Death may be a universal experience, but it’s also a very intimate one.

Today, we share the story of how one family faced it. Manfred Pape was an adventurer through life — crossing glaciers, climbing mountains and descending into canyons. In his final weeks, at the end of a long battle with colorectal cancer, the Saltspring Island man, his family and Victoria Hospice allowed the Times Colonist to document his journey. Though there were moments of great sadness, the Pape family approached death with respect and love, calling it the most vivid part of life.

- - -

One by one, those who loved Manfred Pape dropped a memento into his grave.

His sister Maria gave a bus ticket, to show her older brother her new independence.

From son Andrew Pape-Salmon, it was Cheerios and coffee to represent the 7:30 a.m. breakfasts he shared with his father each morning in Manfred’s final weeks at Victoria Hospice.

Andrew’s wife added flowers from her garden. Her mother brought a spartan apple, the kind that grew abundantly on Manfred and Marion Pape’s Saltspring Island property.

In the intimate ceremony, they had carried Manfred’s body on a stretcher, said the Heart Sutra — a piece of Buddhist scripture that Marion chose to help his spirit along — and laid him to rest, carefully wrapped in a bamboo shroud, in the Royal Oak green burial site.

“It’s like we were on the edge of the cliff watching,” Andrew said one week later, while visiting his father’s final resting place at the edge of the woods, now imprinted with deer tracks.

“It was very eerie seeing the body down there. It was very final,” said Marion, who had buried her partner of more than 45 years. “We just tried to keep it as simple and natural as we could.”

Andrew Pape-Salmon listens to his father, Manfred, as he talks about his life at Victoria Hospice.

Photo: Adrian Lam, Times Colonist

For the Pape family, this day — May 29 — marked the end of a year-and-a-half journey that began Oct. 18, 2011. That was when Manfred — a pharmacist, train enthusiast, mountaineer, adventurer and towering specimen of health — was diagnosed with colon cancer. Two weeks later, they learned it had spread to his rectum, liver, kidneys and beyond — stage four cancer.

The odds were not good. Cancer is Canada’s biggest killer, with the mortality rate for colorectal cancer particularly high.

But this was a family that saw Henry David Thoreau’s words scrawled on a restaurant wall in Lake Louise and related to them: “I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.”

Manfred and Marion, a former librarian and community organizer with a radiant grin, had bonded over a love of travel and exploration as students in Toronto. Together with their only son, they crossed glaciers and descended into canyons, embracing opportunities to live in seven provinces and territories.

They treated this new journey as their latest challenge.

From the beginning, the Papes approached the illness with hope and good humour. Manfred nicknamed his tumour “Osama bin Laden” — it had bad cells, like al-Qaida — and vowed to conquer it.

Andrew, an environmental engineer, found a surgical team willing to take a chance on Manfred; for eight weeks after the surgery, they lived with the possibility that the cancer was gone.

Andrew and Marion started a blog, with Manfred’s blessing, inviting friends and family to share their journey.

“And the ride begins. Life will not be the same,” Marion wrote on the day they learned the cancer had spread. “When you are vulnerable, that is the time to touch the spirit. ... I have never felt more powerful and potent. Hopefully this crisis is not life-threatening, but if it is, we will pull together to do what is needed.”

There would be rollercoaster moments — surges of grief at each new piece of bad news, balanced by optimism when Manfred regained his appetite or appeared in good spirits or smiled.

Though they faced the same reality, each took a different spiritual journey. For Andrew, an agnostic, the rituals were physical and often connected with nature. It was important for him to be near his dad, to touch him. His greatest moments of reflection came during his bike rides from the Victoria Hospice.

For Marion, a former Unitarian lay chaplain and practising Zen Buddhist, there were meditations, sutras and strength drawn from the love, thoughts and prayers sent to the Papes from their community.

Manfred, a man of science, said he didn’t believe in God or the afterlife and felt at peace with that. But he also came to enjoy a nature-based blessing prepared by spiritual care volunteer Lynne Shields and, as one of his friends later told Marion, “Sometimes an illness is needed in order for the spirit to progress.”

As the prognosis became clear and Manfred’s body began to deteriorate, they each reached a point of acceptance: Death was coming.

Manfred was first.

“I think it happened before the doctors told him, before the second death sentence,” Andrew said. “He said, ‘This isn’t working.’ ”

Andrew counted three death sentences in the journey: The initial cancer diagnosis, the news that surgery hadn’t worked and the final move into Victoria Hospice, after hospice home-care workers identified Manfred — at a particularly difficult stage of dying at home — as a candidate for one of 17 beds at the Royal Jubilee Hospital palliative care facility. At the hospice, which depends heavily on donations and volunteers, the goal is to deliver comfort rather than a cure.

Manfred strayed a few times, as they all did; he once suggested that he’d like to do a hike that they knew would not be possible. But he didn’t play that game very often, Andrew said, and he appeared at peace with the reality that his life was ending.

Most surprising to Marion was that Manfred never complained.

