The federal government has announced tough new restrictions on fishing for chinook salmon that recreational fishers say will have devastating consequences for their industry.

Federal Fisheries Minister Jonathan Wilkinson said the measures are necessary to protect Fraser River stocks for future generations.

“A lack of action today could mean the extinguishment of some of these runs and ultimately of the Fraser chinook entirely over time,” he said in an interview.

The federal government said chinook, which are prized for their size, have been in decline for years due to fishing, habitat destruction and climate change. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada assessed 13 Fraser River chinook populations and determined that 12 of them were at risk.

Wilkinson said the measures announced Tuesday establish a recreational catch-and-release fishery until mid-July in most areas to allow the maximum number of chinook to return to their spawning grounds. After that, fishers will be able to keep one to two chinook per day depending on the area and time of year.

“And that is really a function of the fact that the endangered stocks will have moved through these areas by that time,” he said.

In addition, the federal government is closing the commercial troll fishery for chinook until Aug. 20 in northern B.C., and until Aug. 1 on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

“We’re also restricting food and ceremonial access for First Nations until July 15,” Wilkinson said.

He acknowledged that the measures will have an impact on people.

“I certainly understand the perspective of the recreational fishing community,” he said. “I used to be a fishing guide and my father used to own a fishing camp. So I do understand that.

“And what I think we’re striving to do today is to ensure that we’re actually protecting these stocks for the future.”

Owen Bird, executive director of the Sport Fishing Institute of B.C., said he was “disappointed and frankly a bit shocked” by the decision.

He said the institute recognizes the importance of conserving chinook for future generations. He said the government had proposed a scenario that would have done that, while still allowing fishing opportunities for small businesses and coastal communities. Instead, he said, the government took a far more stringent approach that will hurt a sport fishery industry that brings in $1.1 billion in revenue annually and employs 9,000 people.

“This could affect hundreds of millions of revenue,” he said. “This could affect a good amount of those 9,000 jobs.”

Karl Ablack, vice-president of the Port Renfrew Chamber of Commerce, said the measures will be “more than difficult” for sports fishing businesses that are being asked to condense an already short season.

“This is going to be a significant impact on those operators and I’m not sure all will survive,” he said. “I think it’s going to cause a lot of pain within some of the coastal communities based on what we’re seeing.”

Jeffery Young, a senior science and policy analyst with the David Suzuki Foundation, said the government had little choice. “We know these chinook are endangered and threatened,” he said. “We know that returns last year were particularly low and that we expect them to be potentially even lower this year.

“So we’re really at a point where there really isn’t harvest available on these chinook, and that any fish that we can keep in the water and either get into the mouth of an endangered killer whale or up to spawn and rebuild the population is a valuable fish.”

Brian Riddell of the Pacific Salmon Foundation said the federal government has tried to take into account the social, cultural and economic impacts of its decision. “But if what they’re saying about the chinook trends is correct — and I think I have to agree from everything I’ve seen — I don’t see that they had many options. They were backed into a hard place.

“I think one of the really strong points is that the declines we’re seeing in chinook in southern B.C. are going on pretty much coast-wide right now from Alaska down into California. So we know that there are significant reductions in their production and the rate of production, so there’s really not an allowable harvest in the strict sense for chinook in our area, right now.”

The measures announced by the government include:

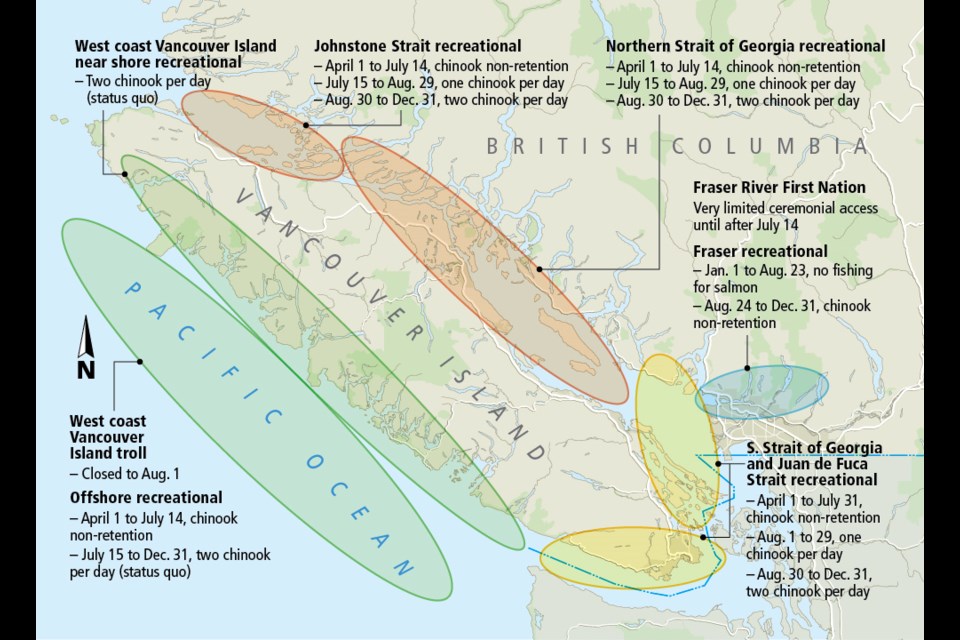

• Catch and release of chinook in southern B.C. — including Johnstone Strait and northern Strait of Georgia — until July 14 followed by a daily limit of one chinook per person per day until Aug. 29, and then two per day until Dec. 31.

• Catch and release of chinook in Juan de Fuca Strait and southern Strait of Georgia until July 31; then a limit of one per person per day until Aug. 29 followed by two per day until Dec. 31.

• Catch and release of chinook on the west coast Vancouver Island offshore areas until July 14 followed by a limit of two per day until Dec. 31.

• A limit of two chinook per day on west coast Vancouver Island inshore waters once at-risk chinook stocks have passed through.

• Closure of Fraser River recreational salmon fisheries until at least Aug. 23.

• Reduction in the total annual limit from 30 to 10 chinook per person.

Besides the new fishing restrictions, Wilkinson announced a series of talks with First Nations, the B.C. government and other groups over the next few weeks to discuss broader issues affecting salmon stocks.

— With a file from Carla Wilson