The latest online system for B.C. residents seeking income and disability assistance has made it harder to access benefits, says an umbrella group of agencies that help marginalized people.

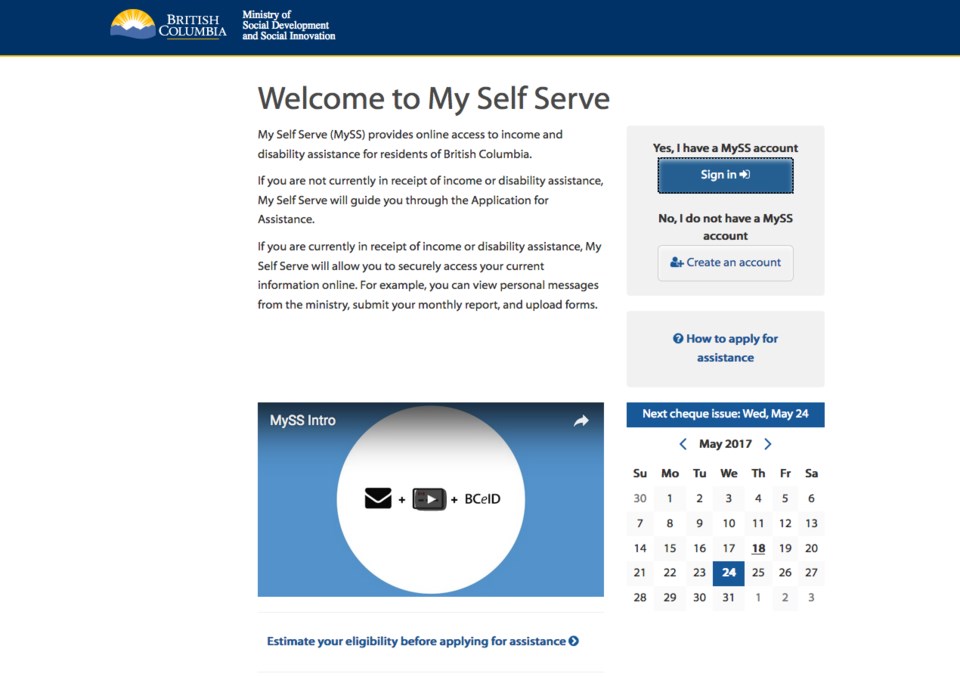

The Ministry of Social Development introduced the “My Self Serve” system this year to replace an application process that at one point required people to view 90 pages online — a problem for people who may not own computers or have strong literacy skills.

Instead, the revamp has sent applicants unable to navigate the system flooding to agencies such as Victoria’s Together Against Poverty Society for help that the non-profits are not set up — or funded — to handle, says the B.C. Public Interest Advocacy Centre.

“It’s downloading what we view as the government’s responsibility onto community agencies that are already completely overburdened,” said Erin Pritchard, the centre’s lawyer.

“We are very much hoping that the new [provincial] government will acknowledge these issues in accessing social assistance and take steps to resolve them.”

It’s hard to estimate the number of webpages applicants now need to go through to apply, because the process is specific to each person. But “it’s more complicated now,” Pritchard said.

Jim Franklin, lead advocate for Victoria’s Action Committee of People with Disabilities, said his agency has helped clients navigate the online application process for financial aid and other services for years, but called the most recent change “insane.”

“I have had the same client three days in a row and I didn’t get through it,” he said Thursday. “I think it’s terrible.”

He has a backlog of problems he’s trying to tackle for people with disabilities, but is bogged down by his attempts to make the application process work.

“I just don’t have the time, especially if it doesn’t work the first time,” Franklin said.

People do go to ministry offices seeking in-person help, but they’re told to complete the application online, Franklin said.

TAPS legal advocate Daniel Jackson has said he met with a client who is homeless and does not have a computer. “The ministry told him he was ineligible for in-person intake because our organization could assist him instead,” Jackson said in a statement, calling the process “cumbersome and time-consuming.”

“If people already stressed by poverty do not have access to a computer or phone, they’re hooped,” Franklin said. “I consider myself to be a very, very helpful person, [so] when it gets to the point where I say: ‘I can’t help you anymore,’ it’s got to be pretty bad. I just resent this very, very much, because it’s not our job.”

Social assistance for one person has been unchanged at $610 a month for a decade. Disability rates were increased in 2010 and again on April 1, to $1,033 a month.

“As the ministry increasingly moves to tech-based service delivery, these inadequate supports have become harder and harder to access,” Pritchard said. “We regularly hear from people who are legally eligible for income assistance, but are effectively denied because of bureaucratic barriers.”

In Victoria, the number of TAPS clients given help related to income assistance has increased more than 20 per cent, to 2,634 people in 2016 from 2,186 people in 2015, said advocate Stephen Portman. Online applications have led to a “substantial” diversion of resources away from complex files, he added.

Pritchard sent a letter outlining her organization’s concerns to candidates in the May 9 provincial election and copied it to B.C. Ombudsperson Jay Chalke. There were 14 responses — one from a Liberal, six from New Democrats and seven from Greens.

“We have requested that the ombudsperson’s office conduct a systemic investigation of the ministry’s polices with respect to barriers in accessing income assistance and have so far been unsuccessful,” Portman said.

A ministry spokesman said he is unable to comment on the situation until a new government is formed.