The date is April 2, 1898 and something odd has happened at the Caledonia grounds in Victoria.

The B.C. Intermediate Football Association’s Nanaimo Thistles are competing for a provincial championship in the finals against Victoria YMCA, but sickness has claimed two of their right-wingers.

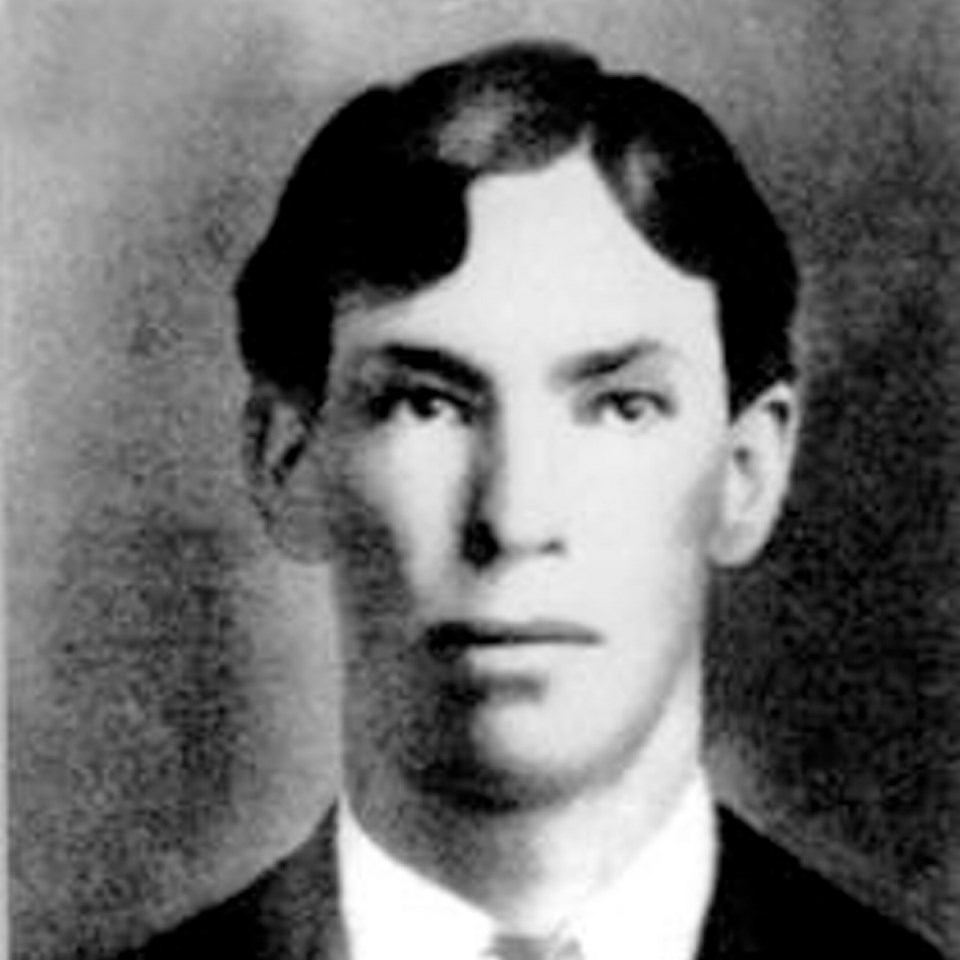

In a bid to save their shot at the Challenge Cup title, Nanaimo turns to two players from Snuneymuxw First Nation: James Wilks and Harry Manson.

The two become the first indigenous players to take part in a provincial championship match - playing alongside the whites.

Manson hits the field and finds himself in a back-and-forth match with YMCA.

Suddenly, he gains control of the ball and in perfect form, sends it flying into the net with a clean kick to open the scoring, a clear indication as to why the Thistles’ management has become so enamoured with the young star.

While Nanaimo storms out to a 2-0 lead, bolstered by the play of Manson, the team ultimately falls by a score of 4-3. They later lose the third match of the final series and see the Challenge Cup go to Victoria.

Nevertheless, a star is born.

During the years 1897-1904, Manson captained the Nanaimo Indian Wanderers to numerous victories, including a Nanaimo City Championship in 1904.

The year before, Manson had been selected from the Wanderers to play on a Nanaimo all-star team, and helped to lift the squad to a provincial championship.

Amid a climate of racial intolerance when public humiliation of indigenous people was not only commonplace, but socially acceptable, Manson broke barriers as a First Nations soccer star.

Manson’s accomplishments have impelled Vancouver-based soccer historian Robert Janning, 57, to lead a push to have the forgotten star inducted into not only the Nanaimo Sports Hall of Fame, but major sporting shrines across Canada.

“My hope is that somehow, if I can get Harry inducted into one of these sports hall of fames, something positive will ripple out of that and give the First Nations community a sense of pride and celebration,” said Janning. “That when school classes get invited to the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame, they can make a connection: ‘there’s an indigenous athlete there.’”

Janning’s re-discovery of Manson occurred while he worked on Westcoast Reign: The British Columbia Soccer Championships 1892-1905, an exhaustive history of footy’s roots in this province that took roughly six years to compile.

A curiosity about B.C. soccer’s origins had led Janning to the public library, only to find nothing on the topic.

“I quickly realized that if I wanted answers to the questions I had, that it was up to me to launch an investigation,” he said.

Janning began an intensive exploration of archived materials, old newspaper clippings and microfilms. He poured through university libraries and materials at the legislature in Victoria.

Throughout the endeavour, another curiosity began to develop at the sight of the Manson name, which seemed to keep popping up in the material.

“The Snuneymuxw became involved quite early on because of their proximity to the European population,” said Janning. “It was inevitable that the two alien cultures were going to have some form of social interaction. Soccer turned out to be one of those forms.”

What also became evident was the intolerance Manson and his fellow athletes faced, with crowds shouting them down as ‘savages’ when the men laced up and hit the field.

In hopes of having Manson recognized as a pioneer in B.C. sport, Janning has made the rounds with politicians to ask for their support to have him nominated.

He has written to Premier Christy Clark and met with Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson about the topic. Next on the list are Nanaimo Mayor John Ruttan and the Snuneymuxw band council.

But the effort also has another purpose: to correct what Janning believes is a historical injustice.

Manson was killed in 1912, run over by a train while on a trip into town to get medicine for his infant son.

That six-month-old boy went on to have eight children of his own, including Gary Manson, whose only account of his grandfather, until recently, was a coroners report on his death.

The harshly-worded document dismisses Manson as “a drunken Indian.”

Janning discovered newspaper clippings that painted a different picture and ultimately, found himself on Gary’s doorstep in search of information on his grandfather.

Gary and his grandfather share the same traditional name, Xulsimalt, a title that took on new significance for the Mansons when Janning arrived.

“It was kind of ugly how they portrayed him in the inquest,” said Gary. “I went looking for him, because I carried his name. That was the only document on him I found. I was kind of heartbroken, actually.”

The Manson family had seen soccer-related photos of their ancestor before, but never realized the extent of his involvement until they met Janning.

“History died with him, our connection to our ancestors,” said Gary. “I just can’t say thank-you enough to Robert Janning, the author of that book.”

Janning takes solace in knowing he has the backing of the Manson family to help him further his cause.

“I believe his contributions as a person, a representative of the aboriginal community, and a Canadian sporting pioneer warrant official recognition,” he wrote in a letter to numerous political leaders. “This would not only be a suitable tribute to the memory of Harry Manson, but also serve as a source of inspiration.”