In a province full of loudmouths, Rafe Mair’s voice always seemed to be among the loudest.

The hotline radio legend was a fierce critic of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords, a fierce opponent of fish farms, and a fierce opponent of “run of the river” hydro dams.

His strong opinions often drew flak, even libel suits. But he didn’t back down.

“If he felt he was right, he didn’t care,” said Shirley Stocker, who spent a decade as executive producer of Mair’s radio show on CKNW.

“When he knew he was on the right path to something, he wasn’t going to take any prisoners.”

On the morning of Oct. 9, 2017, his voice was silenced, when Mair passed away at the age of 85. The news was confirmed on his official website in a brief post. No further details had yet been shared about the cause of death.

Kenneth Rafe Mair was born in Vancouver on Dec. 31, 1931. After graduating from Prince of Wales high school in Kerrisdale, he attended the University of British Columbia, where he earned a law degree. In 1961 he was called to the B.C. bar, and after a few years in Vancouver started a practice in Kamloops.

In 1973 he was elected as alderman in Kamloops, and in 1975, became a Social Credit MLA. He was named the minister of consumer services, then minister of consumer and corporate affairs, minister of the environment, and minister of health. Between 1977 and 1980 he was also responsible for constitutional affairs.

In 1981, he made an abrupt career switch, leaving politics to become a hotline radio host on CJOR.

“I demanded and received a three-year contract at $100,000 per year at a top station, doing their No. 1 show without having any idea of what I was doing,” he noted in his book Rants, Raves & Recollections (Whitecap, 2000).

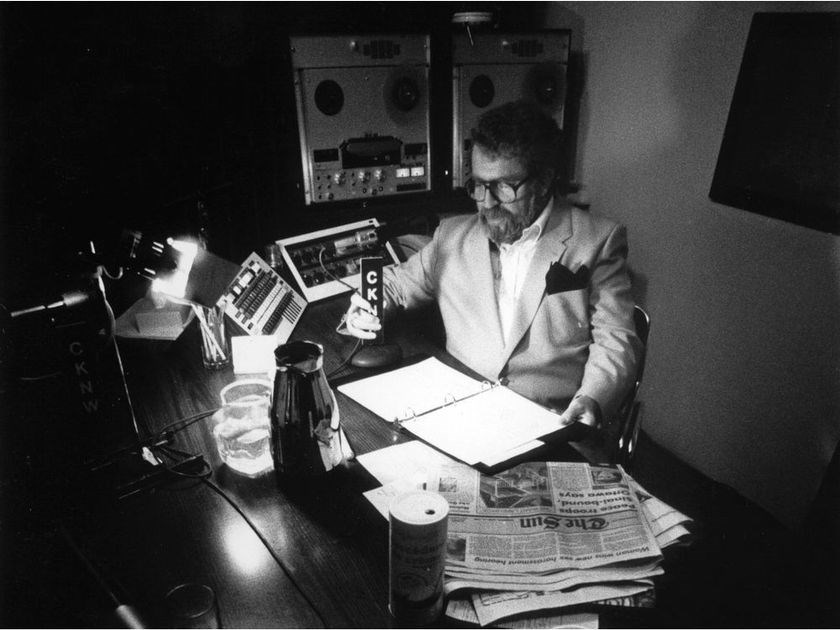

In 1984 he switched to CKNW, where he stayed for almost two decades. At his peak he was the top dog in town, paid $330,000 a year.

“I found Rafe Mair to be one of the most intelligent talk show persons that I have worked with throughout the years, (along with Gary) Bannerman,” said Stocker.

“The two of them were on par in terms of intellect, in terms of understanding what’s going on, in terms of knowing the issues the public are concerned about. From that perspective he was brilliant.”

But Mair wasn’t always easy to get along with.

“He was difficult, but he was honest, and he was fair,” said Stocker.

“He wasn’t as easy to get along with as one would have liked, but part of that is because he was very demanding, and very much of a perfectionist. You had to be on the ball all the time with him, and sometimes you’re not always on the ball, and Rafe would rail at you.”

Many people assumed Mair was politically conservative because he had been a Socred cabinet minister, but he became known as an outspoken environmentalist.

“A lot of my (Social Credit) colleagues used to call me Red Rafe,” he said in 2005.

“I honestly don’t think I’ve changed much over the years. I suppose I’ve gotten more small ‘c’ conservative, which makes me look more left wing. I’m trying to conserve things, which gets in the way of developers and city halls and that sort of stuff. But I don’t think I’ve changed a hell of a lot.”

“He was absolutely for the people, and always has been,” said Stocker.

“He believed implicitly that fish farms were not right. They were not good for the public, they were not good for the environment, and they were not good for the fishing industry itself. He railed on that.”

“He was basically the environmental conscience, or the conservation conscience, of British Columbia,” said David Beers, who published Mair’s columns for several years in the online publication The Tyee.

“He was just a fierce fighter for B.C.’s natural world. The reason he was the conscience of B.C. was that what you saw was what you got with Rafe, he wore his heart right out on his sleeve. He would go anywhere in the province to defend a salmon river.”

His sharp tongue delivered high ratings, and controversy. In 1999, Mair criticized anti-gay activist Kari Simpson, saying her stance reminded him of Adolf Hitler, the Ku Klux Klan and skinheads. Simpson sued for defamation, but lost.

In 2003, Mair had a very public falling out with CKNW and was fired. He moved to AM600, but left there in 2005. In recent years he provided commentary on CBC-TV, CTV and Omni TV, as well as in the Tyee.

He wrote eight books, with titles such as What The Bleep is Going On Here? (Harbour, 2008) and Canada: Is Anyone Listening (Key Porter, 1998). He wrote a column for the Province newspaper from 1995 to 2002, but in 2008 was sued by the paper’s then-owners, Canwest, over a Tyee column. The suit was later dropped.

In 2005, Mair was inducted into the Canadian Association of Broadcasters’ Hall of Frame. Two years earlier, he was also awarded the Bruce Hutchison Lifetime Achievement Awards.

Beers said that Mair was still very popular with the masses, even in his 80s — Mair had three of the top 20 most viewed stories on the Tyee in 2013.

“His public gruffness was not the way he was in person, he was a sweet man,” said Beers. “He was incredibly principled, which is pretty amazing, given that he was a lawyer, politician and a journalist.”

Mair was married three times. He leaves his wife Wendy, as well as children and stepchildren, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.