TORONTO — Zippers. Garbage bags. Paint rollers. Some items are so ingrained in our lives we don’t stop to consider life without them — how we would do up a jacket, take out the trash or give a wall a fresh coat of paint?

But without the Canadians behind these inventions, all these tasks — and many more — would prove a little more difficult.

Without Joseph Leopold Coyle’s “Eureka” moment more than 100 years ago, for example, carrying eggs home from the grocery store might be a whole lot messier.

“There were ways of shipping eggs before Mr. Coyle, but the modern, paper container begins with him,” says Lorne Hammond, the curator of human history at the Royal B.C. Museum in Victoria.

Coyle is among Canada’s countless tinkerers, inventors, scientists and engineers whose creations have changed the modern world. But his tale is also a cautionary one at a time Canadian governments are trying to figure out how to foster innovation that will drive the 21st century economy. While his invention remains used to this day, it never earned him a big payout.

Many business leaders, academics and policy-makers say Canada must get better at converting the innovations and intellectual property that flow from its finest minds into successful global companies.

Canada has a proud history of innovation and has “truly punched above its weight,” says Greg Dick, director of educational research at the Perimeter Institute. The Waterloo, Ont., theoretical physics research hub is one of five organizations behind Innovation150, a year-long, cross-country tour designed to inspire youth to innovate.

Perimeter itself was launched in 2000 with funds from the founders of BlackBerry, the smartphone pioneer that grew into a global player, but later lost most of its market share to foreign competitors.

Dick rattles off a list of Canadian contributions to a wide variety of fields: time zones from Sir Sandford Fleming, dubbed the “Father of Standard Time;” basketball, courtesy of the imagination of Dr. James Naismith; more recently, a vaccine to fight the Ebola outbreak in West Africa that began in 2013, designed by scientists at Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg.

“The sunglasses for snow blindness? Invented by the Inuit in the Canadian Arctic,” he continues. “And, peanut butter? There’s a fun one. First patented by a Canadian. … We just really have done an incredible amount of contributing to society.”

That’s backed up by the number of patents the Canadian Intellectual Property Office has granted since 1869, when it (then known as Consumer and Corporate Affairs) awarded Canada’s first patent to William Hamilton for his eureka fluid meter.

In 1976, the federal agency granted the one millionth patent for “photodegradable polymer masterbatches” and, as of last year, surpassed 1.6 million approved patents with about 37,000 applications received annually over the past decade.

But in a sign of how much innovation is going on elsewhere, only about 13 per cent of those applications come from Canadians, according to Agnes Lajoie, assistant commissioner of patents at CIPO. The organization would like that number to move higher.

The office is working to raise awareness about the patent system among small- and medium-sized businesses in the country, focusing on high-growth sectors that are intellectual-property intensive, such as clean technology and aerospace, says Darlene Carreau, director general of CIPO’s business services branch.

“Canadians are very innovative,” she says.

