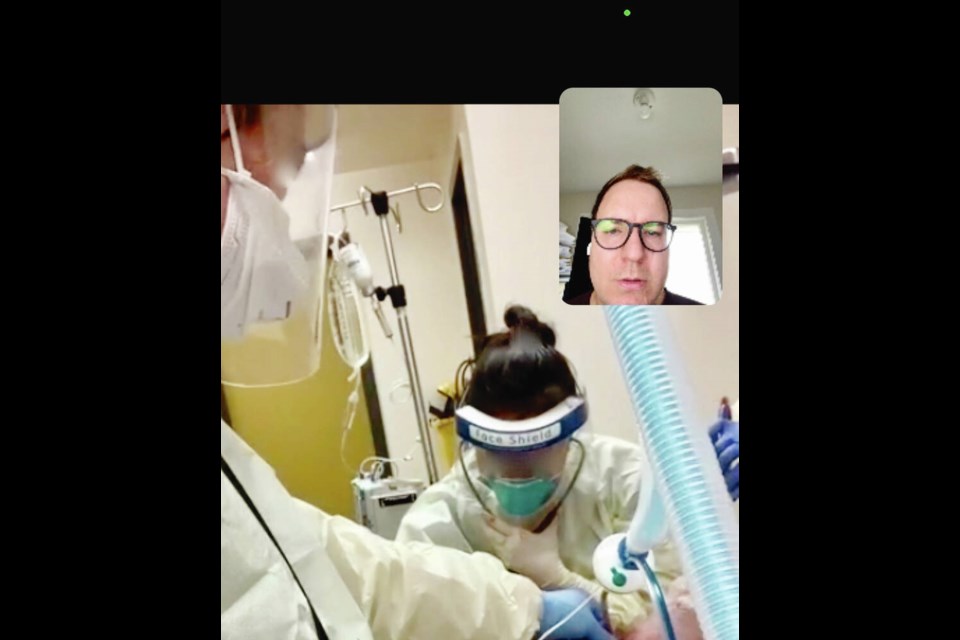

With minutes to save the life of a COVID-19 patient, a family doctor in northern B.C., directed by a specialist in Victoria via a video call, slices his scalpel into the patient’s neck and, while blinded by the spray of blood, inserts a breathing tube.

Dr. Adam Thomas, 36, peering over the family doctor’s shoulder online via an iPad, says it’s equal parts terrifying, frustrating and gratifying to guide a colleague through a critical procedure to save a patient’s life.

When the airway was punctured, the blood spray fully obscured the northern doctor’s face shield, Thomas said of the procedure. “I just had to coach them through. It’s a trust game between them and I, because I have to tell them about landmarks in the throat that they will be able to feel but can’t see.”

Thomas, an emergency and intensive-care physician in Victoria, is one of seven specialists in B.C.’s major centres — including Victoria, Burnaby and Abbotsford — who make up the Rural Outreach Support group, called ROSe for short, which provides real-time critical-care support online or by phone to physicians in rural and remote areas of the province.

The doctors say funding and involvement of intensive-care physicians in the program are under threat at a time when family doctors and nurses in remote communities continue to receive COVID pneumonia patients in need of immediate interventions, in addition to everyday patient emergencies. Thomas said the program is on “a knife’s edge and ready to fall apart,” although Health Minister Adrian Dix has downplayed those concerns.

The Health Ministry told the Times Colonist that funding for the program remains in place, with no changes anticipated, but further input would have to come from program lead Dr. John Pawlovich, who has not been available for an interview.

Victoria ER and ICU specialist Dr. Omar Ahmad said the ICU doctors in the program have been told they will be “transitioned” and will have to reapply for their jobs for reasons that haven’t been explained. “It’s been clear in communications verbally we will all be terminated.”

If that happens, it would be a huge loss, doctors say.

It was on a recent 12-hour ROSe shift that Thomas received the 2 a.m. call from a remote northern B.C. community about the COVID patient who ended up having the emergency airway procedure. Over the next 10 hours, he would oversee multiple procedures — some failed and some successful — a lot of waiting and a battery of calls to multiple hospitals and critical-care physicians to find the patient a bed. (We are not naming the doctor or community to protect the patient’s privacy.)

It was hoped the critically ill COVID patient could be safely flown south in the morning, when more than one air crew was available, but as night turned to morning, the patient’s condition declined and it soon became clear more was going to have to be done.

When a patient’s lungs are failing, the heart continues to spin out blood, but without the ability to put oxygen back into that blood, organs can start to fail, the heart slows, and the patient eventually goes into cardiac arrest.

