Our joke is that Lindsay Wong and I are doppelgangers, because we aren’t.

She’s young, female, stylish, Asian, Ivy League-educated and a bunch of other things I am not. We crossed paths a couple of times last year when the Vancouver author was promoting her bestselling book The Woo Woo.

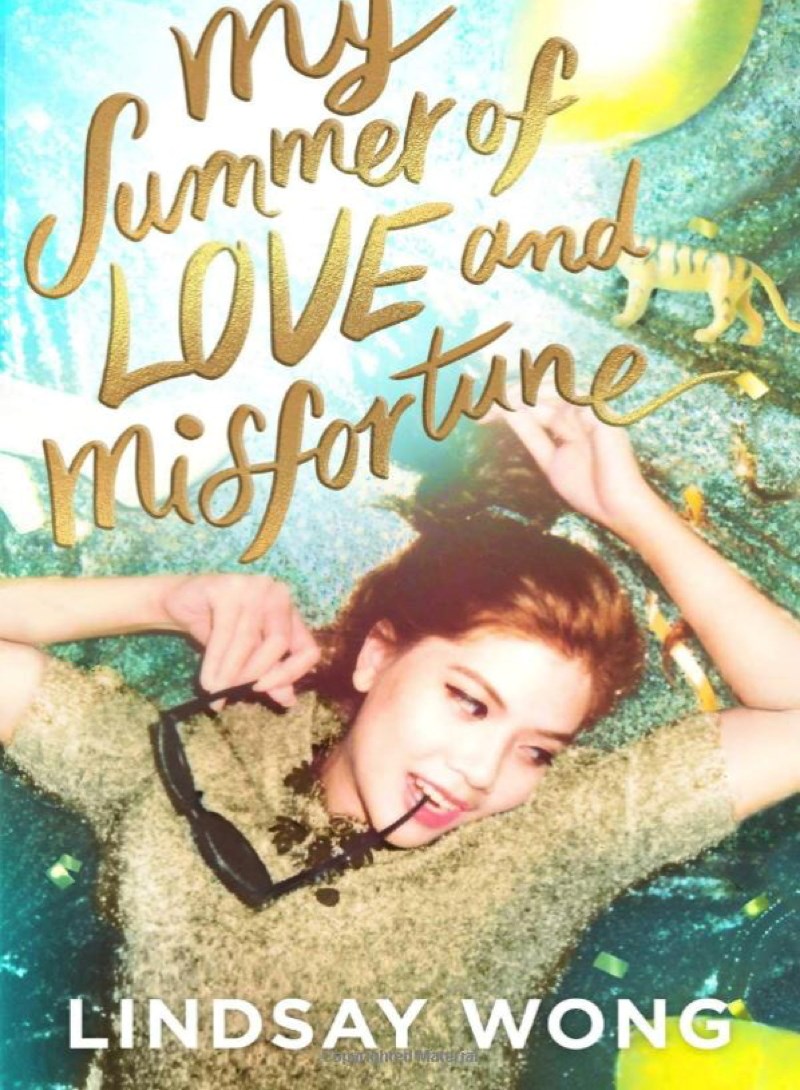

This week, she was supposed to be celebrating the launch of My Summer of Love and Misfortune, her new young adult novel. Instead, with our neighbours to the south embroiled in the fallout of George Floyd’s death, she put book promotion aside to keep the focus on what she said were more important conversations, ones about race.

That she was willing to do so, sacrificing her own interests, says a lot about how badly she thinks we need to have these discussions — and how important it is for people like me to be in the room.

Lindsay’s life experience is different from mine, which means our perspectives are different. Like three in four Canadians, I’m white — the national default setting — so seldom find myself in situations where my race comes up at all. Wong, on the other hand, never really gets to forget it.

So, while I spend my time fretting about whether the Canucks will be able to dump Loui Eriksson’s contract (really, it’s an anchor) she has to worry about stuff I never see, like guys acting inappropriately when they catch women of colour on their own. It has to do with a perception of vulnerability, she says.

Wong needs to be even more alert than usual these days, thanks to B.C.’s spike in anti-Asian racism. You probably read the stories — an old woman tripped in a park, an old man shoved out of a convenience store, people yelling “Go back to China!” — but when you did, you probably just shook your head in dismay and turned the page. Wong doesn’t have that luxury.

“I’m kind of frightened to take transit by myself,” she said Wednesday. Also, the other day, a man eating a sandwich on a Coquitlam bench hurled racist slurs at her when she passed too close for his liking; she was just one of those to walk through his comfort zone, but he saved his abuse for her.

These things can come out of the blue. One of the events where Wong and I crossed paths last year was on Denman Island, where author David Chariandy, who is of black and south Asian heritage, recalled an outing in which he and his three-year-old daughter happily tucked into a big slab of chocolate cake at a Vancouver eatery.

It was a lovely story, right up until the point where Chariandy got up to get a glass of water, only to be shouldered aside by a nicely dressed white woman, who declared: “I was born here, I belong here.” So much for the perfect daddy-daughter adventure.

Chariandy related this story not with anger but a sorrow that was a million times more painful. The incident became the genesis for his book I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You, in which he tried to gently prepare his daughter for life without taking away her sense of hope.

Think of that, then think of being on the Tseshaht reserve near Port Alberni one night this week when someone in a pickup truck trolled past making war whoops like those heard on an old Hollywood western. Think of being the target, of the implicit message. Aren’t we supposed to be past this?

Yes, but we aren’t. When essayist Scaachi Koul appeared at Sidney’s literary festival in 2017, she read a funny, sobering piece about growing up as a brown girl in Calgary, about casual (and not so casual) racism and about knowing her mixed-race but fair-skinned niece’s life “would be different than mine, because her race is a footnote instead of the title.”

Most people need not ever consider the advantages or disadvantages of race, whereas for others, it’s the lens through which they are viewed.

That’s the point. Most of us rarely have to think about race, so don’t. Or, like neighbours watching the cross-the-street house burning, we look at the U.S. and thank God it’s not us — though this requires a narrow definition of “us.”

We all need to look beyond our own experience, to be there for one another, to treat each other as we would hope to be treated. We all, like Lindsay Wong, need to make room for the conversation, if only to listen.