Asked if Manfred had been a complainer through life, there was a pause before Andrew said, “Yeah, he was a complainer.”

They both laughed as they talked about his strong opinions. Manfred was both principled and outspoken, even as a quiet man.

Marion Pape drops water on husband Manfred’s lips.

Photo: Adrian Lam, Times Colonist

From Marion’s perspective, the change had to do with a realization on Manfred’s part: Though he’d loved solitary moments through life, he was now constantly surrounded by supporters — even making meaningful new friendships, as with one of his hospice roommates, Malcolm. It was the first time in his life that Manfred felt this level of unconditional love.

As a pharmacist with hospice training, Manfred might have understood death on a certain level, but there’s nothing like facing it directly.

“Until your hand touches it,” said Manfred in mid-May, “until you feel what the stone feels like, you don’t really know. I can describe a stone. It’s hard, it’s solid. Then there’s the shape to describe. But when you put it in your hand, you understand.”

He spoke from his bed in hospice, with a handmade quilt pulled up to his chin. His bony knees made a tent at the centre and he studied a cold Big Mac. He hadn’t been able to bring himself to eat it the night before; his taste buds just weren’t the same since chemo.

“Drink all your beer before you get cancer,” he said, making everyone in the room laugh, before taking a bite.

Marion described how, even when you think you’ve accepted death, it comes back to surprise you.

“We have had the privilege of time,” she said in early May, weeks before Manfred’s death. “But every time I have a new awareness, like today, it’s an incredible shock.”

Days before Manfred’s death, Andrew said he found himself going through the stages of grief, again, at condensed speed: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

But acceptance was a gift and they all recognized that.

“Once you’ve come to a point of acceptance, the caregiver role is almost heartwarming. It doesn’t have to be the bogeyman to look after your father. Once you come to a point of acceptance, it’s an act of love,” Andrew said.

Marion described caring for her husband as a role she learned along the way, not unlike motherhood.

“It is a profound privilege to accompany a person you love on his final journey,” she said.

At the same time, both spoke of hospice in glowing terms for the way it freed them from their roles as physical caregivers, as well as allowing Manfred to die with dignity. They could spend their final weeks with Manfred as wife, son and friend. For Manfred, it was “the bridge over troubled water,” according to a friend — making the decision to stop further treatment meant he was free to focus on what counted, including time with loved ones.

Marion called the moments before death the richest in life. As an end-of-October baby, she said she has always celebrated the autumn in its fullest majesty and significance.

“That’s what this period, just before you die, is. It comes out in all its greatest glory, it’s so magnificent … I think it’s a way that we realize every ounce of who we are,” she said.

Most people tend to go the way they lived. Licensed practical nurse Sandi Ogloff has watched dying soccer moms and organizers get suddenly chatty as their cognition lowers. They’re working through something difficult, just the way they have through life.

“People work through their journey right until the end,” Ogloff said.

Manfred was a man who seemed to grab life by the horns, so Ogloff said she wasn’t surprised to see that death came slowly to him.

“He’s a very strong person and he liked adventure and things like that,” Ogloff said. “So it wasn’t surprising to see that as he started to slow down, that he was still able to kind of control his surroundings and make choices.”

Ogloff was one of a team of nurses who got to know Manfred during his stay at hospice. They bonded over their shared history living in the North; she looked forward to his baths, because that’s when he told stories about his life.

“People near the end of their life like to talk about what they’ve done and you get a sense of what was really important to them,” she said.

One day, while bathing Manfred, Ogloff told him about a Helijet tour she had won in September. She was scared to death, she told him, and hadn’t booked it.

“He’s just like, ‘Oh no you have to do it!’ And he gets me all excited about it,” Ogloff said.

She said she booked it for August.

“I said, ‘OK Manfred. When I’m up there and I’m scared out of my mind, I’m going to be screaming your name.’ ”

Manfred gave his last smile when his sister Maria arrived from Ontario. He stopped eating about 10 days before he died and took his last sip of water three days later. There were periods in his final days when there were 50-second gaps between his breaths.

“The doctors kept saying it takes Manfred three times longer than everyone else to go through each stage, because he’s so robust,” Marion said.

On May 27, Andrew cycled to hospice for his daily coffee and breakfast ritual. That morning, he decided to take a conference call from Manfred’s room, instead of from work.

Manfred died during the call.

His family believes two things: That he held on for someone to be there and that, before he left, he wanted to see them carrying on with life.

On the one-week anniversary of Manfred’s death, Marion and Andrew met at the burial site.

“It’s strange to say, but I think I’ve been through a lot of the grieving process already, so it’s not as painful as I thought it would be,” Andrew said.

The routines of life have returned. And Marion is preparing for her first dinner party, her first home without Manfred in a long time: Andrew and his wife will be her guests.

A few weeks ago, Andrew told Manfred that he had taught him how to live and was now teaching him how to die. On this day, Andrew shares what he calls the most profound thing that Manfred told him, when he took a rare excursion out of hospice to check out Marion’s new condo.

