I covered the last few months of Bill Bennett’s term as premier.

Proximity to power was still intoxicating back then. It was a distinct rush to walk down the hallway with him, or interview him. A bigger rush to go home and drop his name in conversations. “I was talking to Bennett yesterday,” I’d say, hoping for maximum impact, but usually get eye rolls.

It was a brief time that ended soon after he called a news conference on short notice and announced on May 22, 1986, he was quitting, after almost 11 years as premier. I kicked myself for years afterward because I’d had the impression he was due to check out. Should have floated a spec piece about that possibility, but passed.

He’d built his reputation by that point. That history, and my own limited observations, add up to one conclusion: Bennett, who died Thursday, was tough as nails.

There are various ways to climb to the top of the heap in politics, but the two main routes are based in either trying to be liked, or being respected. If you can straddle both, you’re gold. Popularity is the easier route, if it comes naturally.

Bennett would have finished well down the list in any popularity contest.

He made his name and his place in history, mostly by being respected.

If being respected carries a connotation of being feared, and inspiring wariness, then the description fits even better. He was respected for being a tough SOB who wasn’t afraid to set unpopular targets and steer directly for them.

The people closest to him idolized him, which can be read as an indicator of character.

I don’t recall anyone from his inner circle who ever broke ranks and started taking shots at him.

He was an extremely fit tennis nut, accomplished needler, and private wisecracker.

Favourite line to my predecessor and mentor, Jim Hume: “Hi Jim. Are you still writing for the newspaper?”

His political opponents loathed him and some still do. The public wasn’t nearly as warmly inclined as those closest were.

I don’t think most voters through the 1980s would say they really liked Bennett.

Which makes his winning record all the more impressive.

He won three elections in a row and it took 28 years before anyone else (Gordon Campbell) matched that.

He got into politics to avenge the defeat of his father, W.A.C. Bennett, by taking over his seat and his party. You’d need a psychiatrist to figure out all the emotional baggage he carried into the legislature, with that kind of back story. As a rookie MLA and leader, he was dreadful. But he learned quickly. I suspect the big lesson he learned was to stop trying to be liked. Just settle for being respected.

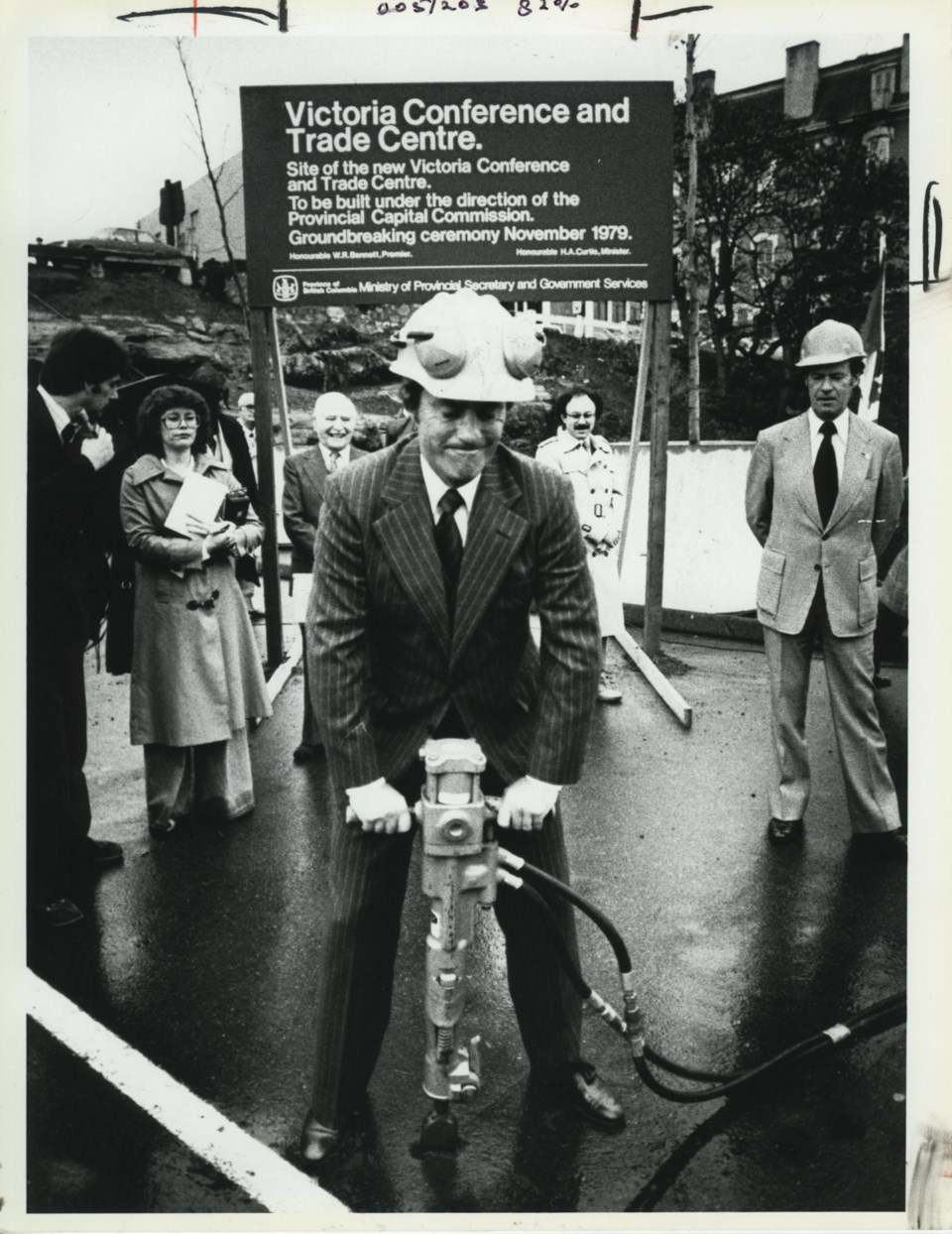

He won the 1979 election and started out building. Former deputy and biographer Bob Plecas calls him the father of modern government. He invented the Treasury Board in B.C, started the ombudsperson office and the auditor general.

B.C.’s potential with the Pacific Rim is a hackneyed political phrase these days. But it’s because people have been copying Bennett’s vision in that regard for 40 years. He opened trade offices and started the practice of regular visits and trade missions.

But his gutsiest calls were later on. In the face of a severe recession, he served notice he would scale back public spending.

Plecas recalled the impetus for the restraint program as simply this: When Bennett learned 40 per cent of forest industry was laid off, he decided that “if they were going to suffer, government was going to have to suffer.”

It stemmed from the basic conviction that government should always live within its means. Plus, he was naturally tight-fisted.

People had a fair idea of how tight government was going to get by 1983 and they still voted for him. When the full impact became clear, he faced down the uprising, and carried on.

At the same time, he pressed on with a full-scale commitment to Expo 86. It became a fabulous success that any British Columbian over 30 remembers. The Coquihalla Highway and SkyTrain were part of the deal.

He had the good sense to quit while he was ahead.

He was one of the greats.