B.C. spends more than $100 million a year providing anti-HIV drugs free to eligible patients, helping boost the uptake to 85 per cent of those with HIV on Vancouver Island.

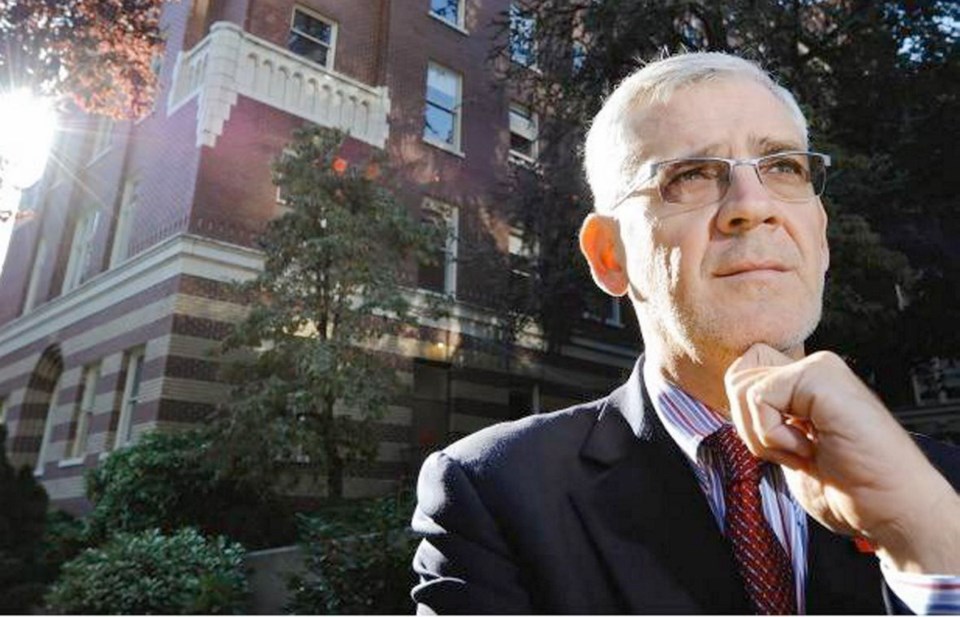

Only four years ago, just 56 per cent of B.C.’s HIV patients received highly active anti-retroviral treatment, which plays a major role in reducing transmission of the virus, said Dr. Julio Montaner, director of the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS.

HAART drugs, which Montaner helped pioneer, reduce the viral load in people with HIV to undetectable levels, he said.

“If your partner is HIV undetectable on treatment, you have a greater than 95 per cent chance of being protected,” even without use of a condom, he said. The truer estimate is probably much greater than 95 per cent, based on thousands of people studied for several years, he added.

HAART costs about $15,000 per patient, per year.

The fact that the Ministry of Health picks up the full tab for each person is “incredibly good,” said Katrina Jensen, executive director of AIDS Vancouver Island. Other provinces do not.

The B.C. policy means that AVI and other groups can concentrate on breaking barriers to treatment without worrying about the cost of the treatment itself, she said.

Barriers include outdated beliefs that treatment requires complicated drug cocktails and dozens of pills taken several times a day. The reality is that some HIV patients need to take only one pill per day, others several, Jensen said.

B.C. is the only province where new HIV cases are in significant decline, says the ministry, and provincewide uptake of HAART drugs has reached 73 per cent.

However, just being in treatment doesn’t necessarily mean a person is adhering to the HAART regime or indicate the level of viral suppression, noted Sophie Bannar-Martin, HIV/AIDS co-ordinator for Island Health.

In south Vancouver Island, about 70 per cent of people receiving HIV treatment have achieved suppression of the virus in their blood, Jensen said. People who receive support at Cool Aid Community Health and AVI have a much higher rate of viral load suppression — about 95 per cent, she said.

“If people are homeless or hungry or struggling with mental health or addiction, taking pills on a daily basis can be challenging,” she said. Making and remembering appointments in the first place is an even bigger challenge, she added.

AVI works with more than 200 people living with HIV in Victoria to help stabilize their lives to maximize the success of HAART, she said. That includes provision of hot meals five days a week, along with support services out of the Access Health Centre on Johnson Street.

“Now we need to focus on the reasons why people have trouble with adhering to it and how we can increase the support they need,” Jensen said.

Vancouver Island does not have support programs seven days a week, such as Vancouver’s MAT — Maximally Assisted Therapy Program — which supplies medications, food and social workers.

AVI is open five days a week and Cool Aid five and a half days.

“What would be great is to do a needs assessment with people living with HIV who are having trouble getting on or staying on treatment and then try and obtain funding for seven-day-a-week service,” Jensen said.

“That would be a goal for this year.”

It would be money well spent, Montaner said. “It can be done, it should be done and we should be re-examining it.”

Despite the rise in HAART uptake, there are gaps in HIV treatment, he said.

First Nations people and men under 35 having sex with men are not experiencing the same level of reduction in HIV/AIDS, he said. Aboriginal people suffer from social and economic impediments, and are more likely to live in isolated communities where they feel their privacy could be compromised in seeking diagnosis and treatment, he said. “Even when they access services, the challenge is to optimally benefit from the services.”

Because of persistent prejudices around homosexual behaviour, young men having sex with men often do not feel comfortable coming out, he said. “The youth need to be better supported as they come out sexually and start experimenting with sex.

“They are exposed to an inordinate risk, so greater supportive education is something that we need to look at very closely.”