Last August, Susan Dulc was working out of her Volkswagen camper van when she got a message: The provincial government needed someone to scoop bat feces from under dozens of bridges.

“The timing worked out well,” Dulc said. “I happened to be travelling back from the Kootenays to Pender Island.”

Over eight days, the Pender resident, a graduate student from Thompson Rivers University, scrambled under dozens of highway bridges adjacent to the Canada-U.S. border. Her target: pseudogymnoascus destructans, or Pd, a fungus estimated to have wiped out at least 5.7 million bats across North America.

Thriving in cool, damp caves, the fungus often creeps over the muzzle of a bat, “like athlete’s foot on your face,” as University of British Columbia bat researcher Aaron Aguirre puts it. Roused from hibernation, the bat’s metabolic rate gets thrown out of whack, leading it to consume precious stores of winter fat.

The fungus can also spread to the membrane of the bat’s wing, where it eats away at the lean skin tissue and hinders its ability to fly. If bats can’t fly, they can’t forage for food. Without enough calories, the mammals risk starvation, freezing and often death.

Peering under B.C.’s border bridges last summer was about finding the fungus, an early-warning sign the disease could come next.

Sometimes, the end abutments were short enough that Dulc and another technician along for the ride could reach the guano by hand. Other times, they used a Dixie cup mounted on the end of a golf-ball retriever — her dad’s idea — to scoop the bat droppings from concrete perches high above their heads.

Once collected, the guano samples were placed in sealed vials and stored in an icebox.

“I think I visited 108 bridges, including some by e-bike in Victoria,” said Dulc.

Eight months later, she received an email only a few hours before the news went public. A sample from Grand Forks had come back positive, the first conclusive evidence the deadly bat fungus had arrived in the province. Dulc remembers feeling dejected.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen,” she said. “I thought we had more time.”

Deadly fungus jumps west

What threatens bats has implications for everything from technological innovation to food production and an individual’s daily comfort.

The echo-location-wielding mammals have inspired blood-clot medications, navigational aids for the blind and sonar. Some bats act as nighttime pollinators. Others disperse seeds or eat insects known to damage boreal forests.

Bats also play an important pest-control role in the city (they eat mosquitoes) and are thought to provide at least $3.7 billion in savings to the agriculture industry every year through their voracious consumption of crop-eating insects.

“The ecosystem service that bats provide is really hard to downplay,” said Aguirre.

Moving down the food chain, bats act as a bellwether for insect health. A missing bat population could be a sign the insects it relies on are also in trouble.

“If you start seeing these declines in these insect populations, it’s gonna be a cascading effect,” Aguirre said. “You have pollinators, you have insects as food sources for other animals. They’re recycling detritus. They’re one of the hardest workers [in] maintaining natural spaces.”