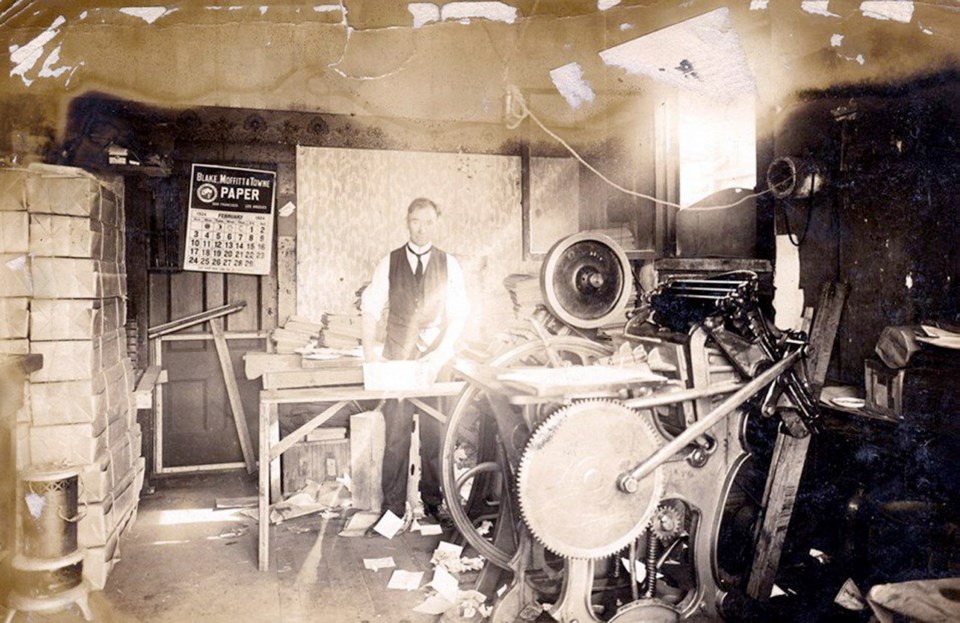

One of those early, little-known inventions came from Coyle, who secured a grade-school education before working his way up from cleaner and newspaper delivery boy to founding The Interior News in 1910 (it continues to publish today).

Back then, the paper’s office stood in what was known as Aldemere in British Columbia’s Bulkley Valley, near a hotel that was the spot of frequent fighting between the hotelier and a farmer, Gabriel Lacroix. The owner hated that his regular order of eggs often arrived as a mess of runny yolks.

One day, Coyle overheard this argument and that — as legend has it — was his a-ha moment. He set out to create a container to keep the eggs intact from coop to customer. In a 1917 patent application to CIPO, he described a “simple, inexpensive and safe” way to carry a dozen eggs at once in an egg box that suspended and supported each one without letting it touch the others. Coyle later obtained patents for several other countries as demand for his egg box grew.

The “venture is going to beat the band and getting bigger and bigger every day,” Coyle wrote in a letter to his former newsroom colleagues in the winter of 1919, according to an article the paper published that year. A year later, however, he admitted in another article that an obstacle stood in the way of expansion: the cost of production.

Coyle holed himself away for several weeks to fashion a machine that could manufacture his product less expensively and by the end of March 1920, it was operational.

The newspaperman-turned-inventor also received patents for an automobile lock that prevented a steering wheel from moving until the device was removed, a match safe that dispensed one match at a time and could trim the end of a cigar, and a cash till that could separate coins by amount and dispense them individually.

“He was just, sort of, an inventive soul,” says Kira Westby, the curator at the Bulkley Valley Museum in Smithers.

Coyle worked with distributors and set up his own factories in Canada and America to make the cartons. But by the 1950s, Hammond says, Coyle faced major competition from others creating simpler egg cartons from plastic rather than moulded pulp.

Coyle simply couldn’t keep up with the change in the industry, his daughter Ellen Myton, who died just before the new millennium at the age of 87, said when she spoke about her father’s legacy with the British Columbia Historical News in 1982.

“Conversion of the plant to new machinery and methods would have involved huge expenditure,” she said.

“As is so often the case with inventors, he was no match for the sharp practices of big business and their sharper lawyers,” his daughter said. “The Coyle carton made several millionaires, but dad was not one of them.”

Her father died at the age of 100 on April 18, 1972. His death certificate identified him as the “inventor of paper boxes.”

“It’s quirky, and yet it’s everyday. Everyone’s familiar with it,” says Hammond. “We still buy eggs lined out in two rows in the same way that Coyle visualized it.”

Dick, at the Perimeter Institute, believes Canadians are creative, thoughtful and willing to take risks, but the Canadian psyche tends to not realize we can be world leaders.

“We’re exactly at that right time in history where we can sort of shift that mindset,” he says.

Among those pushing for change is former BlackBerry co-CEO Jim Balsillie, who said in a recent essay that Canada has the most superficial discourse around innovation policy in any of the 140 countries in which he has done business. He said a successful intellectual-property sector relies on a tightly designed ecosystem of highly technical interlocking policies focused on scaling up companies.

The Canadian government also made innovation a focus of its March 22 budget, using the term more than 200 times. It said it would place “big bets” on sectors including clean technology, agri-food and advanced manufacturing.

One area where Canada is now leading is quantum space, Dick says, saying the country’s researchers in Waterloo, Ont., are believed to be about 15 months ahead of the rest of the world.

He compares the anticipated upcoming second quantum revolution with what happened in Silicon Valley during the digital revolution.

“Being ahead of the curve puts us in the ideal position to attract talent, to attract investors, to just be that hotbed of that innovation into a whole new way to see the world and to change the world.”