A Glacier Media project to test B.C. freedom of information laws found municipalities met basic requirements, but varied widely in how they complied with similar requests.

Glacier Media reporters and editors asked 24 municipalities each for five recent records to see if officials could or would comply within the province’s FOI law.

Those records were:

• 2018 and 2019 correspondence between the city and the province on cannabis legalization

• their mayor’s May 2019 calendar

• their city manager’s 2018 travel expenses

• city employee overtime costs

• a list of FOI requests to date in 2019

In 24 of 25 municipalities surveyed in the FOI audit, the municipalities met the 30-day deadline legislated under B.C.’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

In one case, the deadline was missed because the administrator was on holiday.

Officials from six municipalities asked for various clarifications or further information. In six cases, municipalities asked for money to process a request.

In no cases did cities try to negotiate lesser disclosure.

Anyone can request personal or business information held by various levels of government under FOIPPA and the federal Access to Information Act.

What was readily apparent from the audit results was a lack of standardization in record-keeping and disclosure. That hampers people’s ability to access government information.

For instance, the law specifies the first three hours of work on a request are at no charge. The City of Cranbrook lumped all the requests together and estimated it would take 12 hours of work that it estimated would cost $283.50.

One approach all municipalities took: Their mayors’ calendars didn’t mention who they met, merely that there was a meeting.

The cannabis correspondence request, something that requires a relatively simple look at municipal files, proved the most wide-ranging in how it was handled. Nanaimo estimated the cannabis correspondence request alone would take 14 hours and requested $330 for the work. The City of West Vancouver requested $116 for electronic records or $132.50 for paper records on the cannabis request. Squamish asked for $30.50.

All wanted a 50 per cent down payment before work would start. (Glacier chose to abandon the requests rather than pay for records that other municipalities were providing freely, although payment waivers can be requested.)

The findings of inconsistency don’t surprise Mount Royal University journalism professor Sean Holman, a longtime user of B.C.’s FOI system.

He said Glacier’s findings are all too reflective of Canada’s culture of deference, which leads to secrecy, a situation antithetical to fostering democracy.

“We’ve created a real problem in this country because we have such an absence of accountability,” he said.

“Public bodies don’t know how to respond when accountability is brought to bear. It’s actually a lack of understanding how democratic society is supposed to operate. That’s even more troubling.”

Holman said questioning public authorities must become socially acceptable.

“Time and time again, we’ve seen politicians running for office promising transparency and then seeing the seduction of secrecy too strong to resist,” Holman said. “This has been the story of Canadian politics.”

Cannabis

Canada’s federal Cannabis Act came into effect Oct. 17, 2018, establishing a strict framework for controlling sale, possession, production and distribution of marijuana.

All municipalities except Nelson, Prince George and Prince Rupert provided voluminous responses to this request. Nelson and Prince George did not provide government letters, cannabis informational pamphlets or directives disclosed to Glacier Media by multiple other municipalities.

“The city has determined it is not in possession of any records responsive to your request,” a letter from Nelson deputy corporate officer Gabriel Bouvet-Boisclair said. Prince George manager of legislative services Joan Switzer said: “We have received no records responsive to your request.”

This might not be so.

Attorney General David Eby and Solicitor General Mike Farnworth sent an Oct. 4, 2018, letter about applications for retail licences. Most cities disclosed the letter to Glacier. And both ministries confirm Nelson and Prince George were sent that letter.

Switzer later told Glacier the letter is publicly available on the city website in a council agenda.

“Our search for records in response to request … was focused internally searching for records that were not routinely available within the city’s Planning & Development Department, the department responsible for the processes around legalization of cannabis in our organization,” Switzer said.

Bouvet-Boisclair said other cannabis records were on Nelson servers because the city manager was on the Joint Provincial-Local Government Committee on Cannabis Regulation. Nelson chose not to release that data, either.

However, Chilliwack’s city manager was also on the committee and that city disclosed such records.

Chilliwack’s exhaustive response included records from the Liquor and Cannabis Branch and the Agricultural Land Commission, zoning and bylaw information, and communications with multiple provincial government organizations.

Other municipalities’ disclosures fell between the scant Nelson or Prince George responses and the expansive Chilliwack one.

Sechelt requested an extension on the cannabis request, a move allowed if the number of records requested is large or searching would unreasonably interfere with the public body’s operations. The District of North Vancouver delayed release of cannabis information, saying some of it would affect the interests of third parties that would need to be consulted.

The majority released such information without delay.

