The number of fluent First Nations language speakers in B.C. are dwindling, but a new report shows the number of people learning the languages is on the rise.

“The decline of fluent speakers is not a surprise because many elders are getting on in age,” said Lorna Williams, chairwoman of the First Peoples’ Cultural Council, which undertook the study. The Crown corporation was created in 1990 to advocate for arts, language and culture.

“But there is cause for celebration when you look at all the new learners. Everybody says it is an impossible task because of the diversity of the languages, because they’re not spoken, but it’s happening.”

Williams was joined by elders, fellow educators and community members Friday at the Lau,Welnew Tribal School in Tsartlip to launch the Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2014. The event began with a welcome song in the Sencoten language by a group of children. The school has First Nations language immersion programs from preschool to Grade 1 and a successful adult language mentorship program. Sencoten is the language of the Wsanec (Saanich) people.

“We know programs like this work, when the community is mobilizing, archiving and documenting,” Williams said. “But there is still a lot of work to do. Communities everywhere are at different levels.”

This year’s report found there are 5,289 fluent speakers of First Nation languages in the province — down 320 from the 5,609 recorded in the 2010 report, the organization’s first on the subject. Only 52 per cent of First Nations communities said they have curriculum material to teach languages.

However, semi-fluent speakers have increased by more than 3,000 in the past four years.

Semi-fluent speakers and language learners make up nearly 10 per cent of the province’s First Nations population. British Columbia is home to 34 First Nations languages, which is 60 per cent of those in Canada.

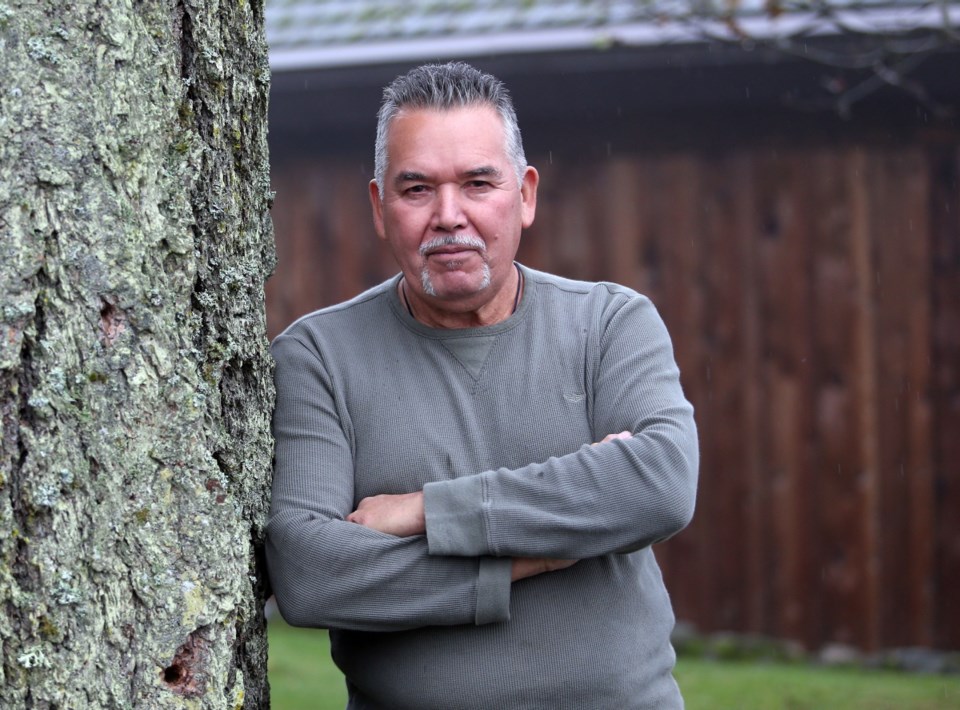

“We’ve seen an explosion of interest in the languages in the last five years,” said John Elliot, a First Nations language champion and educator for nearly 30 years.

Elliot grew up in the Tsartlip community, with his parents and relatives speaking Sencoten with each other, but not with the younger generation.

“There was still some trauma with being told not to speak [their language] at [residential] schools, so they were not willing to pass it on at that time. This created a big gap, which we’re still trying to overcome,” Elliot said.

When he was in his 20s, he pursued his interest in the language through local elders. “At that time, there were 18 fluent speakers. … [Now], they are all gone.”

His sister also became a language-revival champion, while his father went on to create an alphabet for the language and his mother, now 94, is one of the last living fluent speakers of Sencoten — and a mentor to others.

“It puts a lot of pride into [students] when they can speak their language, a presence and connection to the land,” he said, noting First Nations languages are not just about words. They also convey a world view and culture.

“Take hunting. We view it as for survival, not a sport. Deer has a name and a prayer name. It’s called ‘grandson.’ This makes us think of the future. It’s not killing for killing — it’s to survive and sustain.”

Elliot credits immersion programs and a master apprenticeship program, in which adults pursue a bachelor of education working one-on-one with an elder, for helping renew interest in First Nations languages in the Tsartlip community.

“We’ve come a long way, but there is a long way to go,” he said.