Apart from the astonishing resumé, the dramatic historical moments he created and the immense reputation he developed, I flashed back on one thing when word of Ted Hughes’ death broke.

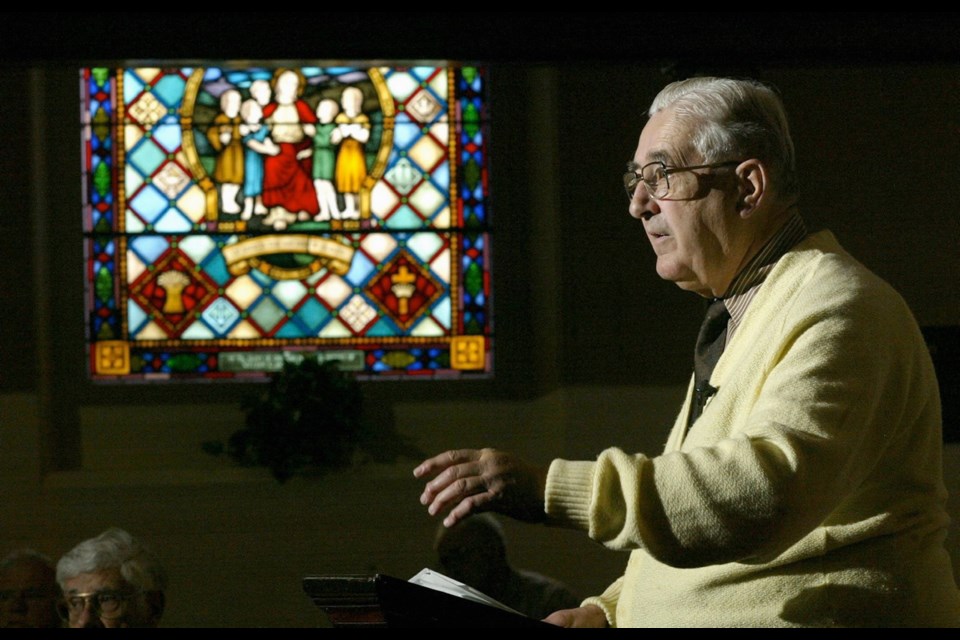

His eyes. He had a captivating gaze. It was avuncular and gentle for the most part, to the point where I once stopped in mid-interview and realized I was pouring my heart out to him when it was supposed to be the other way around.

But at the same time, it was sharply inquisitive. The eyebrows would cock up slightly and you’d realize he kept a degree of skepticism at hand about most of what passed his way. Like they say in international negotiations: trust but verify.

They could also flash angrily, like when he recounted repulsive details from the hearings he adjudicated into negotiated compensation for some of the residential school survivors. It takes a special inner strength to retain your faith in human nature while spending two full years listening to molestation victims pour out their hearts.

But mostly his gaze reflected a slightly detached amusement. He maintained a sense of humour while handling a long succession of white-hot, excruciatingly-sensitive political dilemmas, controversies and scandals with exquisite grace and sound judgment.

He first came to prominence in B.C. when some political stupidity in the Bill Vander Zalm government about one of the premier’s personal real estate deals escalated into a serious scandal.

In my memory, there was a period as that story rolled out when the whole political-legal system ground to an uncertain halt and there was no apparent way out of the mess. There was no template to follow, the role of conflict of interest commissioner hadn’t been invented yet.

Hughes walked into the rat’s nest — at the premier’s invitation — and came out with a concise, authoritative report declaring the premier was in a conflict of interest. Vander Zalm quit days later and order was restored to the workings of government.

Hughes became an arbiter of tough calls after that, and created the conflict of interest office that stands today.

He was the one umpire who never got booed, because everyone respected him so much. He did conflict-of-interest cases, police misconduct, justice reform and other hot potatoes here and elsewhere. As deputy attorney general, he once told his own boss he had no option but to resign.

The minister did just that.

When B.C.’s child welfare system came up short on some grotesque cases of neglect, the government turned to Hughes to tear it apart and put it together again. Then he rode herd on the government to make sure it stuck to his plan. The Office of the Representative for Children and Youth is entirely Hughes’ creation.

His B.C. career is a model of resilience, because it’s a story of bouncing back from adversity.

He was a senior judge in Saskatchewan but as biographer Craig McInnes recounted in The Mighty Hughes — office politics there turned toxic and he and Helen, his equally-legendary wife, bolted for the coast.

Their loss was our immeasurable gain.

Take pen and paper and make three columns: Canada, B.C. and Victoria.

If you note Hughes’ accomplishments under each heading, the listings are nothing short of amazing.

There are a lot of smart people in the upper echelons of government. But there has never been one who combined a keen intelligence with an innate sagacity to greater effect than Ted. And there’s never been one with the guts to use those traits to set the course on occasions when no one else was quite sure what to do.