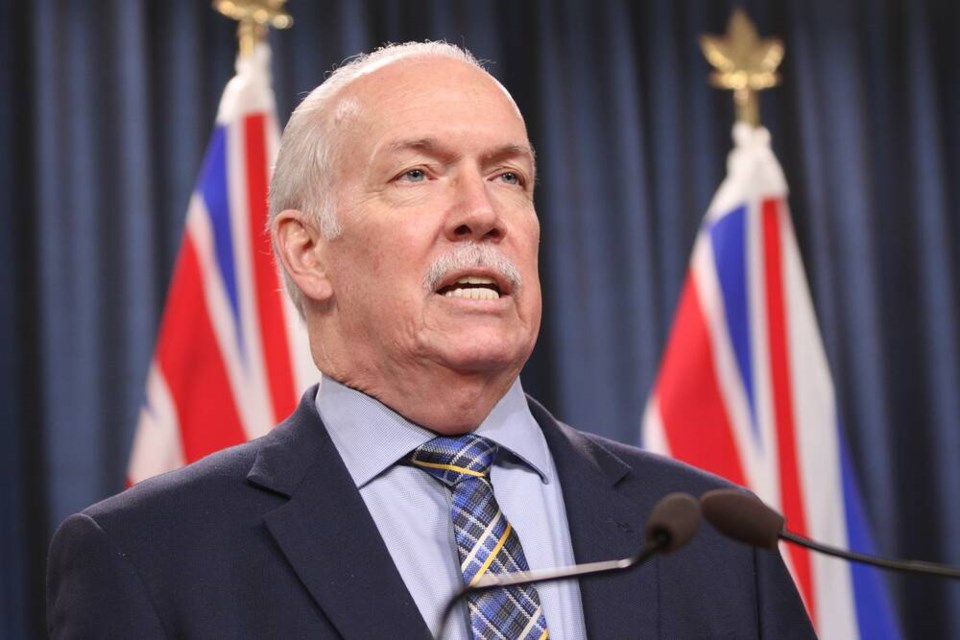

The prime minister has repeatedly said the best time to talk about health transfers to provinces is after the pandemic winds down, which means now, Premier John Horgan said in Saskatchewan on Friday.

“Well we’re here today, the pandemic is waning, it’s becoming endemic, and it’s time now to have that conversation,” said Horgan, who was attending Western Canada’s provincial and territorial leaders meeting in Regina. “I would hope today would be the beginning of that commitment to come sit with us.”

It’s the first in-person meeting for the western premiers since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and federal health transfers and post-COVID recovery are topping the agenda.

Last year, the premiers asked Ottawa for a $28 billion increase to health transfers, which would bring the federal share to 35 per cent from 22 per cent. At the 2021 premiers’ conference, attended virtually, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the goal is to increase the transfers, but the conversation would have to happen once the pandemic was over.

About 900,000 British Columbians are without a family doctor, including about 100,000 on the south Island, and a recent report by clinic directory service Medimap said Victoria had the longest waits in Canada for walk-in clinics. About four walk-in clinics have closed in the capital region since January, largely as a result of staffing issues. Interim funding of $3.46 million was allocated to keep another five open.

Urgent and Primary Care Centres have been built as part of a larger plan to address primary care needs, but they are understaffed. In the downtown Victoria UPCC, 45.66 full-time equivalent positions are funded but less than half — 21.61 — have been filled. At Nanaimo’s UPCC, 16.83 FTE positions are funded, but only 5.73 are staffed.

B.C. Liberal health critic Shirley Bond recently said in question period that fewer than two per cent of people who don’t have a doctor have been attached to one through UPCCs.

The province has about 6,800 trained family doctors, but only about 3,500 practise in that role, according to Family Doctors for Better Patient Care in B.C.

On Friday, Horgan blamed the primary-care crisis largely on insufficient federal funding.

“We have shortages of general practitioners because of challenges with funding. Is it just about money? Yeah, it’s about money, because the money translates into services for people.”

In Victoria, he said, “we have more 70-year-old doctors with panels of 80-year-old patients than anywhere else in the country.”

Horgan expressed frustration that although there has been plenty of discussion about getting to the table with the federal government over health transfers, “we’re not at the table.”

“Ottawa needs to get back in the game is to be full partners, and we’re not even asking for full partners — we’re asking for two-thirds partners in the delivery of what is the most important national program that we have.”

Horgan said he is in the unique position of not only seeing the health-care system challenges as premier but as a patient, having been diagnosed with throat cancer late last year and successfully completing radiation treatments.

The strain on B.C. health-care workers is “duplicated across the country,” said Horgan, adding for two years, Canadians looked to health-care workers to get through an extraordinary time. “And now is the time for us to turn back to the system and say: ‘We’re going to rejuvenate and we’re going to bring forward new initiatives on human resource development so we can have more care providers for the challenges of an aging population.

“We don’t need to wait any longer to do what the public expects of us.”

Horgan said as soon as B.C. gets a commitment of long-term, sustainable health funding from Ottawa, the province can “ensure that we’re creating the spaces, or training the next generation of health-care workers to deliver those services that people need.”

In addition to addressing surgical and diagnostic wait times that have grown during the pandemic, premiers want to see money go toward mental-health initiatives, tackling substance use and long-term care.

The federal government has signed agreements with many provinces to address those needs, but Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe, the meeting’s host, said it’s not viable in the long run. “We don’t know if that funding will be there two years, five years, seven years from now.”

Horgan, who broached the issue of federal health transfers with Trudeau while he was in B.C. earlier in the week, noted Friday that the underfunding of health care started long before the current federal and provincial governments.

The Council of the Federation, made up of the premiers of each of Canada’s provinces and territories, is scheduled to meet in Victoria July 11-12.

Horgan and Moe were joined in Regina by their counterparts from Alberta, Manitoba, Nunavut, Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

The premiers also plan to discuss economic recovery, energy security, labour and immigration.