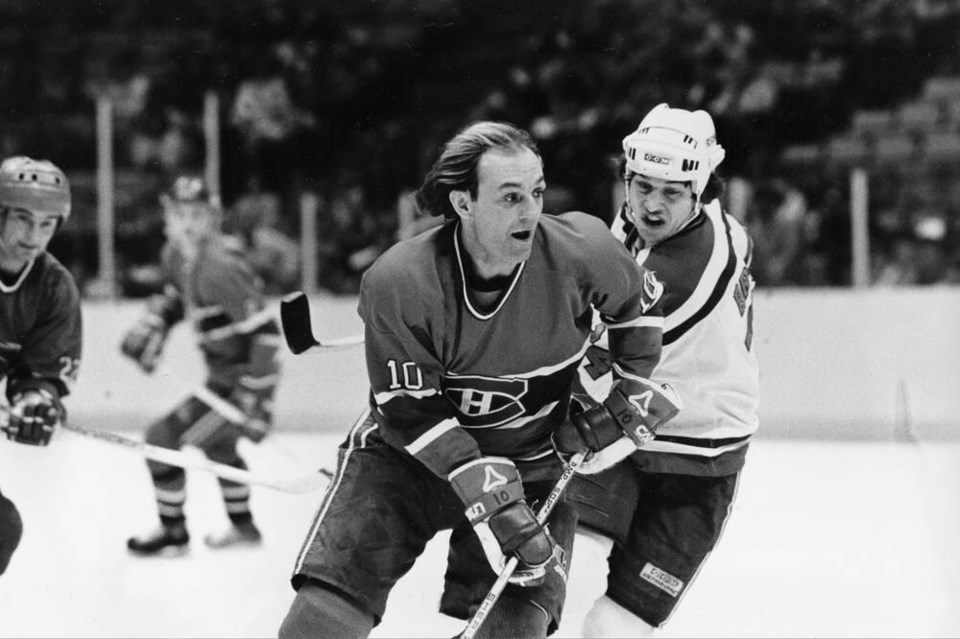

I once bought a Montreal Canadiens sweater with the number 15 on it, because even in my driveway dreams I wasn’t good enough to wear Guy Lafleur’s number 10.

Nobody was. In the 1970s, Lafleur’s halo was as golden as the hair that flowed behind him as he flew down the ice. Pure poetry.

That hair might have thinned and greyed before he died of cancer this week, but in his day he was Nureyev on ice — not that we knew or cared who Nureyev played for. Guy was the guy who skated into our living rooms on Saturday nights.

That last bit was important. Lafleur was a shared experience from coast to coast, largely because of the technology of the time. He arrived in the 1970s, during a period in which mass media was advanced enough to reach almost every corner of the country, but not so advanced that our attention was fragmented by the billions of choices we have today.

The result was that from Victoria, B.C., to Victoria, Newfoundland (yes, there is such a place, by Conception Bay) we all read the same stories, watched the same shows. There was just one Hockey Night In Canada game on TV, and chances are that it featured either the Canadiens or Toronto Maple Leafs — and only Montreal had Lafleur, all flash and flair and lift-you-out-of-your-seat excitement. Other players — Marcel Dionne, Gilbert Perreault, the still-great Bobby Orr — were electric, too, but they were out of sight down in the U.S., which to Canadian viewers might as well have been Guam. Lafleur was the one we had in common.

Or maybe that’s overstating the case, viewing Lafleur’s impact through a narrow lens. Baby boomers tend to act as though history began with the assassination of JFK and ended with the murder of John Lennon, with those falling outside those brackets not counting as much. In reality, every generation has its fallen idols, the ones it grieves like family but who are unlamented by others. Kobe Bryant. Marilyn Monroe. Prince. Princess Diana. Belushi. Churchill. My father-in-law mourned Elvis, who meant nothing to me.

Around the end of 1994, I read a survey in which news editors were asked to identify the most underplayed story of the year, the one that they hadn’t given the attention it merited. Their top answer: the death of Kurt Cobain. In making that choice, the people running the newsrooms admitted they hadn’t recognized what the Nirvana singer meant to his cohort. Had it been Paul McCartney or Mick Jagger who died, the story would have topped the broadcasts and been on the front of every newspaper. (For the record, the Times Colonist ran the story of Cobain’s suicide on the third page of the entertainment section; the first was dominated by a feature on folkie-activist Bruce Cockburn.)

The bias wasn’t just against the young. The same decision-makers would also miss the significance when a used-to-be-consequential figure of the past departed. That’s when a grey-haired higher-up would demand an obituary, a task that a younger editor would grudgingly assign to a fresh-faced intern who would desperately cobble together a piece that, while factually accurate, would have about a 30-per-cent chance of conveying why anyone should care.

That’s how disconnected we were. That’s how disconnected we still are. Actually, the gaps are more pronounced now, because the chances of us being drawn together by shared experiences have diminished. We no longer live in households with just two TV channels, one of which is showing Guy Lafleur. We no longer live in nascent-internet Nirvana times. Even within generations commonality has diminished. Today’s fans can, at their leisure, choose between Auston Matthews, Connor McJesus or the stars of professional tag (yes, it’s a thing) without crossing paths.

That’s also the way we consume information. We choose from a vast smorgasbord of sources, mostly gravitating to ones that reflect our own opinions. Our silos become echo chambers. Everyone looks at the world through their own lens without consideration of what the view might look like from another perspective.

Sharing common experiences helps bridge those gaps. And really, you haven’t truly lived until you have experienced the joy — or horror, for a Bruins fan — of seeing Guy Lafleur take a drop pass from Jacques Lemaire and tie Game Seven with 74 seconds left on the clock. Google it. Poetry for a generation.