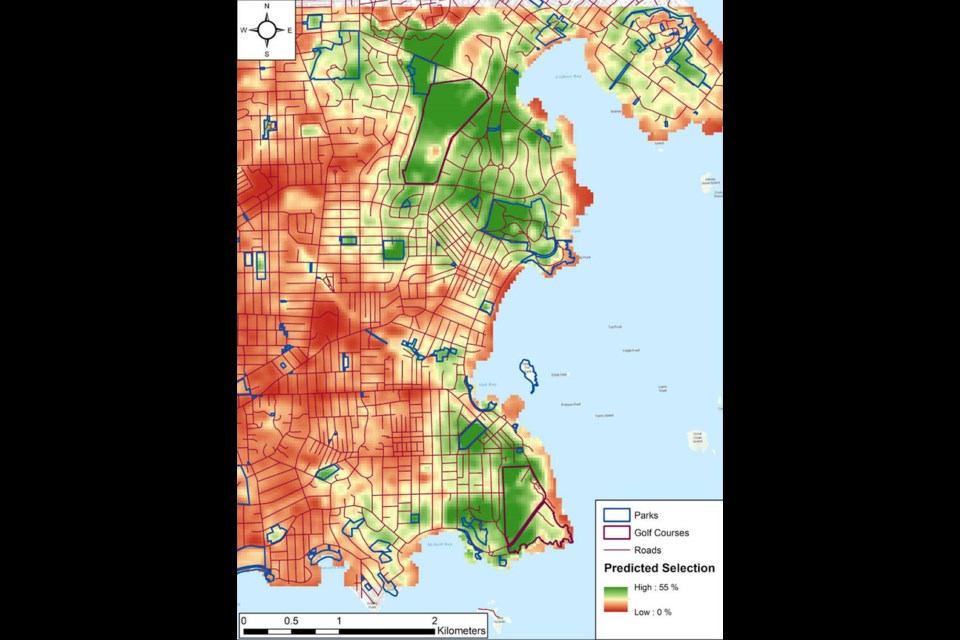

Oak Bay’s black-tailed deer are drawn to large lots with lush green vegetation in the north and south ends of the district, preferring them to small- and medium-sized lots and areas with lots of roads.

That’s one of the findings in a report on deer habitat prepared for Oak Bay council by an independent research team in collaboration with the Urban Wildlife Stewardship Society.

The society, which promotes science-based and humane population management of urban wildlife, collected data over a two-year period from 20 GPS collars placed on female deer. The results were posted on the district’s website this week.

“What’s interesting is it seems like the conversion of the historic, drought-resistant Garry oak ecosystem into the lush, urban landscape may be why we are seeing more black-tailed deer,” said wildlife biologist Alina Fisher, a University of Victoria PhD student in environmental studies.

Deer prefer open meadows where food is abundant and they can see predators coming, said Fisher, and Oak Bay’s large lots with lots of green vegetation are the closest thing.

Historically, the area was a large expanse of the now-endangered Garry oak ecosystem, a habitat associated with extended summer drought, camas and other dry, nutrient-poor vegetation, the report says.

While Garry oak meadows typically become brown and dry in the summer, many properties are “nice and green,” Fisher said. “And that might be providing a lot more vegetation than you would normally find in the summer.”

Deer also like to live near golf courses and parks, where landscaping and irrigation support a greater abundance of plants that grow quickly and stay green, says the report.

B.C.’s urban landscape favours deer, with its absence of natural predators such as bears, wolves and cougars and its abundant backyard gardens and farmers’ fields, the report says. The latter provide ample high-energy and nutritious food for black-tailed deer, which may allow them to breed more successfully and more often than in natural landscapes.

Detailed information on where deer live and forage, what they avoid and their movement patterns is an important tool for keeping their population numbers down, said Fisher.

“If we know where they are, we can focus on these green areas and can try something like immunocontraception or methods to disperse the deer,” she said.

A report on Oak Bay’s immunocontraceptive vaccine pilot project shows a 60 per cent decrease in the number of fawns born in 2020, one year after the start of the program.

ldickson@timescolonist,com