By morning, the patient needed to be intubated to allow a ventilator to take over his lung function.

“It’s very scary doing it electively for surgery — when a patient has fasted, their medications have been optimized, and their oxygen saturation is 100 per cent — but in these emergent and semi-emergent situations that we do every day around the province and around the world amid COVID, they don’t always go that well,” Thomas says.

The family doctor tried to intubate the patient three times, but was unsuccessful. Attempts were made to suction blood out of the lungs.

Thomas then yelled over the iPad “failed airway,” signalling to health-care workers: “The patient will die unless we can get air in.”

When a patient’s oxygen is down at about 60 per cent “there’s very little wiggle room,” said Thomas.

The only option was to perform what physicians call a front-of-neck access or emergency cricothyroidostomy, in which a vertical incision is made to establish an airway.

It’s a Hail Mary cut to restore breathing so the patient can be transported to a larger hospital for the more complicated tracheostomy.

The rural family doctor had never performed it, so Thomas directed the team to gather sterile gloves, a scalpel and a Bougie — a long plastic stick to help deliver a breathing tube. In the end, the procedure was a success.

“They did an excellent job,” said Thomas. The patient was stabilized by noon and flown to Royal Jubilee Hospital, the only hospital that could accommodate them. “It was intense. All of us are so burned out.”

The Real-Time Virtual Supports program is funded through the province’s Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues, which aims to enhance physician availability in rural and remote areas of the province. Established in 2001, the committee is composed of the Doctors of B.C. — the physicians’ professional association, formerly the B.C. Medical Association — the Health Ministry and health authorities, and provides oversight to the Rural Co-ordination Centre of B.C.

While everyone from intensive-care doctors to pediatricians, labour and delivery specialists and dermatologists can be enlisted to help physicians in remote areas by phone or video, the bulk of the rural work is in the emergency and family physician stream, called RUDi for Rural Urgent Doctors in-aid, while the ROSe program has fewer physicians handling more complex cases.

As an ER doctor, Thomas said, “we know the first five minutes of every disease” and can perform life-saving procedures and stabilize patients, but it’s the ICU specialist who will take the patient who presented at the ER with spiking blood pressure, for example, and treat subsequent bleeding on the brain.

“The whole point is when resources are tight, how do we get those resources to very rural and remote communities —sometimes towns with just 600 people and a nurse practitioner, or a couple of thousand people with just one locum family physician?” Thomas said.

Under the ROSe program, physicians like Thomas receive a stipend of about $25 an hour or $300 for a 12-hour on-call shift, during which they can assist on everything from cardiac arrests to sepsis, overdoses and COVID pneumonia. They must have their mobile devices with them and remain in places that provide strong wireless internet and privacy for confidential calls that can last hours at a time. Each doctor works eight to 10 shifts a month.

The RUDi doctors, meanwhile, are paid $160 an hour, say the ICU doctors — an inequity that is causing problems.

Ahmad, who mentored Thomas, said he was at an ICU conference in Whistler in 2013 with Dr. Don Burke, a critical care and infectious disease specialist at Abbotsford Regional Hospital and clinical prof at the University of B.C., when the two brainstormed a more dedicated way to assist rural and remote doctors. They realized if it was tough for them to be alone with critically ill patients overnight in a busy city hospital, it must be “so much worse for our rural docs.”

Burke had just come off a six-hour call assisting a physician in Chetwynd with a COVID pneumonia patient in their 40s when the Times Colonist reached him. He said he invested $200,000 of personal savings to get the ROSe program started in 2017. He asked physician friends to support the group but didn’t pay them. Over time, the province and doctors tried different means of communication, but all came with challenges, from not having enough bandwidth to requiring too much battery power and a lack of encryption for privacy.

When “I was broke,” he said, Dr. Ray Markham, executive director of the Rural Co-ordination Centre and a clinical professor at the University of B.C., “single-handedly” provided emergency funding through the centre.

In 2019, the program received provincial funding through the centre, he said. Now there’s an app doctors can call up on a mobile device for immediate connection to a list of ICU doctors. If one is busy, the call automatically goes to the next one. “They call us an ‘intensivist in your pocket,’ ” said Burke, explaining many doctors put their smart phones in their chest pockets so both doctors have the same view of the patient.

The critical-care specialist group has since saved dozens of lives and assisted in hundreds of cases — ensuring many patients didn’t have to be flown out of their rural and remote communities.