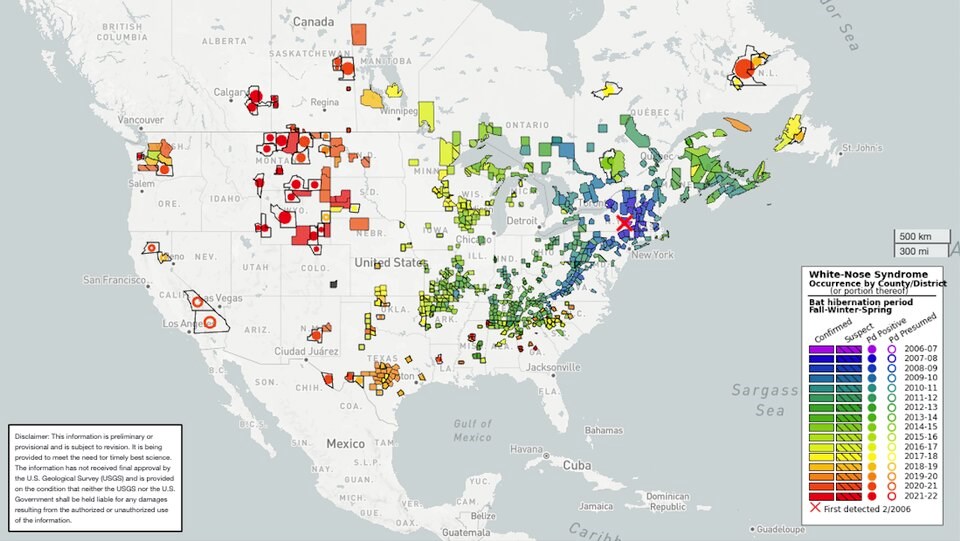

In 2006, that entire web of life faced an emerging existential threat. That year, cave explorers near Albany, New York, first spotted white fuzz growing on bats’ noses.

The following year, biologists in the area observed bats dying in huge numbers. The fungus was eventually tracked back to Europe and Asia, where infected bats don’t appear to be negatively affected. But in North America, the next decade would prove deadly as the disease expanded north and west.

By 2016, white-nose syndrome had spread across five Canadian provinces and half the United States, killing millions of bats with up to a 95 per cent mortality rate.

That year, the disease was confirmed in Washington state’s King County, in what Cory Olson, a bat specialist with Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada, says was a sudden jump. It could have been a recreational caver carrying spores on her equipment, or a bat hitching a ride on a long-haul truck, said Olson.

“We don’t really know. We just know that a bat doesn’t fly from one side of the continent to the other,” he said.

In 2021, Olson found the Pd fungus under a bridge in Saskatchewan, and in January 2023, another sample he collected came back positive in Alberta.

“There’s kind of two waves of spread right now [in B.C.]: one coming from the east and another coming up from the U.S.,” Olson said.

Little brown bats, northern-eared bats and tricoloured bats are all listed as endangered in Canada. Across North America, more than 90 per cent have been killed off.

Another nine bat species are thought to be susceptible to the disease when hibernating, according to the first ever State of the Bats North America report released last month.

In response, B.C. bat scientists have been working under heightened decontamination protocols since 2017. That year, community bat surveillance programs ramped up seasonal testing of dead bats and guano samples in roosts across the Canada-U.S. border.

From September to the end of May, Community Bat Programs of B.C. asks residents to report any dead bats found across the province for testing.

Now that the fungus has been found, scientists like Dulc are scrambling to gather more data. Dulc said she is getting sent back to test the bridges again at the end of May.

Meanwhile, everyone in the bat-monitoring community has redoubled community outreach programs and surveillance near the Rocky Mountains and along the U.S. border.

West Coast bat caves remain poorly understood

There remain a lot of unanswered questions. Michael Anissimoff, a wildlife biologist and chair of Environment Canada’s bat conservation working group, recently learned 500,000 kilograms of bat guano was imported to Canada from places like the U.S. and Southeast Asia between 2008 and 2013.

“Roughly speaking, 90 to 95 per cent of that went to B.C., and 90 the 95 per cent of that went to Grand Forks,” said Anissimoff, who pulled data from the Canadian Border Services Agency.

In 2014, one of his colleagues noticed the practice and triggered a temporary bat-guano importation ban that remains in place.

Andres Dean, whose parents used to run Gaia Green out of Grand Forks, confirmed the company brought in large quantities of guano to feed the cannabis industry.

“A lot of it was being blended and packaged to the U.S.,” he said, adding the company abandoned the use of even domestic guano because they didn’t want to risk transporting the fungus.

Anissimoff says there’s no evidence the import of guano is linked to the positive Pd sample found under a Grand Forks bridge, and even if there was, it would be impossible to trace it now.

What matters, he said, is that illicit bat guano could still be coming into Canada, with even larger volumes moving unrestricted across the country.

“Is there a threat in moving bat guano from Ontario to B.C.? We don’t know the answer to that question,” said Anissimoff. “The government won’t shut that down because we don’t have proper cause … it’s not substantiated enough.

