Canada’s second largest earthquake in 2022 occurred in B.C., a 5.3-magnitude quake off the northwest coast of Vancouver Island.

The largest, a magnitude 5.5, happened in the Yukon, just across the border from B.C. and Alaska.

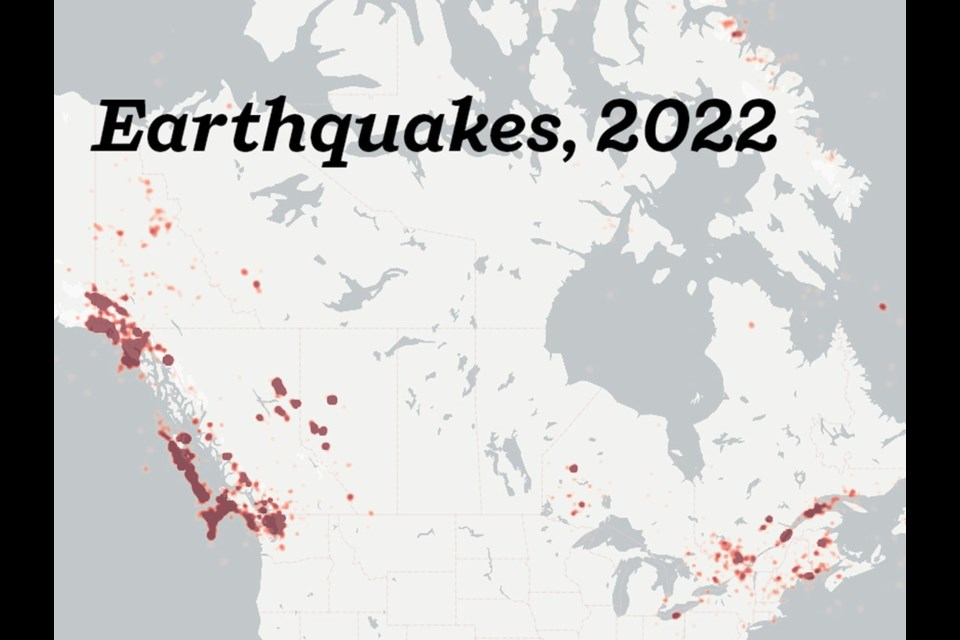

They were two of the roughly 2,500 earthquakes to shake the province last year, most of which occurred in the ocean off the west coast of Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii.

“It’s not unusual to see a magnitude 5.5 or six as the largest earthquake of the year,” said John Cassidy, head of the earthquake seismology section of the Geological Survey of Canada.

“Some years we see much larger than that.”

Cassidy called 2022 “pretty typical” for earthquakes in B.C., which experiences thousands of earthquakes a year. B.C. is the most seismically active area of Canada, according to Shake Out B.C., an emergency preparedness organization.

B.C.’s five largest earthquakes last year were all between magnitude 5.0 and 5.5. Earthquakes below magnitude 5.5 rarely cause damage.

The largest earthquake in modern B.C. history was a magnitude-8.0 quake that took place in Haida Gwaii on Aug. 22, 1949.

Cassidy said that while it is not currently possible to predict earthquakes, the field has changed significantly in the past decade, including improvements in data collection, data quality and computing.

He pointed to a joint project between Canada, the U.S., Germany and Japan that recently mapped the sea floor off the coast “in detail that we’ve never had before.”

“We do have more data, we have more instruments on the ground. So we’re getting better recordings and better information that really allows us to improve our seismic hazard models,” he said.

Two projects that should come online in about a year will offer significant improvements in earthquake warning and safety.

The first, an early warning network that is currently being deployed, is scheduled to be in full operation “in just over a year,” Cassidy said.

“It’s providing seconds or tens of seconds or maybe even a few minutes of warning before strong shaking arises,” he said. “That’s been used in many parts of the world.”

The second is a network of what Cassidy called “strong motion” sensors, which are designed to record very large earthquakes — the kind with shaking strong enough to “toss furniture around and lift people off their feet.”

“We don’t have Canadian data on strong shaking,” Cassidy said, calling it the “most important” data for engineers who design building codes for seismic safety.

“What we’re currently doing in our national building code is we use recordings of strong earthquakes from other parts of the world that are similar to Canada,” he said. “So if you’re in British Columbia, we look at data from Japan or data from New Zealand, where there have recently been some strong earthquakes.”

The current network of seismic sensors in Canada record small earthquakes that would be overwhelmed by a very large earthquake, he said.

“The new instruments that are being deployed will actually be able to record those strong shaking events,” said Cassidy.

Ultimately, being prepared and having solid building codes may be the most reliable protection against earthquakes. Simple steps like having a flashlight or headlamp in easy reach if power goes out and practising the drop, cover and hold on drill can make all the difference in an emergency.

“If you’ve designed your structures and people are prepared and know what to do, then the timing (of earthquakes) is not so important,” Cassidy said.