A new study has identified several previously unknown high-risk zones for ship-whale collisions, including a large one off the southwest coast of Vancouver Island.

The research, published in the journal Science this week, marks the first time anyone has quantified worldwide risk of whale-ship collisions for blue, fin, humpback and sperm whales.

“This helps us to pinpoint where whales are most vulnerable,” said Chloe Robinson, an ecologist and director of Ocean Wise’s Whales Initiative who co-authored the study. “There’s never really been anything this comprehensive before.”

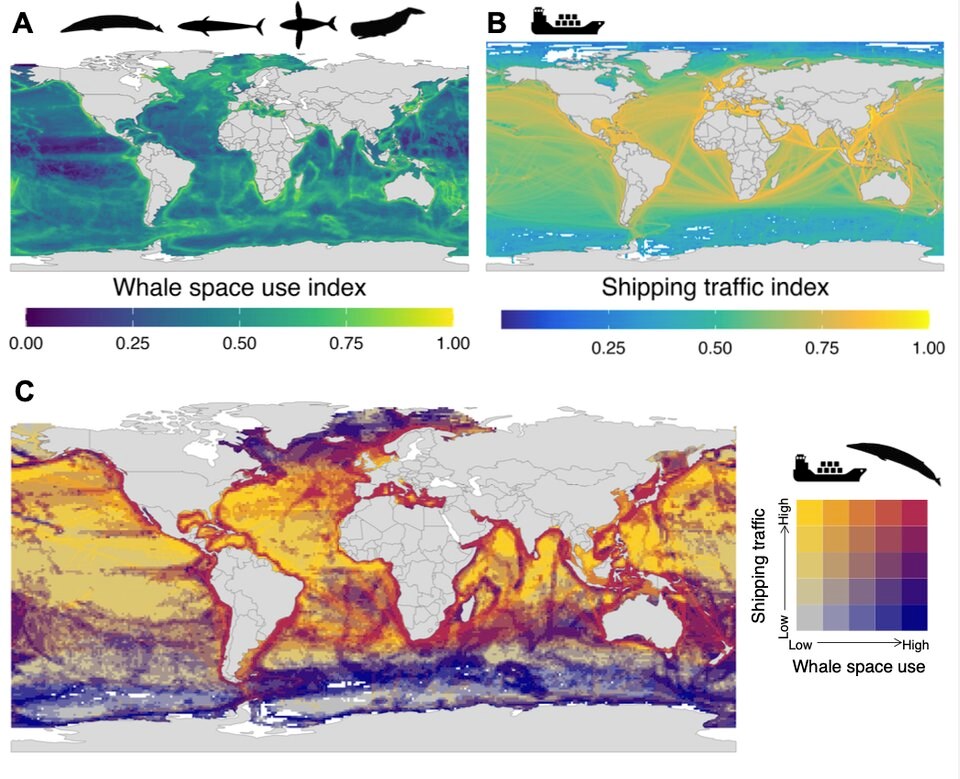

The study found global shipping routes overlap with 92 per cent of the migration routes of four globe-ranging whale species.

Global databases show high risk of deadly 'odds game'

The research team spanned five continents and drew on 435,000 unique whale sightings — from government surveys to sightings by members of the public, animal-borne GPS tags, and even whaling records going back to 1960.

They then compared that data with the movement of 176,000 cargo ships from 2017 to 2022. The vessels were tracked through their automatic identification system and cross-referenced with whale ranges to identify where they would likely meet.

“We’re talking about five billion vessel positions,” said Robinson, who noted a recent study estimated up to 20,000 whales are killed a year through ship strikes. “It’s a bit of the odds game. The more whales and vessels you’re going to have overlapping, the more likely you are that one of those encounters is going to end in a ship strike.”

Along with entanglement in fishing gear, ship strikes represent a leading threat to large migrating whales.

But lead author Anna Nisi, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Washington’s Center for Ecosystem Sentinels, said studying ship-whale collisions can be incredibly difficult, since most of the time, a vessel will strike a whale and it will sink without anybody noticing.

“Sometimes they roll into port with the whale draped over the front of the ship, and that is how they realize that they’ve hit something,” Nisi said.

