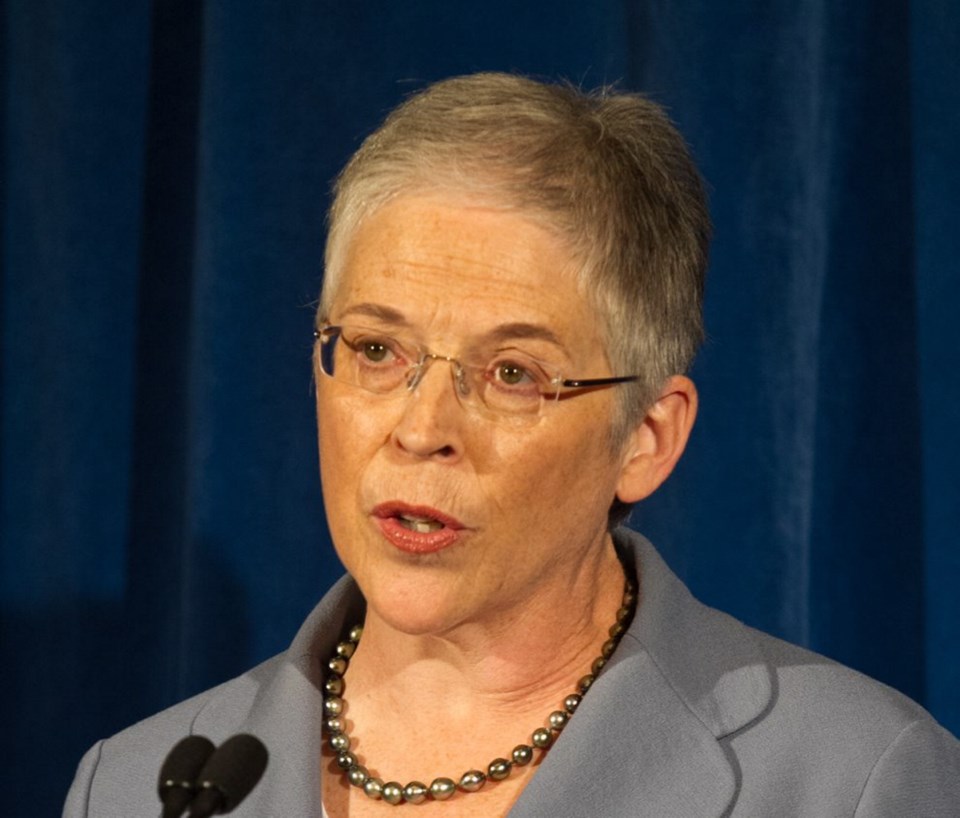

VANCOUVER — Margaret MacDiarmid, the former Liberal health minister whose political legacy is linked to the health scandal that engulfed B.C.’s Liberal government, has opened up about one of the darker periods of her life.

MacDiarmid said it took years for her to discover that information she received in her first 2012 briefing by her deputy minister, Graham Whitmarsh, contained largely incorrect information about health-data privacy breaches, based on whistleblower allegations that were not — and would never be — substantiated.

Whitmarsh used his authority to suspend and fire eight researchers, just as MacDiarmid was taking the political helm of the ministry. MacDiarmid, 60, said she doesn’t know if there was anything intentional about the misinformation she was given.

“I have no reason to think it was deliberate. But I don’t know.”

In her first comprehensive interview about the scandal, MacDiarmid said that in the initial briefing with Whitmarsh after she was named health minister, he told her that the ministry had already spent many months investigating allegations of misconduct by ministry researchers and the internal probe had “revealed some very serious problems.

“Some people had already been let go or were about to be. I was told that peoples’ personal health information has been used for purposes it wasn’t supposed to be used for, and it might have been put on [unencrypted] thumb drives and the ministry didn’t know where they were. I felt the public had a right to know, to be informed of that, so I gave a media briefing the next day.”

She said she would only learn the facts, years later, from various sources including the lawyer who defended her on defamation charges and the 2017 B.C. Ombudsperson report into the scandal.

“So what I know now is that a lot of what I was told is inaccurate or actually not true. But at the time, how could I have done this differently or avoided the long and painful lawsuits?” she said.

Lawsuits filed against the government and MacDiarmid were ultimately dismissed by consent after then-health minister Terry Lake, who succeeded MacDiarmid, acknowledged and apologized in 2015 for the “heavy-handed” way government handled personnel issues while investigating allegations.

Asked why Whitmarsh would give her information containing so much unproven, inaccurate information, MacDiarmid said she remains baffled.

“I have no idea, I’ve never spoken to him about it. I’ve never seen him or had anything to do with him since being unelected [in 2013]. In previous ministries, I had so much confidence in deputies, so if one of them said someone was being fired, I would not have even thought about what is the process, the rules for the civil service. It’s the responsibility of the deputy, not the cabinet minister, so it never occurred to me to ask those sorts of questions,” she said.

