“Nobody wants to do funny anymore,” Jim Taylor would say, every time we talked. “They’re all so serious.”

“Nobody wants to do funny anymore,” Jim Taylor would say, every time we talked. “They’re all so serious.”

I would respond by furrowing my brow and nodding seriously and mutely, because I always got a little bashful around Taylor in the same way beer-league old-timers shuffle their skates and get tongue-tied when meeting Bobby Orr.

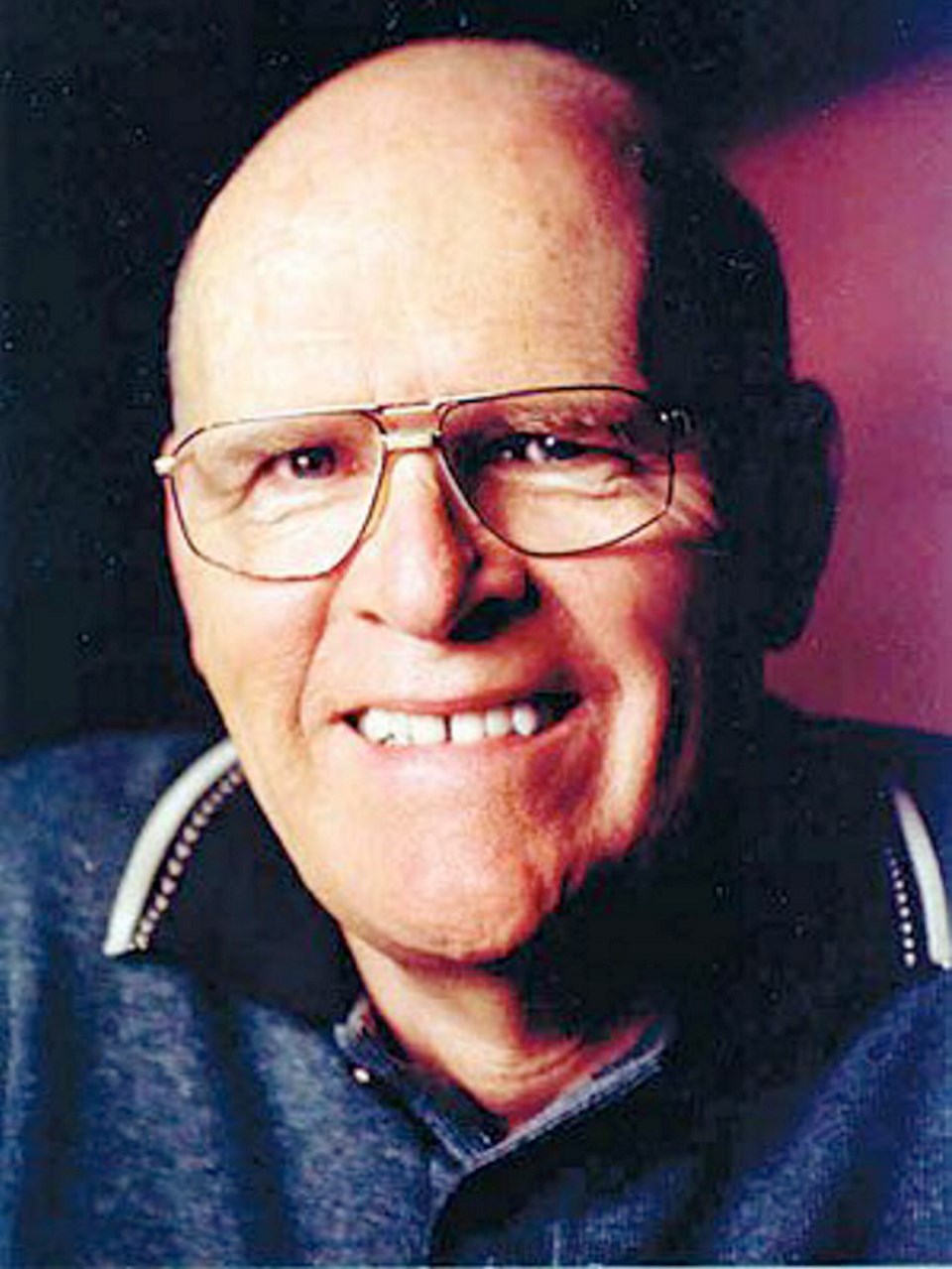

You might have heard by now that Taylor, the legendary B.C. sports columnist, died in his Shawnigan Lake home Monday at age 82. Cleve Dheensaw wrote a nice obituary in Tuesday’s TC.

I want to add my two cents worth today because Taylor, along with the Vancouver Province’s Eric Nicol, was the reason I first tried writing humour. And I will tell you this: He was always as nice and encouraging as could be. It’s good when your childhood heroes turn out to be the people you want them to be.

