As a child, Emma Fillipoff kept some of her favourite things inside a pretty locked box. A flower petal or a rock might not mean much to others, but they had special value for the shy and sensitive girl growing up outside Ottawa.

Emma stood out from her three siblings, all outspoken and extremely competitive athletes. Emma never played sports; she loved dance class. She performed until she was 15, but gave it up when her coaches wanted her to compete.

Competition wasn’t her thing, said her mom, Shelley Fillipoff, who spent every day for more than two months in Victoria searching for her missing daughter.

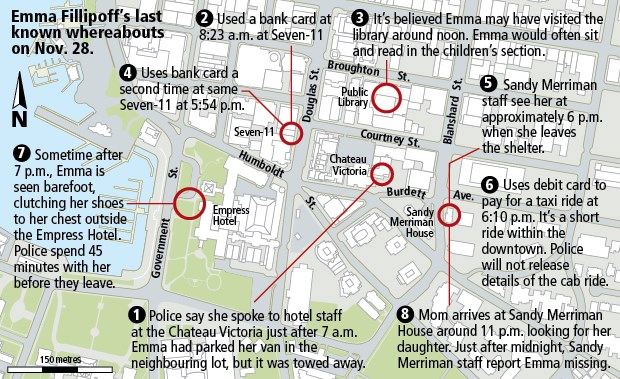

Emma reportedly left a women’s shelter about 6 p.m. on Nov. 28. She was last seen more than an hour later, walking barefoot in front of the Fairmont Empress Hotel on Government Street.

A passerby saw her and called 911.

While Emma was talking to police in front of the Empress, Shelley was flying to Victoria to help her daughter move back to Ottawa.

Instead, when Shelley arrived just hours later, she began the long and gruelling hunt for her daughter. Unfortunately, Emma’s private nature left a sparse trail, making the search extremely difficult.

After two months of looking, on the morning of Feb. 5, Shelley flew home without her daughter.

“It’s time for me to go,” she said from her hotel room the night before she left.

“I don’t want to because it feels like I’m leaving her behind, but my other kids need me, too. It’s time.”

- - -

Shelley used a downtown hotel as her base during the search, which included every municipality in the region, other cities around Vancouver Island and many Gulf Islands.

Theories about Emma’s whereabouts changed almost daily in the beginning. At first, Shelley expected to find her daughter hanging out somewhere in the city.

Within the first 24 hours, Shelley walked through Beacon Hill Park and along the beaches near Dallas Road, because she had heard that was where her daughter liked to spend time.

“I thought I’d just come across her,” Shelley said.

“I thought she’d just be sitting there taking pictures or something.”

Emma was a trained photographer and chef, who became even more of a recluse as an adult.

Those who knew her in Victoria said she kept to herself and would share little about her life. She told people how much she loved her family, but rarely talked about them.

When she talked to her family, she revealed little about where she lived or worked.

Shelley knows that Emma had an apartment when she arrived in the fall of 2011. She held several jobs in the past year, including one at Red Fish Blue Fish, the seasonal seafood restaurant in Victoria’s Inner Harbour.

“Emma has always been that way,” Shelley said. “She was always very private. But I think that might have gotten worse in recent years.”

Just days before she flew to Victoria, Shelley learned that her daughter was staying at Sandy Merriman House women’s shelter. Emma stayed there several times within an eight-month stretch. In total, she stayed about four months, usually a month at a time.

Emma was not in a good state of mind, her mother concluded after talking with people who saw her in the days before her disappearance.

“People said that in the last couple days, she was seen standing in the street so confused she couldn’t even get across the street,” Shelley said. “Everybody has ruled out drugs. Staff at Sandy Merriman, they deal with addicts all the time, and they said this was [most likely] a mental breakdown.”

There’s also an indication Emma could have been suffering from an eating disorder, which would not help her state of mind.

“It would appear she was trying to find her balance in the world, including finding ways to eat just enough to sustain herself,” Shelley said.

Emma’s behaviour in the days before she disappeared indicate she was planning to return to Ottawa.

The police investigation revealed she had a tow-truck driver pick her up at the shelter on Nov. 21. They drove to Sooke, where Emma stored her van, then brought it to a parkade in downtown Victoria.

Shelley has since spoken to the driver, who said Emma was planning to surprise her family by going home. The driver said Emma looked up at the snow on the mountains and said she couldn’t wait to get home where she could see the sun and the snow, Shelley recalled.

Two days later, she called her mom, crying on the phone. She wanted to come home, but the move wouldn’t be easy. All her things were locked up in her van and she wanted to make sure it was all safe.

Shelley offered to help and agreed to fly out. She bought a plane ticket, but then Emma asked her not to come. Mom cancelled her flight.

“She wanted to do it on her own,” Shelley recalled.

The plans changed several times until, finally, Shelley flew out without Emma knowing. She arrived just hours too late.

Emma left the shelter about 6 p.m., according to police reports. Just more than an hour later, police received a call about a woman walking barefoot in front of the Empress.

Investigators tell Shelley that the attending officers talked to Emma for about 45 minutes before leaving her.

“I could see Emma telling them that she was totally fine,” said Shelley, adding her daughter was apparently carrying her shoes and appeared disoriented.

As more information came in, the search for Emma broadened. Within days, Shelley and a team of volunteers had postered most of the region. Days after that, they were reaching as far away as Port Renfrew, Tofino and Campbell River. Shelley herself visited many of the Gulf Islands.

But after two months, Shelley had to head home.

The worst part about leaving is the unanswered questions: Why would Emma leave behind everything she owned? Why, after days of reaching out to her mother, would the phone calls stop? Did she have a mental breakdown? Does Emma want to stay hidden? And, of course, the worst questions: Did someone hurt her? Did she hurt herself?

If Emma wasn’t so private, there may be more clues, but Shelley remains confident the answers will come. For now, however, she’ll keep her daughter’s things in storage, under lock and key.