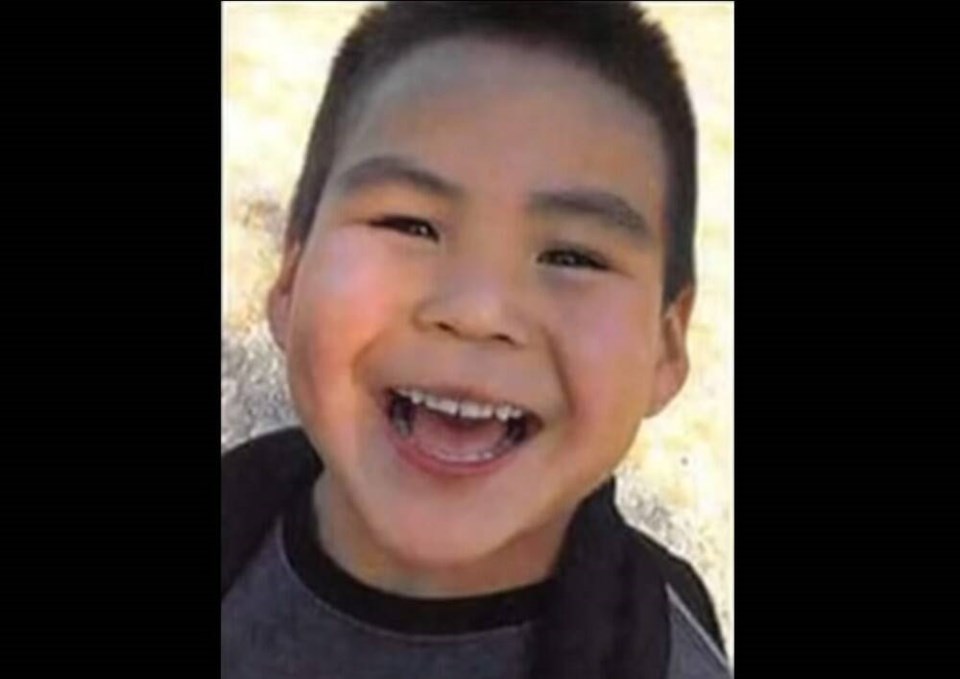

Port Alberni RCMP say they “turned over every stone” and followed every investigational avenue in their four-year effort to probe the March 13, 2018, death of six-year-old Dontay Lucas.

Police had received a report about a child in medical distress.

Dontay’s mother, 28-year-old Rykel Frank, and now-husband Mitchell Frank, 29, were charged on Friday with the child’s first-degree murder. Both remain in custody and are expected to make a court appearance this week.

Const. Richard Johns said the investigation took time time to complete because of the sheer volume of evidence, which included video and cellphone data. Investigators also spoke to dozens of witnesses, Johns said.

Sgt. Clayton Wiebe said the long wait for charges has been frustrating for the boy’s family, his Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation and police officers who worked on the “sad” case.

It took time to gather a large amount of material including reports from the coroners service and other agencies as well as on forensics before the B.C. Prosecution Service could approve charges, he said.

“Television makes homicides look very easy [to solve]. In fact, they’re not. Four years is a long time to wait for answers and unfortunately, these things are just very complex,” Wiebe told a news conference.

He said the couple, who are now married, had other children in their care but they no longer live with them.

A bail hearing for the Franks will be set following their appearance in court on Wednesday, Wiebe said.

“This is a tragic investigation that affected numerous people,” Wiebe said, citing those connected to the little boy, including his classmates.

Wiebe said he could not say why the couple was charged with first-degree murder, which involves intent, because that would be providing details that will have to be revealed in court.

Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, which represents 14 First Nations in three regions of Vancouver Island, said while there is relief that charges have finally been laid, the four-year wait has been hard.

“We’ve been very perturbed that it’s taken so long to do the investigation,” she said. “We’d really love the justice system to do a lot better.”

Sayers acknowledged there is a problem with family violence in her community, saying “we know there is still a lot of work to do to deal with all the past trauma our people have suffered, be it residential school, racism, colonialism.”

She called on governments to provide more funding and support so the Nuu-chah-nulth can do more than they’re already doing to deal with the issue. “We do a lot but it’s never enough.”

Sayers called Dontay’s death a huge loss to the family and many others, noting he was “well-loved” by teachers and students at Haa-ho-payuk School, which he attended. “We all went through some very hard times dealing with the death.”

People note the anniversary of the death each year and there was an ongoing push to get charges laid, Sayers said.

She noted the forensic autopsy took a long time to get done in part because of delays related to COVID-19.

Tribal council vice-president Mariah Charleson said she last saw the boy when he was about three years old.

“I remember him down below in the intertidal zone in Hesquiaht village, and he was just so amazed at all these little crabs. And he would point to a big rock and ask me to flip it over for him. I flipped it over and then you would see his big smile light up.”

Charleson said members of the community are heartbroken by what happened to the boy and know how hard his family has pushed for justice as the years dragged on without anyone being arrested.

“They didn’t stay silent — they continued speaking, fighting for justice for the last four years for Dontay.”

Charleson said the family and the entire community will need culturally appropriate services through a trial that may include disturbing details about how the little boy died.

“That wound is going to be opened up again.”

— With files from The Canadian Press