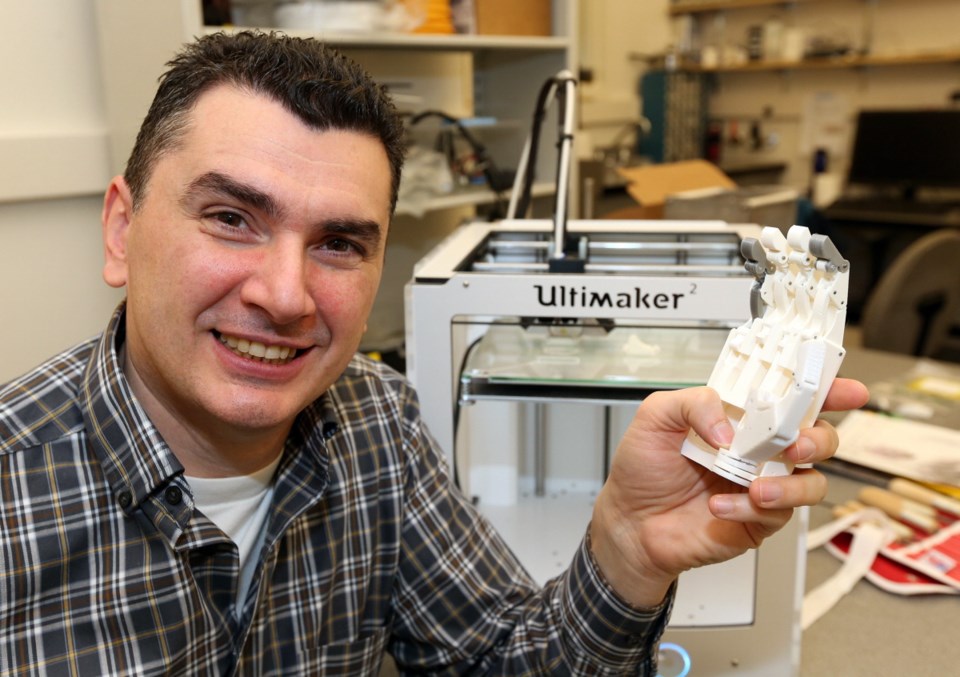

Nikolai Dechev is using the remarkable capacity of 3D printers to produce low-cost prosthetic hands for amputees in Guatemala.

While standard prosthetic hands used in Canada cost about $12,000, and advanced models as much as $70,000, Dechev leads a project that has created hands for only $200 using a 3D printer and spools of hard plastic.

“The price difference is a definite attention-grabber,” said the University of Victoria associate professor in mechanical engineering. “It’s kind of eye-opening, but it’s true.”

One of the cost-saving measures is that moulds do not have to be used.

“When you 3D print, you don’t have any of that overhead infrastructure,” he said. “Really, your only overhead is the printer, and the printers now are super-cheap, they’re like $2,400.”

The $200 prosthetic hand is less durable than the “very rugged” and versatile standard prostheses, but can perform tasks that standard models cannot — such as conform around balls and other objects that the expensive hands can hold only by pinching or grasping in the manner of salad tongs.

A major part of the work has been making the hand design suitable for 3D printing.

The prosthesis doesn’t emerge from the printer as an entire hand, Dechev said.

“It comes out as the pieces, and with about three or four hours of manual labour you assemble it into a hand. What we’re envisioning is basically three standard sizes — small, medium, large.”

The hand is entirely mechanical, using a cable attachment similar to one on a bicycle to allow the device to open and close.

For “light duty” use — such as holding a knife and fork or putting toothpaste on a toothbrush — the $200 hands fit the bill.

Dechev said the printer uses a spool of hard plastic.

The plastic is temporarily melted and squeezed out like toothpaste, then hardens within a minute in the desired form.

The work done at UVic has earned a $112,000 grant from Grand Challenges Canada, a federally funded organization supporting innovative health projects.

“It’s aimed for outreach to the developing world,” Dechev said, adding it is also affiliated with the Range of Motion Project that works with amputees in many countries.

Guatemala has seen a great deal of violence over the past few decades and has a significant need for prostheses, Dechev said.

“In Canada, nine out of 10 amputees are born that way. Down there, it’s something like eight out of 10 are through trauma.”

Most amputees in Guatemala have no options when it comes to prostheses, Dechev said.

“They just go without and they’re highly vulnerable, because if you’re not employed in a country like that, you’re at the bottom. I’m hoping to give them enough function so maybe they’ll have some degree of useful employment.”

Dechev will travel to Guatemala in February for initial trials with people experienced using prosthetic hands and continue work on a crucial part of the final result — the socket that fits over the end of the arm.

The hands must be well fitted to the user.

“The important part is interfacing it to the stump, that man-machine connection,” Dechev said, noting there are plans to produce sockets customized to individuals by the summer.

With a file from Katherine Dedyna