Sooke family doctor Anton Rabien thrives on tracing the first symptom of disease in a patient to a possible diagnosis.

You have to know your patient and be a bit of a Sherlock Holmes to know when persistent abdominal pain is likely an ulcer and when it might be pancreatic cancer.

Even more, he likes the variety involved in being a generalist: managing a patient in heart failure, examining a newborn or performing minor surgery.

So at a time when family doctors are retiring and forced to close practices that new doctors don’t want to take on, what’s luring family-practice doctors like Rabien into the profession?

In the capital region, 18 per cent of the population — nearly 60,000 people — had no regular health-care provider in 2015-2016, according to Statistics Canada. Of those, about half are in the West Shore and Esquimalt.

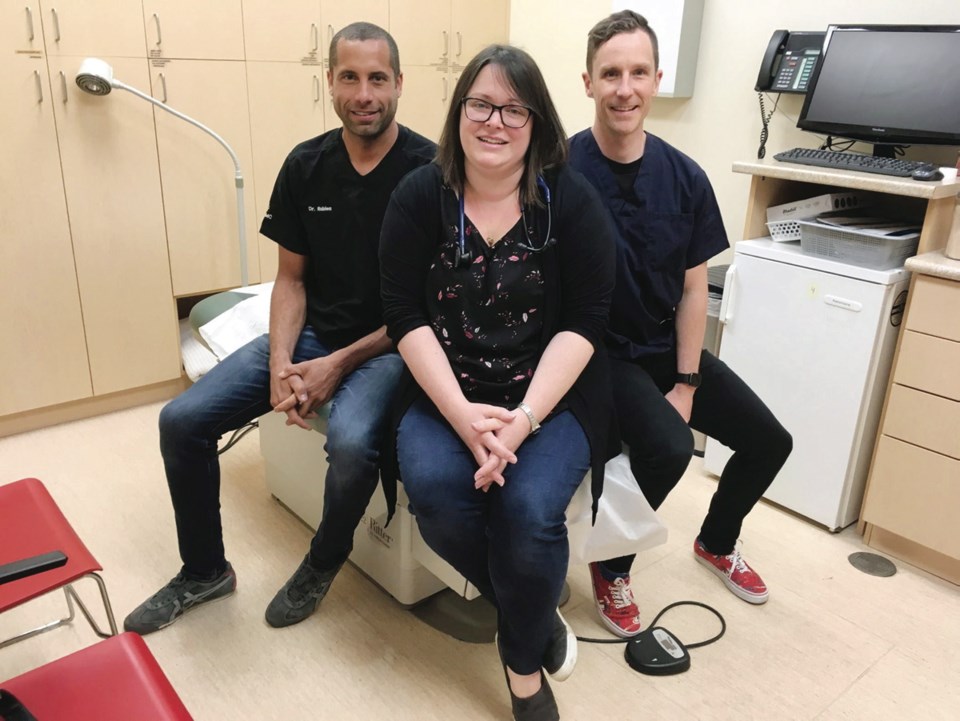

It’s a problem Rabien, 45, and his physician colleagues Hagen Kluge, 37, and Kristi Herrling, 34 — all originally from Sooke — felt a responsibility to address. But not in the traditional way of family physicians buying or establishing their own independent private practices.

Instead, the three sought out a team-based model, where doctors and nurse practitioners are supported by other health-care professionals under one roof.

They’re among nine fresh-faced doctors as well as a registered nurse, a dietitian, a social worker, and several office assistants at West Coast Family Medical Clinic on Sooke Road in Evergreen Centre. Life Labs Medical Laboratory Services is nearby, located in the same centre.

And more doctors are coming: In April, Premier John Horgan announced an expansion of the community clinic’s space and staff “to take up the 4,000 patients that are not attached to a health-care provider today in Sooke.”

The province has pledged $1 million in annual operating funding for two new family doctors, one new nurse practitioner and two new registered nurses. (Two of the clinic’s doctors are leaving at the summer’s end, meaning a total of four doctors now must be recruited.)

The province is also making a one-time $700,000 capital investment to expand the clinic by about 1,400 square feet into the neighbouring H&R Block, with construction expected to start in late fall.

The expansion of the clinic, a hybrid of integrated team-based practice and urgent-care clinic that offers night and weekend hours, is the result of ideas from a working group that includes the mayor, community and health officials and physicians.

The West Coast Family Medical doctors still bill the province for each of the services they provide — a system called fee-for-service — but the health professionals supporting them are paid a salary by the health authority, and eventually, the doctors would like to be on salary, too.

Sooke’s population growth — the second highest in the Island Health region from 2011-2016, after Langford, according to census data — and its location about an hour’s drive from Victoria’s two main hospitals and walk-in clinics made Sooke a priority area for integrated health-care services.

It’s not unusual for a patient to come into West Coast Family Medical Clinic with what physicians there darkly call a “Sooke presentation” of illness.

They come from their homes or the bush or worksites with advanced tumours and wounds that were allowed to fester.

“The breadth of trauma here is much greater,” said Rabien.

After graduating in 2004 with a medical degree from the University of B.C., Rabien knew he’d return home to raise his family and open a family practice, because “the town clearly had a need for physicians, so there’s a sense of duty.”

Rabien bought into a family practice in 2006 that was linked with a satellite office. In 2011, it became the fully integrated West Coast Family Medical Clinic.

Rabien said being early adopters of the province’s integrated primary-care model comes with its own kinks. “There’s no road map,” he said.

There are lots of questions, such as how doctors who invested financially in the current practice can switch to salary, or financially share and manage the expanded clinic with Island Health.