“That’s my next step.”

That risk assessment is going to take significant time and money. Meanwhile, Anissimoff says researchers need to locate bats near the Grand Forks bridge where the positive guano sample was found, attach a transmitter to live bats, and trace them back to where they shelter.

Once they find the cave, they can protect it from human activity and look for white-nose syndrome inside.

Researchers haven’t yet observed West Coast bats facing mass die-offs as seen in the eastern reaches of North America, said Cori Lausen, an adjunct professor at Thompson Rivers University and director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s bat conservation program.

There are some positive signs some of B.C.’s 13 species could be more resistant to the disease. Many of the province’s species tend to hibernate in smaller groups, sometimes under more exposed conditions. Silver haired bats, for example, have been seen hibernating in trees, where freezing temperatures would prevent the growth of the fungus, said Lausen.

At the same time, some of the most common bats in B.C., like the little brown bat, are also some of the most susceptible to the disease and have already faced steep mortality in other parts of North America.

“There’s this whole suite of unknowns,” said Lausen. “We see mortalities in Washington now. But not in these mass die-offs like they did in the east.

“Maybe it’s because the bats are all dying underground. It’s probably because there are so many caves in so many places.”

Finding a bat baseline

According to Aguirre, “it’s just a matter of time” before white-nose syndrome will be found on a bat in B.C.

Bat scientists aren’t waiting. One group at the Wildlife Conservation Society is testing a blend of fungi to inoculate bats.

The idea is to place the fungi on the roofs of caves, where hibernating or roosting bats would rub against the probiotic cocktail. The mix of “good” fungi would then spread across the micro-biome of a bat wing, and crowd out the fungus that triggers white-nose syndrome.

But even if that project proves successful, you need to find the bats before you can treat them.

“They’re devilishly difficult to track,” said Aguirre.

To solve a slice of that problem, the scientist is looking to trace critical bat habitat in places the fungus hasn’t hit yet. Aguirre is planning to ramp up a bat-monitoring project in Metro Vancouver, where urban development and natural areas often collide.

Some studies have shown bats prefer an urban-rural mix, an environment that often provides old buildings for roosting. But light pollution and a lack of natural areas where bats can forage may outweigh those benefits. In other words, it’s not clear how much city is too much city for a bat.

“The sooner we can get an idea of these critical habitat areas, the better chance we have of monitoring and keeping track of these populations. And hopefully, monitoring the spread of white-nose syndrome,” he said.

Aguirre is looking to deploy dozens of ultrasonic acoustic sensors across more than 20 parks in Vancouver, Burnaby and Richmond.

Bats contract their voice boxes or click their tongues to emit echolocation pulses, like high-pitched whale songs. The sound waves bounce off their surroundings, such as a tree, building or insect, and echo back to bats’ ears, offering them a picture of the world around them.

While bats can navigate and find their prey using their highly tuned ears and brain cells, the sounds are out of range of the human ear. Only when Aguirre lowers the frequencies with computer software can the series of clicks be heard — like someone smacking two stones together.

Past studies have shown places like Queen Elizabeth Park in Vancouver, Central Park in Burnaby or Terra Nova in Richmond are bat “hot spots,” Aguirre said.

His plan is to monitor bat activity for a week in each park along transect lines that cross into more urbanized or more natural spaces.

He plans to take the results of the study to city planners and tell them what kind of parks best promote biodiversity. A small park next to a chain of housing developments might not offer the kind of habitat bats would receive in a big park with a water source, Aguirre said.

His work has already produced some short-term results. The Vancouver Park Board recently put on hold plans to renovate several field houses so they could be checked for bat roosts. Those small steps need to be expanded and expanded fast, added Aguirre.

“[Bats are] doing all this great work for us in the insect control,” he said. “This could be an opportunity to coexist.”

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]