On a dark and rainy November night almost 19 years ago, Greater Victoria lost its innocence.

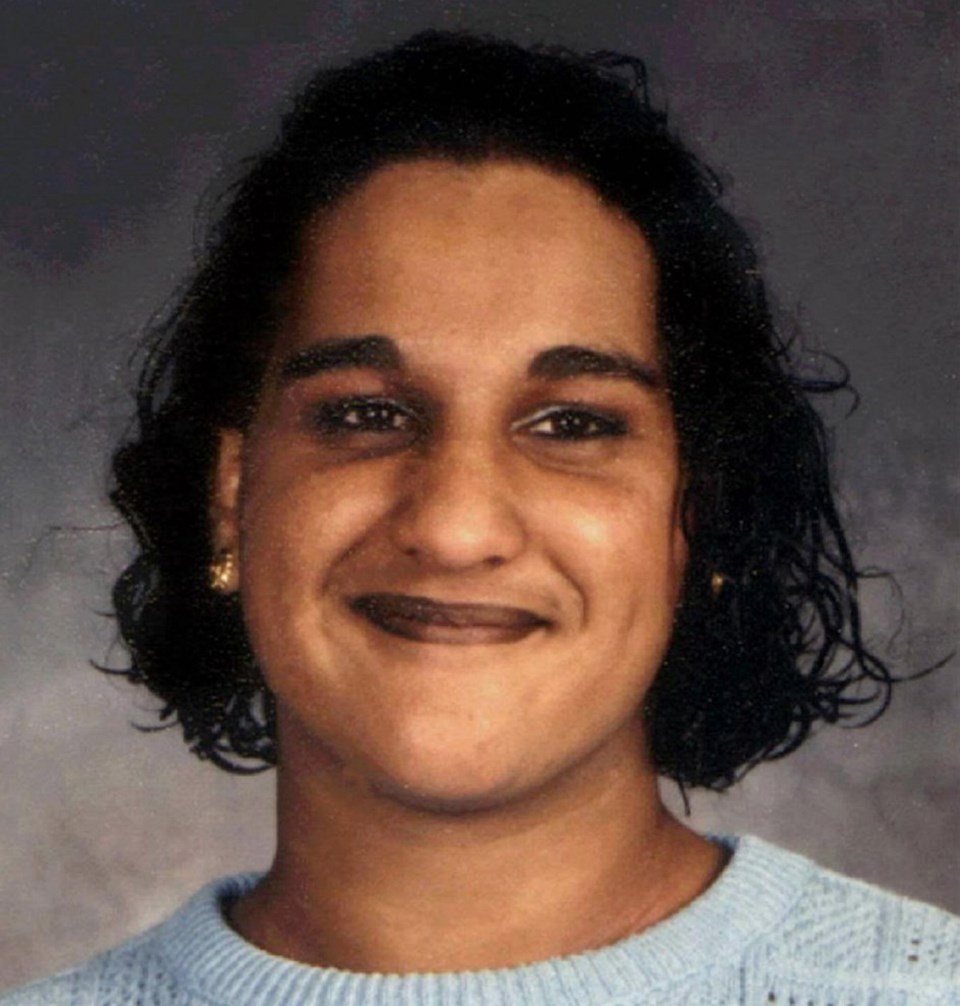

The murder of 14-year-old Reena Virk at the hands of her peers was a watershed event that changed people’s attitudes about youth violence, retired Victoria police Sgt. Rob Dibden said Tuesday.

The officer, then an Esquimalt police constable, was part of a team of investigators who heard rumours about an assault and murder of a missing teenage girl.

“It was shocking to realize what had actually happened,” Dibden said.

“It took us a few days to realize what had actually occurred. And as that was unfolding, every time new information came to light, it opened your eyes a little wider and it was shocking. Even as police officers, I think most of us were taken aback by the savagery of it and the absolute senselessness of it.”

Reena’s murder put Victoria on the international map in a very negative way, Dibden said. Six girls were convicted of assault causing bodily harm to Reena and sentenced to up to one year in custody. Warren Glowatski and Kelly Ellard were convicted of second-degree murder.

Dibden said he had mixed feelings about whether Ellard, now 33, should be released on day parole.

“I have a certain amount of faith in our criminal justice system. I think those decisions are made for the right reasons and I’m hoping in this case, it will be true, too.”

Former Esquimalt police Const. Tom Woods, who had just helped launch an anti-bullying program when the attack happened, said he was personally affected by the case.

“We all were,” he said. “I don’t think there was one police officer working at the time who wasn’t shaken to their core. It’s one of those things where you think: ‘What if?’

“Many people who worked with students at the time got a wake-up call that we need to pay really close attention to what’s happening with our kids.”

Woods and four other officers had given two pilot presentations of their anti-bullying program Rock Solid at Esquimalt High School, when the murder drew international attention, prompting interview requests from media such as the New York Times.

“The interactive presentation really caught fire. We travelled all over Canada, did an Arctic tour and visited just about every province. We estimate we spoke to close to a million students over several years,” Woods said.

The message was that coming forward with knowledge of bullying doesn’t make you a rat.

Rock Solid was replaced by WITS, which targets kindergarten to Grade 3 students and has been presented to more than 300 elementary schools.

NDP MLA Carole James was chairwoman of the Greater Victoria School Board at the time. She remembers how the community pulled together during the tragedy.

A media horde swarmed the Craigflower Bridge, trying to get students to talk to them about what had happened, she said.

“It was an awful time for everyone,” James recalled. “We had the tabloids here. They were bribing students with cigarettes to come and talk to them.”

The reaction of many parents was to close their doors, keep their kids at home and try to protect them as much as they could.

“I remember having a conversation with parents about the strength we had to have by being out in the community and that locking your doors was the worst thing we could do.”

Over the years, James has been struck by the different ways Ellard and Glowatski have dealt with the situation.

Glowatski went through an extraordinary restorative justice program with Reena’s parents, Suman and Manjit Virk, and was given full parole in 2010, James said.

“To witness, in what was a horrific situation, the bravery of the family to come forward and go through a process like that is amazing,” James said.

“Also, that Warren sat across from them and took full responsibility. It was a very powerful thing and pushes the support we need for restorative justice program.

“It was incredibly moving to see how it provided a different kind of closure for all of them. And Kelly Ellard is still in prison.”