“The doctor in the rural or remote community always has someone looking out for them,” said Burke. “The worst time is when you don’t get a call that somebody is struggling because they’re afraid to call.”

Former Canadian Medical Association president Dr. Granger Avery, who practised in rural and remote communities over four decades, said the ROSe program costs a “relatively small” amount of money — about $225,000 a year — but provides crucial support for physicians in high-stress situations in remote and rural areas, making it easier to recruit and retain them.

“How do we even account for the value of a life?”

Family physician Dr. Greg Costello works out of Bella Bella, between north Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii, where a handful of family doctors cover the hospital’s emergency department and long-term care — almost everything, in fact, but obstetrics.

“Some days I’m a psychiatrist, some days I’m a dermatologist, other days I’m an addictions specialist,” said Costello.

While he and his colleagues have a wide range of skills to treat their patient, when a plane can’t fly a critically ill person out, and other intensive-care specialists in the province are busy, Costello and his colleagues rely on the ROSe program.

“Having these people available at the drop of a hat to help us out is absolutely invaluable to me and my team and my patients.”

The hospital, the only one in the province based on a First Nations reserve, also serves smaller communities along the coast, such as Klemtu, accessible by plane or boat, or Ocean Falls.

Prior to the ROSe program, in the event of an accident or illness that required a life-saving intervention, Costello and other physicians would need to call their main hospital referral centre and request an ICU or internal medicine physician on shift, who may or may not be available for a phone consult, or may be rushed. The family doctor could try to arrange air transport for the patient, “but some days the plane doesn’t come in because it’s snowing, or it’s crazy wind, or it just can’t land.”

With ROSe and other real-time supports, Costello said, they can get help from someone “who’s not trying to run off and see another patient on their end.”

Costello said the ROSe doctor can see and hear what’s happening via video livestream and give advice in real time. Sometimes, it saves a life and sometimes, it allows a doctor who is alone in a small community to accept the inevitable.

Recently, Costello was doing everything to restart the heart of a young patient who had gone into cardiac arrest and the intensive-care specialist who was helping him remotely gave him “permission” to do what is often difficult for doctors to do — stop intervening.

“It takes the weight off your shoulders because a specialist sees that we’ve done everything that we can,” said Costello. “It made it easier because it wasn’t only my call, it was someone else as well.”

In another case, a pediatrician agreed with Costello that a child with an infection who appeared healthy was, in fact, seriously ill and was able to arrange a bed and transport for the patient while Costello continued with the hands-on care. The transport arrangements can require dozens of calls to hospitals and the specialist can advocate for the patient in ways the family doctor can’t.

“The child was out the door and down having surgery within four hours and I’m not sure that would have happened if I didn’t have the specialist … agree with me and help advocate,” said Costello.

In another case, last year, a patient turned up in the middle of the night with a severe head injury that involved brain swelling. The hospital didn’t have the required medication but an intensive-care specialist working with Costello via ROSe helped him find alternate medications to stabilize the patient, as well as arranging for a helicopter for both Costello and the patient.

“Sometimes you need more than one brain in these situations,” he said.

While new family doctors know they may be pushed outside their comfort levels in emergency situations in remote areas, he said, online-support systems help with recruitment, because the family doctor can have direct, uninterrupted and exclusive access to a specialist if needed.

“That help is available 24/7 within minutes and you’re not going to be judged or berated or talk to someone who’s irritated because they are busy with another patient or need to run an ICU,” said Costello.

Family physician Dr. Jolene Drake has just completed her residency training and is working out of Smithers, after finishing a locum in Hazelton. She typically works in one-doctor, one-nurse emergency departments where physical in-person support might be 45 minutes away.

Drake said working in Hazelton, she can call another family doctor for backup, “but it takes time” and that physician may not have the expertise needed for a significant trauma case. Telemedicine out of Terrace can be contacted by phone, but it doesn’t offer the real-time video interaction she has with ROSe.

“I’ve actually called ROSe for the last two emergency shifts I’ve been on,” said Drake. In one case, she was on the call for hours being walked through every step of a difficult surgical procedure.

Recently, the rural doctors were notified that the ROSe internet system would be down for updates for a couple of days and Drake said the physicians — new and experienced alike — were alarmed “because we are so dependent on them.”

One doctor asked for instructions prior to the service going down as he anticipated a difficult intubation that would have to be done. He followed the directions step by step.

“As a new doctor, working in emerg is hard,” said Drake. “I don’t know if I’d be comfortable working in emergency departments that are this small and this isolated without [outreach programs like ROSe].”