“I’ve never had a situation where I was told things that weren’t true, things that I then went out to the media and said, that ended up being not true. It was not part of my experience with other deputies and I had had three before that.”

Reached in the Bahamas, where he works as a health consultant and lives part time when not in Vancouver, Whitmarsh said he was “disappointed” to hear about MacDiarmid’s comments. But he said he relates to the emotional toll on MacDiarmid because he, too, has regrets about the scandal.

“I never knowingly misled any cabinet minister that I dealt with. Indeed, I believe that I had a reputation for being direct and straightforward,” Whitmarsh said. “Clearly, if we had known then what we know today, I expect all those involved would have handled matters differently.”

MacDiarmid said she was told during her first briefing that ministry officials had asked the RCMP to investigate. At a news conference on Sept. 6, the day after she was sworn in, MacDiarmid announced that some employees had been dismissed and the RCMP had been asked to investigate. But that gave a false impression that a criminal case was underway when, in fact, the police had not committed to conducting an investigation. A corresponding media statement also mentioned the RCMP.

The police never found grounds to launch an investigation — and did not launch one, something the public learned only much later.

One of the researchers fired in 2012, Roderick MacIsaac, committed suicide in 2013.

Some employees eventually got cash settlements and their jobs back, and apologies were made by then-premier Christy Clark.

The situation was documented in a ombudsperson’s report, which found government lacked evidence to fire workers, botched internal probes and smeared reputations of the health researchers, in no small part because of MacDiarmid’s reference to the RCMP in her initial news conference.

In his report, ombudsperson Jay Chalke said the firings were driven by a flawed, rushed investigation and that the government misled the public about police involvement.

Asked if she was told to say the RCMP were involved at her first news conference as health minister, MacDiarmid said: “I wouldn’t put it that way.

“When a minister is going to have a conversation with the media, information is provided. The explanation I recall is that health information, thumb drives and that sort of thing, were considered to be property, and it wasn’t known where they were and so that could be considered to be a crime and that the ministry had approached the RCMP. It was part of the briefing notes.”

In hindsight, MacDiarmid concedes she could have taken more time to drill down for more information from a variety of sources besides her deputy minister.

Asked if she agrees history will show she was too trusting, she said: “I had been a cabinet minister [for three years] and I had never had a briefing from a deputy that was inaccurate. There might have been some facts that needed fact checking, but not something this glaring.

“But I take your point. Was I naive? That’s very fair. Trusting? Yes, but there’s a reason I was trusting. I did not become aware of many things that had gone wrong with the investigation until two years later. Lawsuits were all dropped against me, but it was very late in the day that I become aware of things that went wrong at various levels of the ministry.”

The ombudsperson’s report, which found the government was wrong to fire the researchers, says there were scrambled, 11th-hour internal debates and legal opinions cautioning against the police mention, but government communications officials pushed for mentioning it. Chalke found the Ministry of Health needed to beef up health data handling and security practices and he faulted the ministry for not “translating privacy and security policies into meaningful business practices.”

MacDiarmid said for her, the years since the scandal have been marked by long stretches of anger, resentment, regret, “but mostly sadness.”

MacDiarmid said the intervening years have not helped her reconcile the scandal and her role in it.

“I loved that job as MLA, but reconciling it, I did go through a period of time of being terribly sad, feeling lost, dealing with all the legal examinations, being accused of horrible things like defamation of character,” she said.

“In some cases, I was given information in documents that had never been provided to me before when I was the minister. I am not going to get an explanation for why I was kept in the dark. . . . My lawyer couldn’t even tell me a lot of information because he said when I testified I had to say what I knew. He couldn’t contaminate my memory by telling me other stuff that was found out later. I had to testify about facts as I knew them.”

Some political observers were surprised when MacDiarmid ran for re-election in 2013. The Liberals won a majority, but she lost to the NDP’s George Heyman, who still holds the Vancouver seat. MacDiarmid said the scandal wasn’t the issue that sunk her on election day.

“You know, only a few people mentioned it to me when I was door knocking. The big issues in Vancouver-Fairview during the campaign were pipelines, oil tankers and film industry [tax credits]. Those are the issues that took me down.”

She acknowledged that serious health problems — breast cancer and meningitis — in the years preceding the scandal, and then the scandal itself required an abundance of resilience.

The former president of Doctors of B.C. said political life actually proved to be helpful. “I had not thought of myself as a particularly strong person, but I handled certain things, came to see myself as a strong person,” MacDiarmid said.

“I really do feel well now. The changes I’ve made in my lifestyle have made a huge difference. There was one time during the legal process when I was particularly demoralized and I went to church and heard a sermon about how things aren’t always fair and never will be.

“You can’t always reverse people’s bad opinions of you. The facts you want to get can’t always be obtained. When I started writing things down, I realized how difficult it was for me and so profoundly terrible for so many other people within the ministry.”