It was a bittersweet visit. On one hand, Manfred was in good spirits. On the other, it was a home he would never live in.

“He said three things,” Andrew said. “One: I had a good life. Two: I lived it well. And three: I had no regrets.

“As a son, I think, ‘Were we able to continue that, to make sure it was still true until his final breath?’ ”

He believes they were.

Later in the year, they’ll plant a Western red cedar on the burial mound, to be nourished by Manfred’s body.

But on this day, Marion brings two pots of stinging nettles, setting them on his grave.

If she receives permission to plant them, she says, it will be her life-long source of the medicinal plant.

“People say, ‘Watch out for the stinging nettle,’ instead of recognizing how nourishing and healing it can be.”

Andrew Pape-Salmon and his mother, Marion Pape, place two stinging nettle plants

on Manfred Pape's green burial site at the Royal Oak Burial Park.

Photo: Adrian Lam, Times Colonist

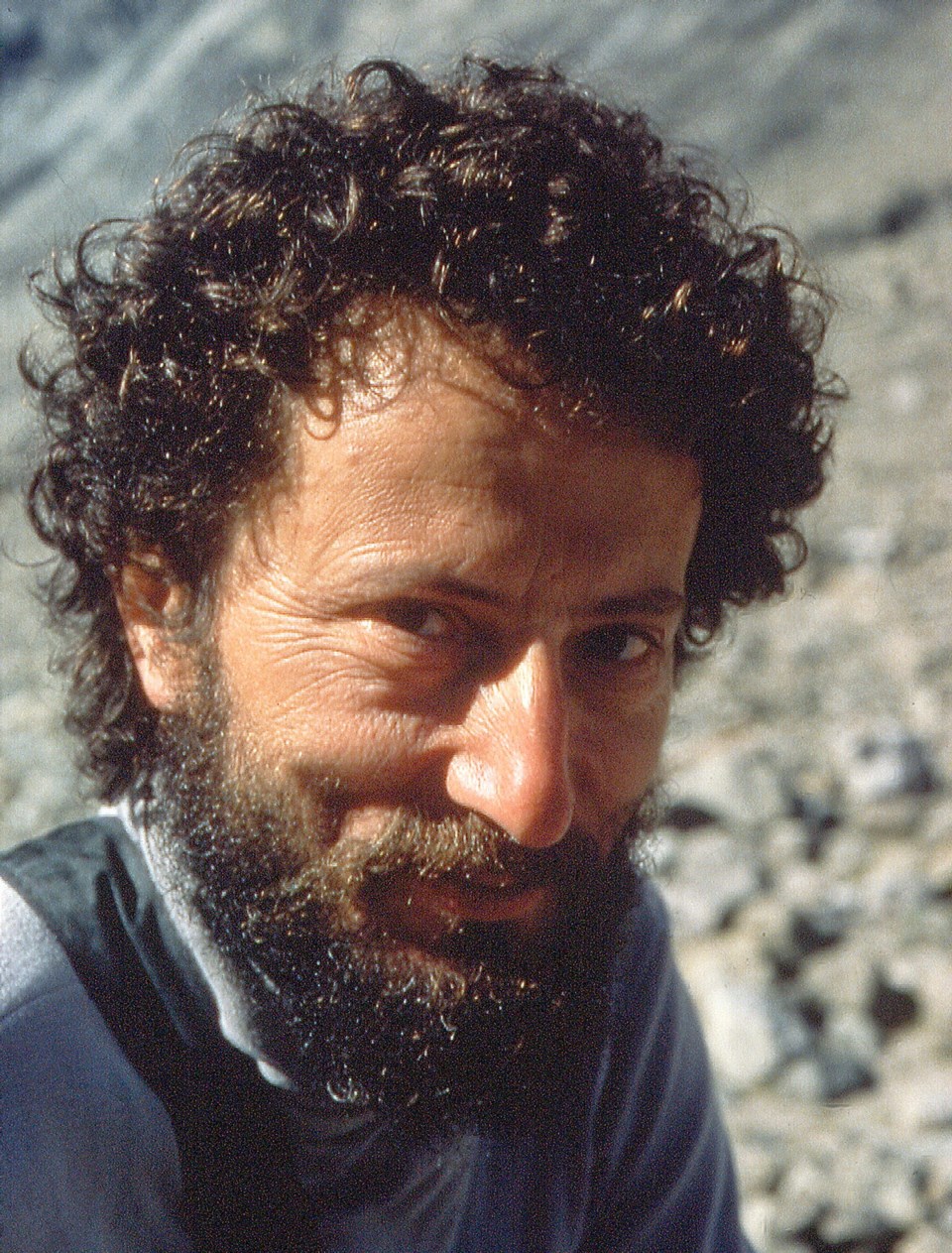

At age 45, Manfred Pape hikes in Auyuittuq National Park, Baffin Island, Nunavut.

Family photo