So, how did you react when you heard about the tsunami that wasn’t?

So, how did you react when you heard about the tsunami that wasn’t?

Did you call 911 to ask for advice? That’s precisely what you’re not supposed to do, but people did it anyway.

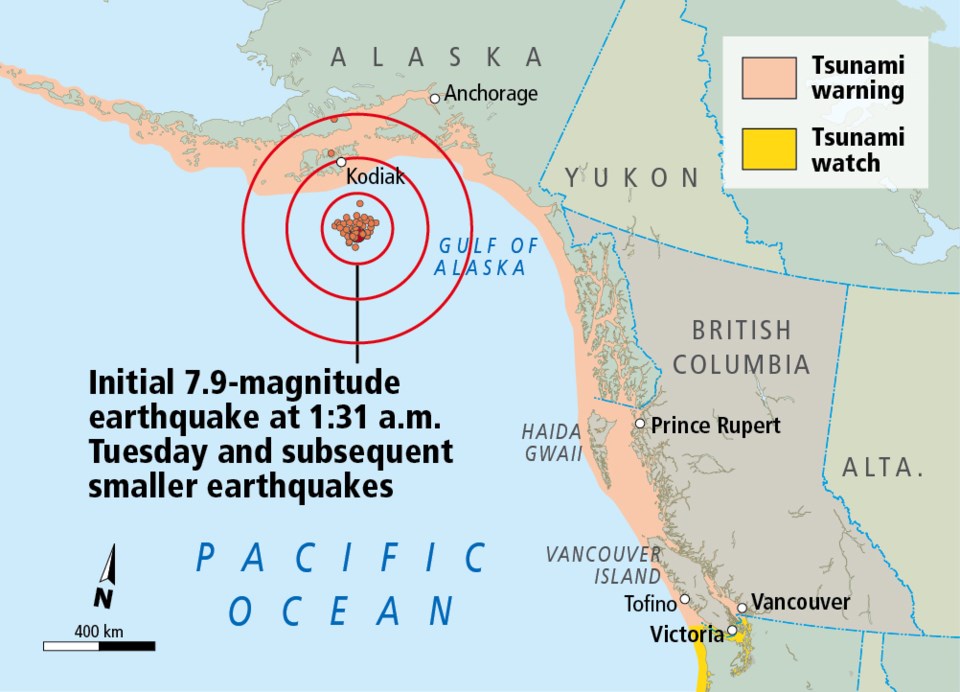

Between 1:52 a.m. and 4:30 a.m. Tuesday, VicPD fielded 76 calls to 911 and more than 200 to its non-emergency line.

That’s four times the normal volume. They had to call in three extra operators.

Did you ponder the dystopian nightmare rushing down the strait, take stock of your food supplies, and immediately go into survivalist mode? (Or, worse, start contemplating cannibalism? Remember the lyrics to that great B.C. folk song, I Ate My Fiancée: “She gave me heartache, she gave me heartburn, too.”)

Or did you do like Mary Coakley and decide to help your neighbours?

Coakley, who lives in a condo complex just paces from the Sooke River estuary, got a 2:50 a.m. call on her land line (who keeps a smartphone on at night?) from someone who had been alerted by an app on his own phone.

She groggily stuffed two knapsacks with cameras, hard drives, food and other bits she figured she’d not want to lose, and stumbled out the door.

Then she paused and looked up at the windows of her neighbours. Only one of 42 was illuminated. They were deaf to the danger.

What to do, pull the alarm? No, that would send fire trucks racing to a non-existent fire. Head for the hills and leave them sleeping? No, that felt wrong.

So, grimacing at the prospect of grouchy reactions, she decided to wake her neighbours, all of them. It took 27 minutes, running up and down three flights of stairs again and again, banging on doors. “My knuckles were quite sore,” she said.

As it turned out, no one was mad at her. Many had no plan for dealing with an emergency, though. Some didn’t have vehicles. Some were elderly and had limited mobility. Some, not knowing where to turn, simply decided to wish the threat away.

It would be easy to go tsk-tsk and chide their lack of preparation were it not for one thing: Most of us are in the same (leaky) boat. Oh sure, every time a minor earthquake sends the ground (and our knees) trembling, we promise to check the disaster insurance, to bolt the hot water tank to the wall, to anchor the bookshelves and to replenish/buy the emergency kit we always intended to have ready in case of The Big One. It’s a vow as fervently and temporarily sincere as the “Oh God, I’ll never drink again” prayer.

Yes, there was a bump in business Tuesday at Victoria’s Columbia Fire and Safety, people buying grab’n’go bags filled with the things you’ll need when disaster strikes: silver foil heat-preserving blankets, flashlights, work gloves, food that is dried and shrink-wrapped for a five-year shelf life.

But such spurts always tail off after the initial shake-up (as it were) recedes. “We are in a dangerous zone,” said Columbia’s Adam Skibo, “but we don’t like to think of it daily.”

Tuesday also saw a rush of interest in a variety of emergency-alert apps and social media accounts like @emergencyinfoBC on Twitter.

The City of Victoria said the number of people signed up to its Vic-Alert service jumped from 6,500 to more than 34,000 by mid-afternoon Tuesday. Vic-Alert provides emergency information by text, phone and email.

That’s great as it goes, but in a politically fragmented area like Greater Victoria, people were still uncertain where to turn for information Tuesday. Social media were full of stories of Vancouver Islanders who first learned of the tsunami threat from people abroad.

One of the things that became apparent was that while authorities were good at reaching people who might be in danger, those outside of the high-risk areas often found themselves in an information vacuum, not knowing whether they were in peril or where to turn to find out. Hence the calls to 911.

For those who didn’t sleep through the whole arc of the tsunami scare, it wasn’t always easy to know what to do.