages six to 12 and their parents, and its goal is “to help children to stop and think before they act, and keep them in school and out of trouble.”

The PSC report notes a 2007 study found that “delinquency, major aggression and minor aggression decrease significantly after participation in SNAP,” at a cost of less than $7,000 per participant. SNAP itself reports: “Recent research indicates that 68 per cent of SNAP participants will not have a criminal record by age 19,” and that the return on investment is $7 for every dollar invested in the first year.

So you would think this program would be in place everywhere across Canada — and you would be wrong! SNAP’s website describes its plans to expand to 120 sites from the current situation — a mere 20 sites — of which only four are in B.C.: the Coquitlam and Nechako Lakes-Vanderhoof school districts and two small community agencies in Vanderhoof and Salmon Arm.

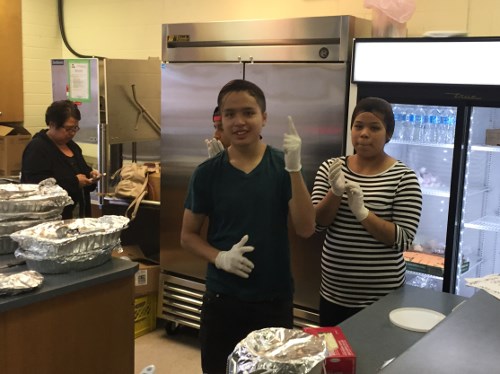

The second program is the Youth Inclusion Program (YIP), which was developed in 2000 in the U.K. It is a neighbourhood-based program that works with adolescents (ages 12 to 17) and young adults (18 to 24) and is supported through PSC’s National Crime Prevention Strategy. It aims to create “a safe place where youth can go to learn new skills, take part in activities with others, and receive educational support” in areas where “there is a strong need to reduce youth crime and antisocial behaviour.”

The YIP also works. Two Canadian evaluations between 2010 and 2016 showed that participants reduced their risky behaviours — in one case by 67 per cent — at an average cost of between $8,500 per participant. But again, there were only 13 sites in Canada, with three in B.C.: Agassiz-Harrison, Smithers and Salmon Arm.

It is important to understand that as with so much else in society, the worst-case stories are the tip of the iceberg, and do not represent the whole picture. For every Tyler, we can be sure that there are many others whose problems were not as obvious or severe, but who nonetheless were problematic. In fact, the chances are that their overall impact on society is greater, because while less costly individually, there are so many of them. The loss to society — not just economic loss, but loss of human potential and social well-being — is significant, and to a fair extent is preventable.

Any society that was truly caring and compassionate — and sensible — would realize that investing in creating the healthiest possible start for every single child in Canada would have huge health, social and economic benefits. So why don’t we do so — why is this not a national and provincial priority? Why is there not a Ministry of Healthy Child Development, instead of a hodgepodge of poorly funded programs across multiple ministries?

If we want to have fewer Tylers, we need to get very serious about this. Governments that fail to invest in a comprehensive healthy child-development strategy are guilty of wasting a huge amount of human and economic potential. They are also guilty of neglect every bit as much as parents who neglect their children.

Dr. Trevor Hancock is a retired professor and senior scholar at the University of Victoria’s School of Public Health and Social Policy.