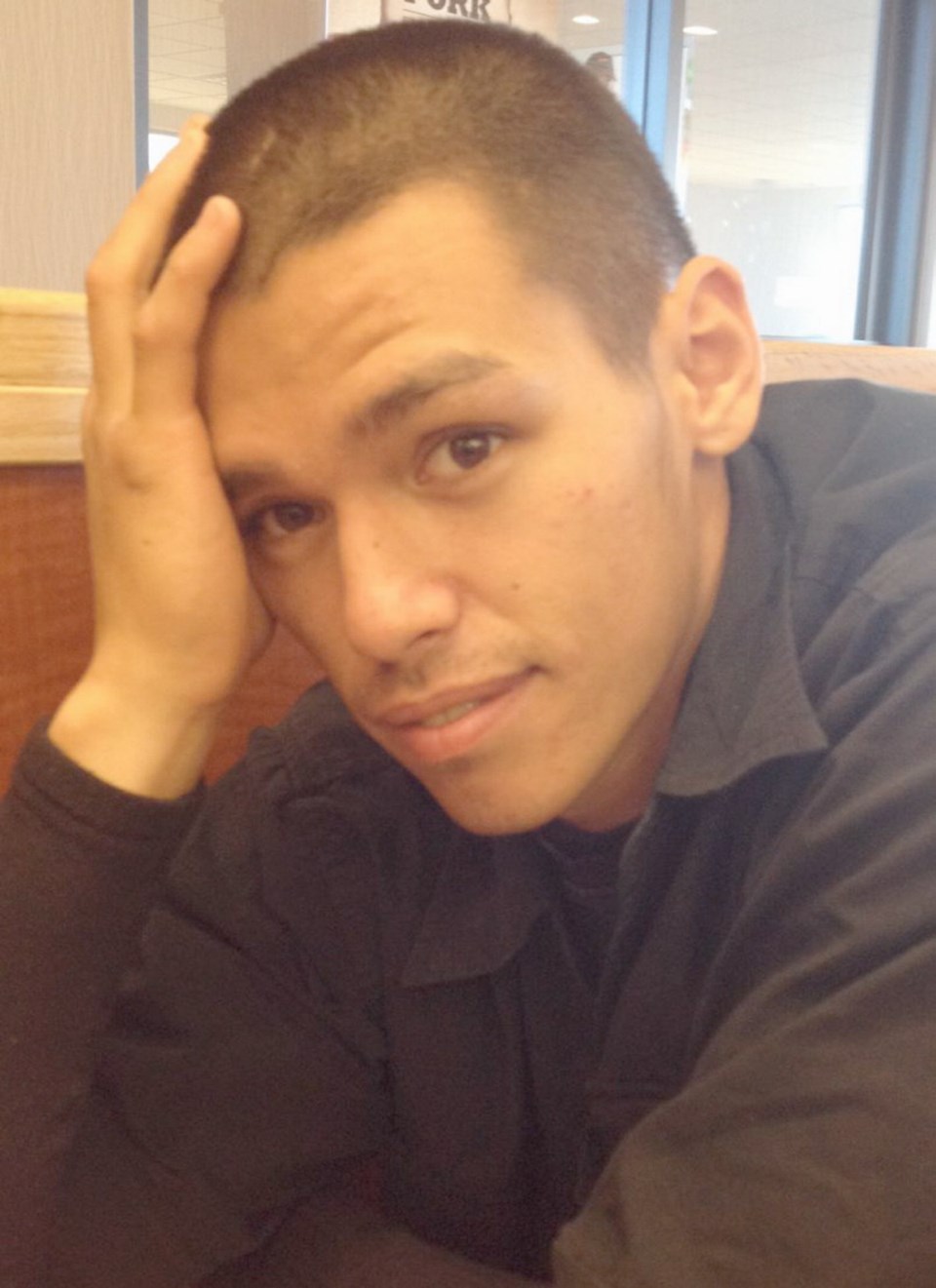

Twenty-four-year-old James Butters was shot five times by Port Hardy RCMP in 2015 and it took his family four years before they found out the name of the officer who killed him.

The officer was not named in the police watchdog report that cleared him of wrongdoing and found that Butters, also known as James Hayward, ran at him with a knife.

It wasn’t until the coroner’s inquest last year that the family learned that Sgt. Everett McLachlan had not completed his mandatory crisis and de-escalation training at the time of the shooting, said Butters’s aunt Nora Hayward.

It’s that lack of transparency around police use-of-force cases that Hayward — as well as lawyers and civil-liberty advocates — wants to change, as the provincial and federal government consider reforms to address systemic racism in Canada’s police forces.

“There isn’t enough accountability,” Hayward said. “Have [the officers] had issues before? It’s so hard for the public to find out.”

Protests around the world against anti-Black racism following the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed by a Minneapolis police officer, have pushed the U.S. and Canada to take action on racism in police forces.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s executive order to create a national database to track excessive use of force by police officers was decried as only a modest reform. But critics say B.C. is even further behind, as it’s nearly impossible to track an officer’s discipline record or use-of-force history except for rare instances where criminal charges are laid.

The Independent Investigations Office, B.C.’s civilian-led, independent agency that probes police-involved shootings or deaths, does not name officers being investigated. An officer is named only if Crown prosecutors lay criminal charges, which was the case this month when three officers, Const. Josh Grafton, Const. Wayne Connell and Const. Kyle Sharpe, were charged in connection with a violent arrest in Prince George on Feb. 18, 2016.

