Here, for Easter Sunday, is a story of death and, if not resurrection, then at least resolution.

Here, for Easter Sunday, is a story of death and, if not resurrection, then at least resolution.

It’s a tale of forensic science and human compassion combining to bring the remains of a long-lost son to his mother, half a continent away.

It’s about a John Doe who, after 18 years in a Saanich cemetery, was identified as a Washington state hunter who went missing in 1998.

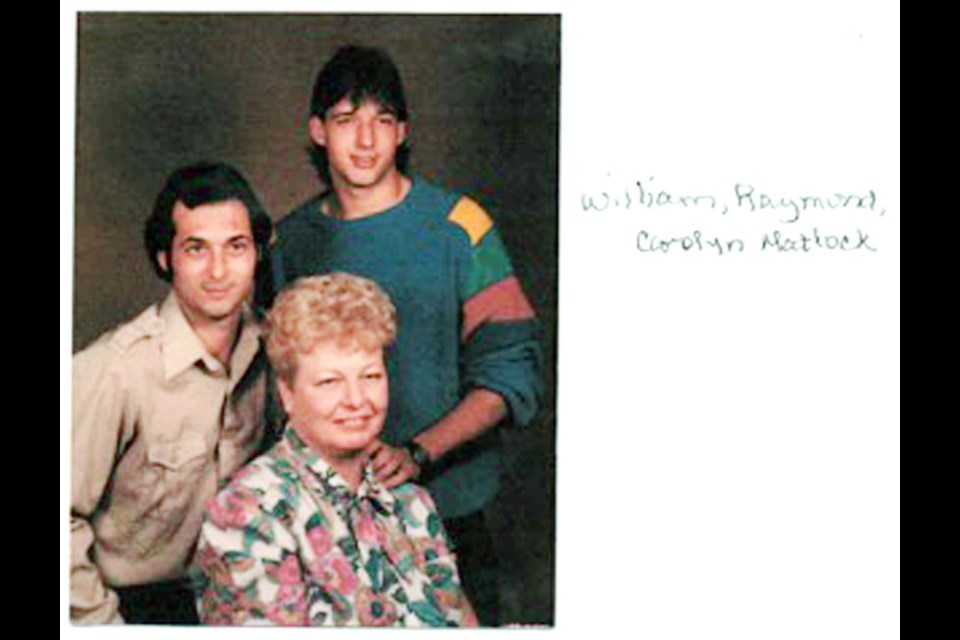

Raymond Lee Matlock, 28, was last seen near his home in Raymond, Washington, 50 kilometres north of the Oregon border, on Nov. 7, 1998. His two companions emerged from the bush in the nearby Bone River area saying he had disappeared while they were hunting elk.

An extensive search — the Pacific County sheriff’s office, dozens of volunteers, U.S. Coast Guard boats and helicopters — focused on an area of tidal mud flats, one that was described as extremely dangerous due to steep drop-offs into the river and feeder drainages. The search was called off after several days due to heavy rain, but resumed a month later with the help of cadaver dogs. Still nothing.

“The only thing they found was his hat,” says Raymond’s aunt, Marilyn Pettitt, on the phone from Georgetown, Texas.

That’s where Raymond’s mother, Carolyn Matlock, lives, too. Now in her 70s, she had raised Raymond mostly as a single mother. The disappearance of her son, who had moved to Washington from Texas to fulfil his dream of becoming a commercial fisherman, devastated her. “My life went into shock,” she wrote.

Carolyn’s grief was compounded when her other child, Raymond’s older brother, William, died in a car crash in 2007.

Not knowing Raymond’s fate was hard on his mother. “All these years, in the back of her mind was ‘he might be alive,’ ” Pettitt says.

No one knew it, but Raymond’s body had, in fact, been discovered on Dec. 3, 1998, off Vancouver Island — more than 200 kilometres from where he went missing.

It was spotted in the water five nautical miles from San Juan Point, near Port Renfrew, by people aboard an American vessel. They called the U.S. Coast Guard in Neah Bay, Washington, which retrieved the body and brought it to the Island, where the case fell to the Sooke RCMP.

A Times Colonist story from the time said there was no sign of foul play. It was impossible to take fingerprints, but police hoped the man’s T-shirt — it had a drawing of a truck and surfboards, plus the words “Jimmy Z” — might help identify him.

