Canadians need to make sure they don’t become hardened to news about unmarked graves at residential schools after what’s believed to be another discovery of undocumented remains, this time at Penelakut Island, an expert and former judge says.

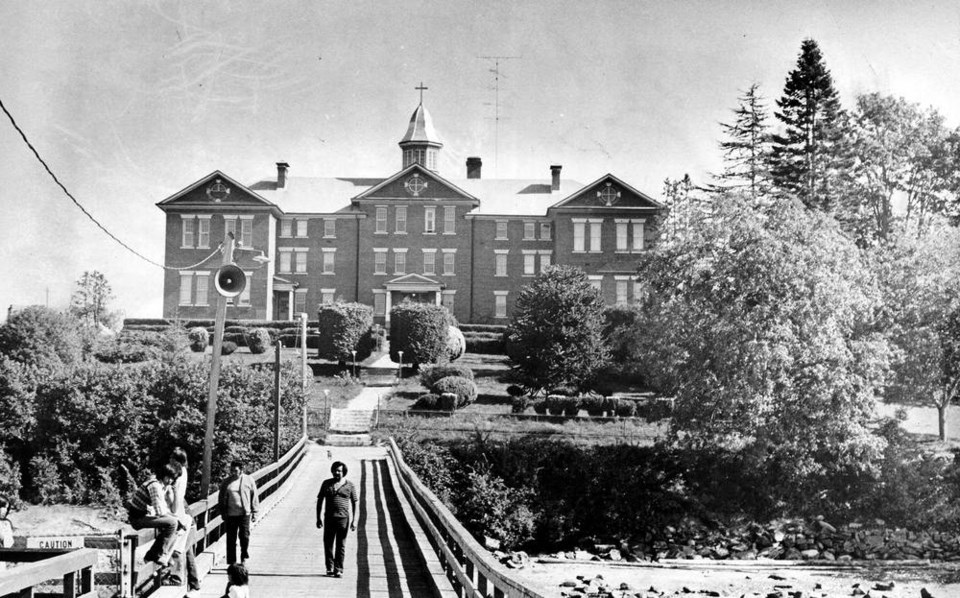

A newsletter circulating online from the Penelakut Tribe says more than 160 unmarked and undocumented graves have been found at the former Kuper Island Industrial School site on Penelakut Island, near Chemainus.

The Penelakut Tribe did not speak publicly about the matter on Tuesday. Chief Joan Brown, elders and other officials said in a statement Monday that healing is an ongoing process and that for some, the burden is too great.

Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, the director of the University of British Columbia’s Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, said she believes Canadians want to see more done.

“I think the response has moved from shock to anger to accountability, but also understanding that this needs to be probed properly,” she said.

“As this information comes out and we see the magnitude of it, we cannot get hardened to it.”

What is also concerning is that the investigation of these deaths has been left to the communities involved, which can be re-traumatizing, she said.

Turpel-Lafond said 107 children, which was nearly half of the school’s student population, died in 1896 when students set fire to the building after administrators cancelled Christmas holidays.

Two sisters are reported to have drowned in 1959 while trying to escape the school.

The federal government took over the administration of the school in 1969 before closing the institution in 1975.

Turpel-Lafond visited the First Nation when she was B.C.’s child and youth advocate, and said the community is still dealing with the hardships caused by the residential school.

“The trauma is enormous. The community has this incredible, historic burden caused by the church and Canada’s residential school system,” she said. “There is the living intergenerational legacy that affects the community.”

Bob Chamberlin, who served as chief of Kwikwasutinuxw Haxwa’mis First Nation for 14 years and is a former vice-president of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, makes it simple to understand what it means to have lost children to residential schools.

Whenever he hears mention of these schools in the news, “I look to the young ones in my life and can’t imagine a moment of happiness following government/church/police arriving one day to take them all away.”

Chamberlin said his mother attended the St. Michael’s residential school at Alert Bay.

“Pick your abuse, put the whole list down and that was my mom’s story.”

When Chamberlin took part in a CBC interview Tuesday morning, he lifted his shy, smiling six-year-old niece up to the camera to say a barely audible “Hi.”

He did this to illustrate how young the students were at these schools.

“We’re talking about children. That’s what I want people to understand.”

Chamberlin, who did not attend residential school, asked: “How many generations of children go through the school in 80 years? This is repeated injustice, over and over and over again on the communities.

“We all have people in each of our individual families that have some measure of trauma or some measure of issue. … Imagine an entire family over seven generations. Then imagine entire communities and nations over seven generations.

“When I think of it like that, I think about how wonderful strong our people are.”

Residential school tragedies are a slice of what Chamberlin sees as systemic racism at the federal level.

He recommends federal parties get together before the next election is called to establish a new department. It would have the job of tackling recommendations coming out of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Truth and Reconciliation Report, and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

“I bet it could happen,” he said. But he’s not hopeful, saying the federal approach is to deny, delay and distract.

The National Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419 to help survivors of residential schools.

- - -

To comment on this article, email a letter to the editor: [email protected]