All three officers remain on active duty. B.C. RCMP spokeswoman Staff Sgt. Janelle Shoihet said “we are confident they can continue their duties in a manner that is safe and meets public expectation.”

Grafton, now a Nanaimo RCMP canine officer, is charged with assault, assault with a weapon and obstructing justice following a lengthy IIO investigation. Grafton was again investigated by the IIO after he punched a man twice in the face, fracturing the man’s eye socket and nose, following a two-hour chase through the snow in the mountains south of Nanaimo on Feb. 16, 2019.

The IIO did not release Grafton’s name in its final report, which cleared the canine officer of wrongdoing even though it found the force used was “at the upper end of the justifiable range.” Grafton was only identified because a Nanaimo RCMP media release shortly after the arrest named him as one of the canine officers involved.

The IIO’s chief civilian director, Ron MacDonald, said wording in the Police Act prohibits the naming of officers under investigation. If an officer has previously been investigated and cleared of wrongdoing in a case of serious harm or death, that previous investigation has no bearing on any other investigation involving the same officer, MacDonald said.

Victoria lawyer Richard Neary, who has represented both individuals injured by police and officers fighting discipline, has long been concerned about the lack of transparency and accountability in police-misconduct cases, saying “for every incident of police misconduct that comes to light, there’s dozens and dozens that go undiscovered.”

“The biggest flaw in the system is when misconduct actually does come to light in those rare instances, and [misconduct] is established, the consequences for officers are far too lenient and it makes it difficult for the public to have confidence in the process,” Neary said. “I think departments ought to be questioning themselves when they have a situation where the misconduct is confirmed and proven and fully established, yet the individual remains on the job.”

Neary said a public database of misconduct isn’t needed if an officer found guilty of misconduct is removed from the job.

Municipal police officers who are accused of misconduct, typically as a result of a public complaint, are investigated by their departments’ internal affairs section, unless the case is high profile enough to be handled by another police department.

The misconduct case is overseen by the Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner, which can order a public hearing if it does not agree with the finding of the discipline authority. Only in the case of a public hearing, presided over by a retired judge, would the officer’s name be made public.

“We do publish results of matters, but we don’t necessarily publish the names of individual officers, unless, of course, it’s a matter that ends up being public, like a public hearing or a review on the record,” said police complaint commissioner Clayton Pecknold, a former deputy chief of Central Saanich Police and the province’s former director of police services. “I do have the ability, in a case-by-case basis where it’s in the public interest, to put the information out there, but by and large, the [Police Act] legislation compels us to keep things like that confidential.”

Last year, a legislative committee looking into B.C.’s police complaint process recommended that the police complaint commissioner be able to call a review on the record earlier in the discipline process, but those changes have not been made to the Police Act.

It’s up to individual police departments to track and deal with officers who are the subject of multiple misconduct allegations or abuse-of-force allegations, Pecknold said.

Similarly, if RCMP officers are investigated for misconduct, their identities are protected by Privacy Act restrictions, unless the allegations go before a conduct dismissal hearing, which is public.

Esquimalt Mayor Barb Desjardins, co-chair of the Victoria and Esquimalt Police Board, questions the fairness of naming officers who are facing misconduct allegations, as many complaints turn out to be unfounded. The police board is notified when an officer is under investigation and is updated on the result. Desjardins said in the majority of cases, the officer is found to have done nothing wrong.

“Is it fair to present that information when nothing has been substantiated?” she said.

Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth has promised to move ahead with reforms to the 45-year-old Police Act. In the upcoming legislative session, Farnworth will table a motion to create an all-party committee that will talk to communities and experts on how the act “can be modernized to reflect today’s challenges and opportunities for delivering police services, with a specific focus on systemic racism,” he said in a statement.

However, amending the Police Act is not enough to eliminate systemic racism, which is embedded in every government institution, from health care to the criminal justice system to the school system, said University of Victoria professor Devi Mucina, program director in Indigenous governance.

Police departments do not collect information on race or ethnicity, which Mucina said makes it impossible to determine if people of certain races are being disproportionately targeted. A CBC investigation that tracked fatal police shootings between 2000 and 2017 showed Black and Indigenous people are disproportionately the victims.

“How can you claim to be serving diverse communities when there’s no mechanism to see how well you’re doing?” Mucina asked.

Pecknold said he’d like the power to investigate systemic causes of certain types of police misconduct, something recommended by the legislative committee into the police complaint process. The Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner does get complaints alleging a police officer was racist, either through words or actions, Pecknold said.

Meghan McDermott, a policy expert and lawyer with the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, said while there must be a balance between an officer’s privacy and accountability, there’s a compelling argument for naming officers facing misconduct or abuse-of-force allegations.

“We hear from families who have lost someone in a police shooting. The fact that they don’t even know the identity of the individual who pulled the driver and killed their brother or their child and the idea that this person is still out there on active duty or maybe they’re not, but they can’t find out either way, causes so much emotional distress to the families and the survivors.”

Who filed a complaint

Anyone who files a complaint against a police officer through the Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner is asked to voluntarily provide their age, gender and race/ethnicity. Based on data collected between April 1, 2019 and March 31, 2020, of the 75 per cent of complainants who provided their race or ethnicity, 55 per cent were Caucasian; 12 per cent were Indigenous; eight per cent were East Asian, seven per cent were South Asian; four per cent were Black; and four per cent were Middle Eastern.

Most complainants were between the ages of 25 and 44 and the OPCC received eight complaints from youth under the age of 17. Of the complainants who provided their gender, 37 per cent self-identified as female, 63 per cent as male and two per cent as transgender.