Ship-strike hot spots pinpointed around the world

In the Americas, the highest-risk areas for whale-ship collisions were found along North America’s Pacific coast, as well as off Panama, Brazil, Chile, Peru and Ecuador.

Robinson said scientists had a pretty good understanding of where vessel and whale routes overlap in Canadian nearshore waters. But move further offshore, and the risks of whale-vessel collisions become a lot murkier — until now.

The study found that off the southwest point of Vancouver Island, a high concentration of vessels are crossing through the same waters humpback and fin whales use to migrate and feed.

The hot spot for ship-whale collisions lies just outside an existing management zone for southern resident killer whales at Swiftsure Bank. The area — which includes seasonal speed limits and fishing closures — extends about 40 kilometres along the west coast of Vancouver Island between Port Renfrew and Bamfield.

A little farther west, the study found what Robinson described as a pit stop on a whale highway, where humpbacks and fins feed and rest before entering the Salish Sea or continuing on their migratory path north and south.

“It is somewhere where if there are strikes, they’re very unreported,” she said.

Ship strikes increasing in B.C. waters

The study comes amid a rebound in humpback whale populations and an increase in maritime traffic. The combination has amplified collision risks, according to Robinson.

Between 2022 and 2024, Ocean Wise tracked at least 15 whale strikes in B.C. waters. And while another recent strike is still being investigated, Robinson says the actual total is much higher, as most collisions go unreported or unnoticed.

“This is something that we see more and more every year,” Robinson said. “Across the coast of B.C., there were at least 10 humpbacks struck in 10 different instances — just last summer. And this is just what we know.”

Humpback whales are born into a life of migration, every year passing between northern and southern feeding and breeding grounds. The whales tend to sleep at the surface during their migration, which puts them at a high risk of being struck.

Vessels have also increased 300 per cent in the last 30-odd years, Robinson. “So it’s a real concern for these species.”

Highest risk of strikes occurs in territorial waters

The study found that more than 95 per cent of the hot spots for whale-ship collisions are near the coast, where countries can protect marine life within their exclusive economic zones.

Yet only seven per cent of the areas at highest risk of collision were found to have any measures to protect whales.

The study found installing management regimes in only another 2.6 per cent of the ocean’s surface would protect whales in all of the highest-risk locations.

“It’s a small percentage, but of course, a very large area,” said Nisi. “This means that there’s just a lot of need and a lot of opportunity to expand these protection measures for whales.”

Long-term co-existence requires collaboration with industry, says ecologist

Efforts to slow and re-route ships passing through whale ranges have improved in recent years. In Sri Lankan waters, the Swiss-Italian-owned Mediterranean Shipping Company has voluntarily re-routed its vessels around an important whale range, said Robinson.

“Striking whales is bad, not only for their image, but for the environment. And they’re supportive of these measures because they’re looking for that long-term coexistence,” she said.

Closer to home, a system of hydrophones, infrared devices and human reporting now informs nearshore whale alert systems from Washington to B.C. and Alaska.

What needs to come next, said Robinson, is to expand that system to previously unknown hot spots farther from the coast, such as the area identified west of Swiftsure Bank.

That could mean extending the Swiftsure Bank management area by as little as a few kilometres to help humpback and fin whales — two species that can’t echo-locate objects like their toothed killer whale cousins.

Infrared cameras can help detect whales

Robinson said one single measure she believes could have a big impact would be equipping vessels with infrared cameras to detect whales within several kilometres. “Maybe some mariners … respond better to knowing there 100 per cent is a whale 200 metres in front of your vessel, versus ‘slow down, there might be a whale here.’ ”

Robinson said such cameras can cost between $50,000 US and $75,000, but they could be an opportunity for businesses to promote themselves as operating in a more whale-friendly manner.

“I know people who have had to go and have therapy after killing a humpback whilst at the helm,” she added.

Without protections, Robinson said, Arctic waters could become the next high-risk hot spot as sea ice melts with climate change, opening up shipping routes.

“Knowing the plans to expand shipping routes into these areas to cut shipping time, make things faster, right through prime whale habitat, I think this is a really good opportunity to get ahead of the issue before it becomes an issue.”

— With files from Brenna Owen, Canadian Press