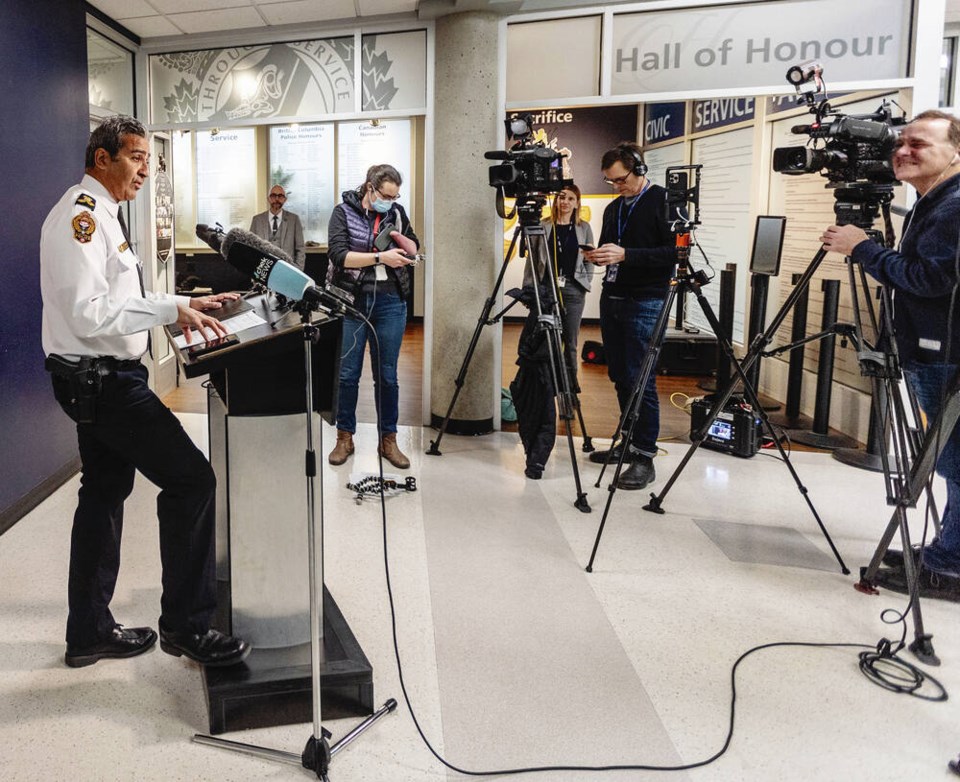

B.C.’s drug decriminalization experiment, which starts this week, will require a “mind shift” by front-line officers, all of whom are required to take online training on the new rules, Victoria police Chief Del Manak told a news conference Monday.

On Tuesday, B.C. will become the first jurisdiction in Canada where people 18 and older found with a total of 2.5 grams or less of opioids such as heroin and fentanyl, as well as crack and powder cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA, also known as ecstasy, will not be subject to criminal charges and their drugs will not be seized.

Instead, officers who interact with someone in possession of drugs will hand out cards with information on local health services.

Manak said VicPD officers almost never recommend charges for simple possession, but when they do, it’s often to bring before the courts someone who is engaged in other criminal activity, and who already has a court order not to have drugs.

“It was a tool in our toolbox that we used sparingly, but that was actually quite effective, so there are some concerns about losing that ability to get criminals before the courts, and not your average drug user,” the police chief said.

“We’re walking down a road that none of us have walked down, so regardless of the amount of training that we’re providing, and the consistency we want, I think there are going to be a few roadblocks and a few bumps along the way — but our goal is to get it right from day one.”

Dr. Scott MacDonald, lead physician at Providence Crosstown clinic in downtown Vancouver, said in Portugal, where drugs have been decriminalized since 2001, “the benefits included reduction in the social harms of drug use, reduction in the transmission of HIV and reduced demand on criminal justice services.”

MacDonald was speaking at a news conference in Vancouver Monday alongside federal and provincial ministers, police and health officials.

B.C.’s Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside said the government has spent $11 million to hire “substance use navigators,” employed by health authorities to connect people who use drugs with addiction or harm-reduction services and other supports, from detox beds to counselling.

Federal Mental Health and Addiction Minister Carolyn Bennett said it’s hoped the exemption will reduce stigma related to substance use, increase access to health and social services and ultimately save lives.

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said she’s been calling for drug decriminalization since April 2019, when she authored a report on the toxic drug crisis, which has killed almost 11,000 people since a public health emergency was declared in 2016.

Stigma around drug use can prevent people from seeking help, leading them to hide their addictions and use alone, Henry said. “In the environment we’re in right now, that means many people are dying alone.”

According to the B.C. Coroners Service, of the 1,827 illicit drug toxicity deaths in the first 10 months of 2022, 83 per cent occurred inside: 55 per cent in private residences and 28 per cent in social and supportive housing, single room occupancy buildings, shelters and hotels.

The City of Toronto has also applied for Health Canada exemption to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, but the federal government has not yet made a decision on that application.

Over the three-year trial, the federal government will monitor data provided by B.C., including uptake of addiction services, drug-related deaths and criminal prosecutions, Bennett said.

Approximately two-thirds of the 9,000 police officers in B.C. have been trained on what decriminalization means in practice, Whiteside said.

Vancouver Police Deputy Chief Fiona Wilson, who is also the vice-president of the B.C. Association of Chiefs of Police, said she doesn’t expect to see any major changes on the ground since B.C. has already had de facto decriminalization for years. In August 2020, Canada’s public prosecution service directed federal lawyers not to seek charges relating to drug possession unless the circumstances are serious.

Critics are worried, however, that the 2.5 gram threshold is too low. Police had recommended a threshold of one gram of illicit drugs while the province applied for 4.5 grams.

“We have no idea starting Jan. 31 if things are really going to change that much,” said Vincent Tao of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users. “We’re going to be making sure at VANDU and across our community that we pay attention to police practice.”

Government officials stressed that police can still lay charges if there’s proof the person with the drugs is trafficking them. Producing, importing or exporting drugs in any amount is still illegal. The exemption does not cover psychedelic drugs, or apply to people who possess drugs in grade schools, licensed child-care facilities or airports, or on coast guard vessels and helicopters. Members of the Canadian Armed Forces remain subject to the Code of Service Discipline.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Consulate General in Vancouver noted crossing the border into the U.S. or arriving at a U.S. port of entry in violation of American laws against possession of illegal drugs may result in denied admission, seizure, fines or apprehension.

Oregon was the first U.S. state to decriminalize some drugs for personal use in 2021. Lawmakers in that state, however, have decried the low uptake of treatment services and the higher number of drug-related deaths.

Kathryn Botchford, whose husband, Jason Botchford, died of an overdose in the spring of 2019, said the well-known Vancouver sports reporter was “a victim of B.C.’s overdose crisis.”

Botchford said she had no idea the father of their three children, aged eight, six and three, was using an illegal substance. “I was so fearful that people would judge him and tear down his legacy. I was fearful that people would judge me for not knowing. And even worse, I feared people would treat my children’s loss of their father as insignificant because of how he died.”

She now openly talks to her kids about substance use and hopes others will have the courage to start their own conversations, Botchford said.

— With files from the Times Colonist and The Canadian Press

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]