Taylor began writing for the Daily Colonist at age 17, even before graduating from Vic High in a 1955 class that also included future Olympic medalist and federal cabinet minister David Anderson, artist Fenwick Lansdowne and particle physicist Stew Smith. He had moved out from Winnipeg a year earlier with his mother, who ran the coffee shop at St. Joseph’s Hospital. His dad had died of cancer when Jim was seven.

The Colonist was a good place to learn. Once, when Taylor demanded to know why he had been forced to rewrite a story six times, mild-mannered colleague Doug Peden replied: “Because we think you can write, and we aren’t going to let you get away with doing anything but your best.”

After a decade at the Colonist and a short stint at the Times, he moved to Vancouver, where he became a must-read, and not just by sports fans. You didn’t have to be one of the latter to know “It’s Minor Hockey Week in Canada. Take a Canuck to lunch” is funny.

He covered the big stories, was in Moscow when Paul Henderson scored in 1972 (Taylor had a funny story about two Canadian players who unscrewed what they thought to be an electronic listening device hidden under a hotel carpet, only to hear the chandelier crash to the floor of the room below). When Mike Tyson was disqualified for biting Evander Holyfield, Taylor opened his column -- written on deadline in a near-riot at ringside — with this: “And so, after all the hype, it will go down as the first heavyweight title fight in history where one of the shots should have been tetanus and the champion won by an ear.”

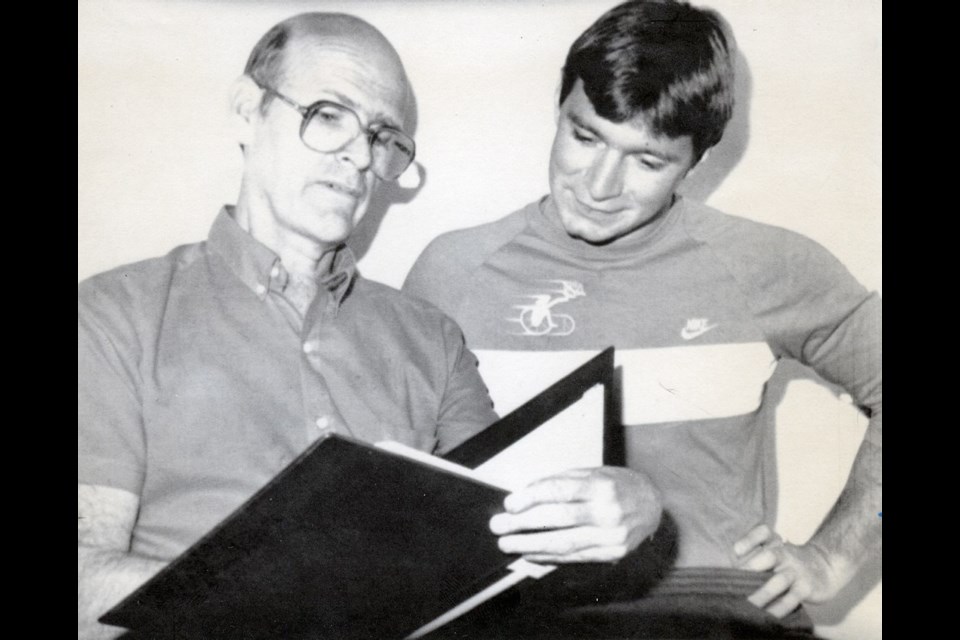

He was prolific. In addition to his columns, radio and TV work, he wrote 16 books (I know the number because he liked to remind me how many more he had published than I). They included Wayne Gretzky’s authorized biography and the story of Rick Hansen’s Man In Motion tour (as Hansen nervously wheeled to the start line on Day One, Taylor leaned into his ear and whispered: “Better finish. A book called Halfway Around the World by Wheelchair ain’t gonna sell shit”).

What many didn’t know was why Taylor worked so hard: He wanted to provide for his daughter Teresa, whom a 1976 skiing accident left in a wheelchair, permanently disabled. He wrote about that experience in a touching column that he allowed the TC to reproduce as it sought donations for the Times Colonist Christmas Fund in December 2017. His writing wasn’t always humorous (and even when it was, it was never fluff).

He was a pro, gave me the best piece of deadline-writing advice I ever heard: “Some days all you’ve got in you is garbage. Just give them the best garbage you’ve got.” Do the best job you can in the time you have.

Taylor says it was Nicol who passed the advice to him — not at the newspaper but beside the rain-soaked soccer fields where their eight-year-old sons played on the same team. Taylor would pick the older man’s brain. “I would go to school,” he once told me. “He taught me that it was OK to be funny.

“That’s my complaint with newspapers now: Nobody laughs anymore.”

Taylor did. That included laughing at himself. A couple of years ago, after I published my annual compilation of nasty notes from readers, he mailed me a copy of a cartoon that one of his critics had sent him: a penis with black horn-rimmed glasses, it looked remarkably like the photo that ran with his column.

If the cartoonist meant to offend, it backfired. A prickly sort with a fragile ego might have been wounded, but Taylor thought it was hilarious. The framed original hung proudly in his home office.

He’ll be missed.