Just in time for Canada’s 150th, here’s a surprise: We don’t really say “eh” that much.

Just in time for Canada’s 150th, here’s a surprise: We don’t really say “eh” that much.

“ ‘Eh’ is used relatively infrequently in Canadian English,” Derek Denis says.

Statistically, we’re far more likely to tack “you know” on the end of a sentence, and even more apt to add “right.”

But when we do say “eh,” we often use the word like no one else on Earth.

So says linguist Denis, hailed by the University of Victoria as an expert on the social meaning and history of the two-letter word we think of as quintessentially Canadian.

Denis has spent the past couple of years at UVic doing post-doctoral research into the homogeneity of Canadian English — the question of why we all talk alike from Ottawa to Victoria. In the U.S. or Britain, you can often tell where people are from by their dialects, but here you don’t know if Buddy was raised in Bella Bella, B.C., or Ball’s Falls, Ont., until you cheer the Canucks and he punches you in the nose.

The hypothesis is that the English used by the United Empire Loyalists who flooded southern Ontario during the American revolution simply migrated west with their descendants, dominating other influences.

As part of that research — a side project, really — Denis has been studying “eh.”

The first documented use of “eh” in Canada, in T.C. Haliburton’s 1836 book, The Clockmaker, intersects with another Canadian tradition, American-bashing: “You Yankees load your stomachs as a Devonshire man does his cart, as full as it can hold, and as fast as he can pitch it with a dung fork, and drive off; and then you complain that such a load of compost is too heavy for you. Dyspepsy, eh! infernal guzzling, you mean.”

Others used “eh” before us, though. The first recorded mention of the word was in Irish playwright Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer in 1773.

“We hear ‘eh’ in Englishes around the world,” Denis says. Britain, the U.S., Australia, South Africa. It’s even a bit of a stereotype in New Zealand, just like here in Canuckistan.

In most places, Canada included, “eh” is appended to sentences as a way to elicit a response from whomever we’re talking to: “The Leafs suck, eh?” Adding the word invites either agreement or dissent (though we should all agree that up until this year the Leafs have, in fact, sucked).

Canadians will also add “eh” to a statement of fact: “I got my haircut today, eh.” And only in Canada does the word serve a narrative function. “We essentially use ‘eh’ as a kind of verbal punctuation,” Denis says. I got in my truck, eh, to go to Tim Hortons, eh, for a double-double. “That’s not seeking any response at all.”

Maybe that kind of usage is why, in the 1950s, the word began to be associated with Canada.

The connection became cemented in the 1960s. By 1971, Time magazine reported that border guards were using “eh” as a shibboleth, a means of telling Canadians and Americans apart.

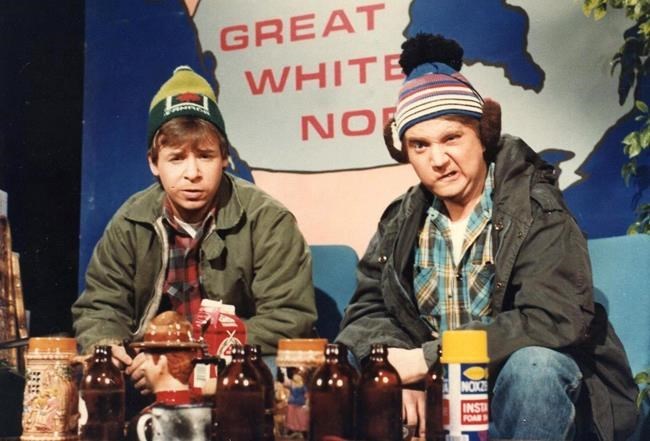

A major shift in the way we viewed the word came in the 1980s when SCTV made Bob and Doug McKenzie a cultural stereotype in both the U.S. and Canada.

There was a difference, though: Within the Great White North, Denis says, the McKenzie brothers mirrored a certain kind of Canajun, the doofuses from up the road.

But in the U.S. those tuqued-and-flannelled hosers with their two-fours of stubbies represented all Canadians.

This perception was not lost on us. “Canadians are quite aware of the negative stereotype held by Americans,” Denis wrote in a research paper.

“However, at the same time, NOT-BEING-AMERICAN is one of the main characteristics of Canadian identity.”

So we reappropriated “eh” as a way of setting ourselves apart. “Americans associate ‘eh’ with Canadian English,” Denis wrote. “Canadians do not want to be Americans. So therefore, ‘eh’ can be used ironically in expressions of Canadian identity, especially in contrast with Americans.”

We have commodified it, too: You can’t wander into a Government Street gift shop without seeing an eh-emblazoned T-shirt, fridge magnet or coffee mug. “We’ve taken ‘eh’ as a point of pride,’ ” Denis says.

We just don’t say it that often, right?