Kluge, who grew up in East Sooke, felt the same duty to return and serve his community, buying into the practice in 2013. He’s raising his family in Victoria, but calls it a “privilege to practice where you’ve grown up.”

Kluge said he saw the success of team-based community health centres while studying at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. The primary health system and health-promotion programs were years ahead of B.C., he said.

Joining a team-based care model here was a “no brainer” for him. “We are able to provide the care that most of us would think is an ideal way to provide care as a family physician,” said Kluge. “Rather than just referring people off, we get to talk to the dietitian and talk to the RN. And we’d love to expand those services.”

Fellow Sooke native Kristi Herrling, 34, followed Rabien and Kluge in 2017.

Herrling had a goal of practising in Sooke since she first applied to medical school. Like Rabien and Kluge, she wanted to raise her children around their grandparents and great-grandparents.

Professionally, Herrling values the health benefits and cost-savings that come with family doctors having a long-term relationship with patients.

“I have families in my practice where I care for three and sometimes even four generations,” said Herrling.

She also believes in the team-based approach. “Often there are multiple challenges facing a patient, some of which may not appear to be traditional ‘medical’ issues, but which absolutely impact their health and may even be preventing treatment of their medical problems,” said Herrling. The ability to refer a patient to other health-care practitioners within the same office “is really invaluable.”

Dr. Vanessa Young, board chairwoman of the South Island Division of Family Practice, has worked more than two decades in family practice in the West Shore and teaches at the University of Victoria’s Island Medical Program.

Young, a family doctor, says West Coast Family Medical Clinic has been able to provide team-based care because of years of Vancouver Island Health Authority funding for allied health-care workers — funding other family practices in the West Shore want but have never received.

Team-based primary care is only one of the solutions the province is funding to address shortfalls in care. The other is urgent-care centres, which cater to patients with problems that should be seen within 12 to 24 hours — for example, a wound or a urinary tract infection — relieving pressure on hospital emergency rooms.

Since it launched on the West Shore in November, the Westshore Urgent Primary Care Centre, open from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., has already seen more than 12,000 patient visits.

Seven others have been announced in the province, including one in Nanaimo.

The debate among doctors, however, is how many resources are going into urgent care at the cost of primary care.

“There has never been an urgent-care crisis in B.C. It is a primary-care crisis,” Young said.

“If primary care was robust, many patients would never end up in E.R. or urgent care centres. They need a GP, not a super-expensive, overstaffed with unionized employees urgent-care centre.”

Last week, family physician Tania Wall told View Royal and Esquimalt councils in a letter that her practice at Admirals Medical Clinic was full within two and a half days of opening.

Wall said she has fielded inquiries from everyone from young families to people in their 90s who have spent more than a decade without a family doctor.

While she is encouraged by efforts to attract physicians to their communities, Wall said she is disheartened by efforts to establish more urgent-care clinics.

“Urgent care and walk-in care are not in crisis in your communities — family practice is in crisis,” wrote Wall. “To increase walk-in and urgent-care facilities is a Band-Aid solution only and should be treated as such.

“We should never let go of the ultimate goal that will improve your population health — the successful recruitment of community-based family physicians to the West Shore.”

Health Minister Adrian Dix, however, argues that people critical of the urgent-care centres aren’t seeing them in the context of the whole primary-care plan, consisting of primary-care networks, urgent primary-care centres and community health centres.

“Some people think urgent primary care is the plan, [but] it’s one element of the plan and it’s connected to the primary-care network, not the other way around.”

Kluge, who has a background in anthropology, said medical interventions in given populations do best when they are tailored to that population.

“It’s tricky to talk about the direction the province is going, because it’s going in so many directions,” said Kluge. “But I think that’s actually a more appropriate way to fund health care. There isn’t one model that works in every community.”

And at least part of the demand for immediate non-emergency health care is coming from patients, said Kluge.

“Certainly there’s a lack of physicians to take on patients,” said Kluge. “There’s also a lack of demand from patients to have a family doctor, even though they say they want one. What people really want is convenience. They want to be seen now.

“For young people who are busy, that makes sense, but for people who have chronic diseases or who are coming back for the same cough over and over again and it turns out to be lung cancer, you are going to miss big stuff that is bad.”

Wall says the high demand for her practice exemplifies the primary-care crisis in the West Shore and beyond, where family physicians are not choosing to open or manage community practices because of soaring overhead costs, dismal compensation, and the high cost of living.

The Colwood Medical and Treatment Centre on Sooke Road recently posted on its website that it would be closed on Sundays until further notice, “due to physician and staff shortages.”

Esquimalt Mayor Barb Desjardins calls the situation in her community a “crisis,” with about 7,000 residents without a physician.

Esquimalt council commissioned a community heath needs assessment that concluded the municipality does not currently have the physical infrastructure to house the kind of team-based medical practice, walk-in clinic, or urgent-care centre it needs.

The municipality is encouraging developers to consider providing integrated medical centre space, with a project coming to a public hearing on Monday for a 3,500-square-foot medical centre. If it or a similar project goes ahead, Esquimalt hopes the province will help fund team-based care in the municipality.

Eric Cadesky, past president of the Doctors of B.C., says only brave new solutions will help the province address the crisis in primary care.

“We’ve largely gotten here because people have been afraid to take risks,” said Cadesky. “The easiest thing to do politically is just to continue on the same path.

“We are trying to treat modern-day challenges with a health-care system that’s been unchanged for the last 50 years.

“There is no way we are going to get this right the first time out. A lot of what we’re going to do is going to be unique to B.C. The only way we’ll know what the outcome is is to go ahead and try it.

“It will require courage, it will require some faith, it will require a lot of trust and what’s important is to recognize we’re all aligned in our common goal of providing the best care possible.”