An exhaustive investigation, including two post-mortem exams, facial reconstruction and dental comparison to missing people, proved fruitless. One clue emerged: The man was missing a front tooth on the upper left side.

In May 1999, the Vancouver Province reported that an autopsy had found no signs of violence and no indication of disease, drugs or alcohol. Full body X-rays found no fractures. “A check with B.C. and U.S. police found no link with any person reported missing.”

So on May 26, 1999, the remains were interred in Saanich’s Royal Oak Burial Park, although the skull was kept elsewhere for possible use in making an identification. Documents listed the name as “Unknown Male 98-174-0199.” The date of death was entered as Nov. 19, 1998.

The thing is, in checking missing-persons cases from the U.S., no one looked at the hunter in southern Washington. Why would they? Bodies have been known to float across the Juan de Fuca Strait, and remains found near Sooke in 1985 turned out, seven years later, to be those of a woman who went missing from the Seattle waterfront, but the idea of someone coming all the way up the outer coast wasn’t even considered.

“It’s more than 200 kilometres that the body would have to travel in the open ocean,” Laura Yazedjian says. “We had no idea that he could have come from that far away.”

Yazedjian, an identification specialist with the B.C. Coroners Service, does this sort of sleuthing for a living. A forensic anthropologist by background, she had gained experience in Srebrenica, Bosnia, where more than 8,000 were massacred in 1995 during the Balkans war.

When she joined the coroners office in Burnaby, she inherited B.C.’s unidentified-remains cases. There are 175 of them, the oldest dating back to 1962 (“I’d love to solve that one”), the newest to December. Sometimes she has a full body to work with, sometimes just a bone.

Solving these riddles, bringing relief to the families, is rewarding.

“It’s incredibly satisfying. The favourite part of my job is being able to change the name in our system from ‘unidentified.’ ”

The big break in this story came in 2013 after the launch of canadasmissing.ca, the website of the National Centre for Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains. A member of the public saw similarities between the Port Renfrew file and the Raymond Matlock case on the U.S. NamUs site — including the missing tooth.

Proving the link meant doing a DNA comparison (something not readily available in 1998). The Surrey-based B.C. Police Missing Persons Centre spent months tracking down Carolyn Matlock, who provided a sample in 2015. Due to the limited biological material available — it’s hard getting DNA out of dry bone — it took much longer to build a useful profile from the stored skull.

On Dec. 21, 2016, the match was confirmed.

Last Wednesday, Yazedjian got to type out a coroner’s report with the name Raymond Lee Matlock. She concluded his death was an accident — drowning, with hypothermia a likely factor, after falling into a river fully clothed.

Way down in Texas, Raymond’s family is grateful.

“It’s just a relief,” Pettitt says. She notes that her sister, Carolyn, recently dreamed that Raymond was alive and hiding. “She at least knows now that she doesn’t have to dream that dream anymore.”

They’re grateful for something else, too. After discovering the identity of the man buried at Royal Oak Burial Park, Lorraine Fracy, the cemetery’s manager of client services, offered to place a headstone at his grave free of charge.

But no, Carolyn Matlock wanted her sons together — though the cost of making that happen was daunting. So the burial park and Pacific Coast Cremation combined to exhume the remains, cremate them and ship them to Texas at no cost. (At disinterment, it was found that Raymond’s remains were in a metal container with handles — perhaps an indication that he had been buried with the possibility of exhumation in mind.)

“I cannot say enough nice things about Lorraine and how she has handled this,” Pettitt says.

“To me, she’s an angel. She has handled this in such a compassionate manner.”

Pettitt thinks Carolyn will scatter the ashes beside the grave marker that Raymond already shares with his brother, William.

That’s a reminder that, ultimately, this isn’t a happy story. It’s about a mother who lost both her children.

But it isn’t as sad as it could have been, thanks to those who worked to bring that mother closure, and then to show her some humanity after that.

Marilyn Pettitt and her sister, Carolyn Matlock, sat down the other day to put their thoughts on paper, writing mostly about Raymond — “a good man and a good son.”

They ended, though, by writing about others.

“The family wants to express their appreciation and admiration to Laura Yazedjian … who began the search to locate Raymond’s family, and to Lorraine Fracy … who arranged the return of Raymond to his mother. We are forever indebted to you. Thank you and may God bless you.”