The mayors

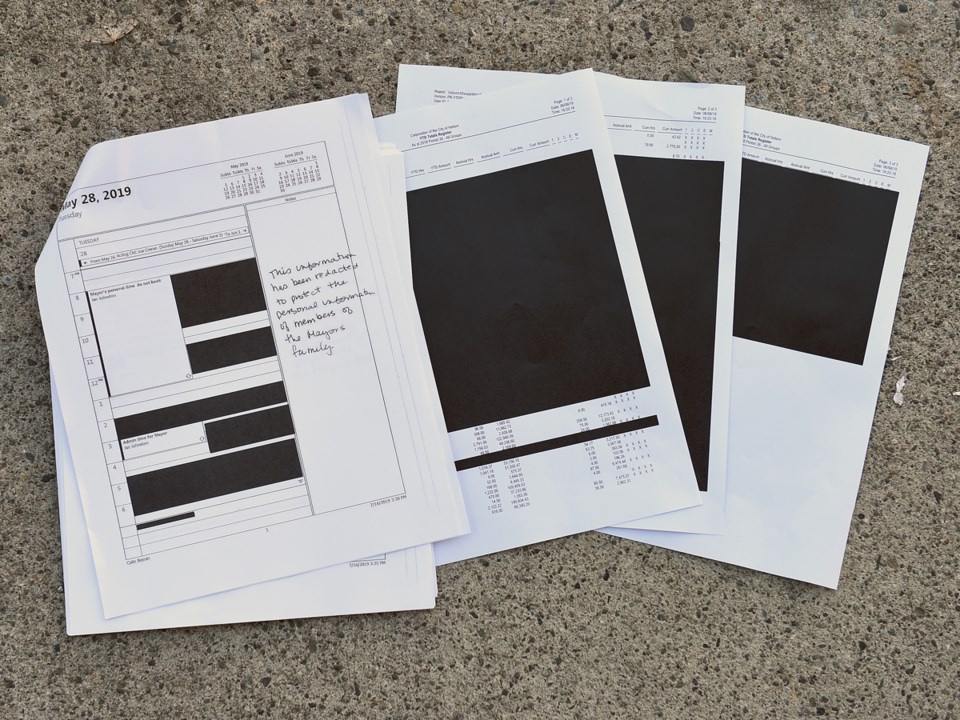

Mayors’ calendars were produced in full by all municipalities, although the names of individuals with whom the mayors met were uniformly redacted.

Kelowna and North Vancouver blacked out entire sections, shielding not just names but also events or groups the mayor attended or met with.

Kelowna noted in page margins that some items were redacted to protect personal information such as names of members of the public or the mayor’s family.

Richmond’s released calendar wasn’t detailed enough to warrant redaction while Prince George’s was very transparent with almost nothing hidden.

Squamish chose not to cite the legislation in redacting a calendar portion, instead marking it “not relevant — private appointment” or “not relevant — meeting cancelled.”The managers

All municipalities except West Vancouver produced city managers’ travel costs. Some went outside the FOI process and pointed to websites with information available publicly without using the FOI process.

Most municipalities provided itemized expenses, including receipts, while the remainder just gave a dollar figure.

West Vancouver’s chief administrative officer reportedly incurred no travel expenses in 2018, the only one to report such a case. The city’s 2018 annual report put CAO Nina Leemhuis’ total expenses at $5,500, up from $4,580 in 2017. Those expenses were not broken down. Vancouver also reported city manager Sadhu Johnston “did not travel on city business during time period specified.”

At the other end of the scale was Prince George city manager Kathleen Soltis who incurred $13,087 in expenses. Prince Rupert’s city manager Robert Long was not far behind at $12,700.

Overtime costs

Municipalities reporting on this issue — generally available without a freedom of information request — came in various forms from just a global number to detailed and itemized lists by name and remuneration.

The highest costs were $4.8 million for Kelowna with a population 132,000 people, while the lowest was for Sechelt at $40,335 with a population of 10,200.

Nelson returned overtime ledgers almost totally blacked out as most information had been redacted except totals.

There was no standardization across the province.

Burnaby did not return a global overtime number, instead providing 43 pages of itemized overtimes from $50.15 in a year for a senior library clerk to $8,720 for a “cross control connection co-ordinator.” Chilliwack sent payroll reports by pay period.

FOI requests

Municipalities’ responses to this query varied, indicating a lack of standardized record keeping or haphazard understanding of what should or could be released.

Some listings indicated names (uniformly redacted) of those requesting information. Others listed the opening and closing dates of the files. Some had details of the request, others just a name. Several were undated.

Chilliwack provided the most fulsome response with not only the details but also copies of the original requests, although personal data was blacked out.

Most cities, except Prince George and Prince Rupert, removed individual addresses of residences, business or accident scenes queried in requests.

Vancouver director of access to information and privacy Barbara Van Fraassen said all FOI requests “that can be made public” are published monthly on the city’s website — 30 days after disclosure to the applicant. She said the city meets all deadlines and tracks average processing times.

Kelowna maintained the most comprehensive file tracking system while remaining as transparent as possible. Only applicants’ names were redacted.

Audits

The role of auditing public bodies for legal compliance falls to the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner. In a 2018 audit of White Rock’s FOI response procedures, the OIPC said public bodies must:

• train employees on the typical steps for searching for responsive records

• train employees on records management, records retention and the appropriate records storage

• adequately document decisions and understand the requirements for retention of particular records

• maintain a record including a reasonably detailed description of the public body’s search for responsive records

• be able to describe potential sources of records, sources searched, sources not searched (and reasons for not doing so) and how much time staff spent searching for records

“Public bodies must respond openly, accurately and completely and without delay,” the OIPC said. “Public bodies must make every reasonable effort to assist applicants by clarifying the request, searching diligently and thoroughly for responsive records and responding in a timely manner. These provisions are central to FIPPA’s key purpose of holding public bodies accountable.”

The OIPC is repeatedly clear on several principles, though.

“The overarching purpose of access to information legislation, then, is to facilitate democracy,” a 2016 OIPC report says, quoting a 1997 Supreme Court of Canada ruling. “It does so in two related ways. It helps to ensure, first, that citizens have the information required to participate meaningfully in the democratic process, and secondly, that politicians and bureaucrats remain accountable to the citizenry.”

The problem, said Holman, is that those principles are frequently ignored as public officials are insufficiently held to account. He said too few are hit with a hard question from a journalist or a records request probing their activities. The result, he said, is that public bodies generally don’t understand how to respond to inquiries.

— With files from Glacier Media reporters and editors throughout B.C.

Municipalities queried were:

• Abbotsford

• Burnaby

• Chilliwack

• Cranbrook

• Delta

• Kelowna

• Nanaimo

• Nelson

• New Westminster

• North Vancouver City

• North Vancouver District

• Port Coquitlam

• Port Moody

• Prince George

• Prince Rupert

• Richmond

• Saanich

• Sechelt

• Squamish

• Vancouver

• West Vancouver

• Whistler

• White Rock

• Williams Lake