It was Sept. 1, 1918, and Tang Hualong, a former minister in the then newly created Chinese republic, was in Victoria at the end of a three-month North American tour.

He had a few hours before he was due to board a ship to Vancouver to begin his journey back to China, and had just gone to dinner at Doy Hing Low Restaurant, a banquet hall on Cormorant Street.

Tang was on a leisurely walk with about 40 other people toward a club on Fisgard Street about 8 p.m. when suddenly, Wong Chong, a local barber, emerged from the northern end of Fan Tan Alley carrying two .32-calibre revolvers.

Without a word, Wong shot at Tang twice. The second shot hit him in the head and killed him. Shortly after, Wong killed himself at the intersection of Pandora Avenue and Broad Street.

The murder motive remains somewhat of a mystery, but Wong was known to be a member of Sun Yat-Sen’s Chinese Nationalist League, better known today as the Kuomintang.

Sun had previously called for the death of Tang, who was on the opposite side of a civil war between rival governments based in Beijing and Canton. Sun accused Tang of making the trip to North America to raise money for the Beijing side.

Political tensions in Chinatown were at a peak at the time of Tang’s killing. “I cannot bear to sit here and watch my country perish,” Wong wrote in a letter left to a business partner shortly before his death.

Though no direct link between the Chinese Nationalist League and Wong’s actions was ever found, the Canadian government would briefly outlaw the organization, forcing its members to meet in secrecy at a Chinatown photography studio for about a year.

Wong would be remembered as a revolutionary martyr by the Chinese government and his grave in the Chinese province of Guangdong remains a popular tourist attraction.

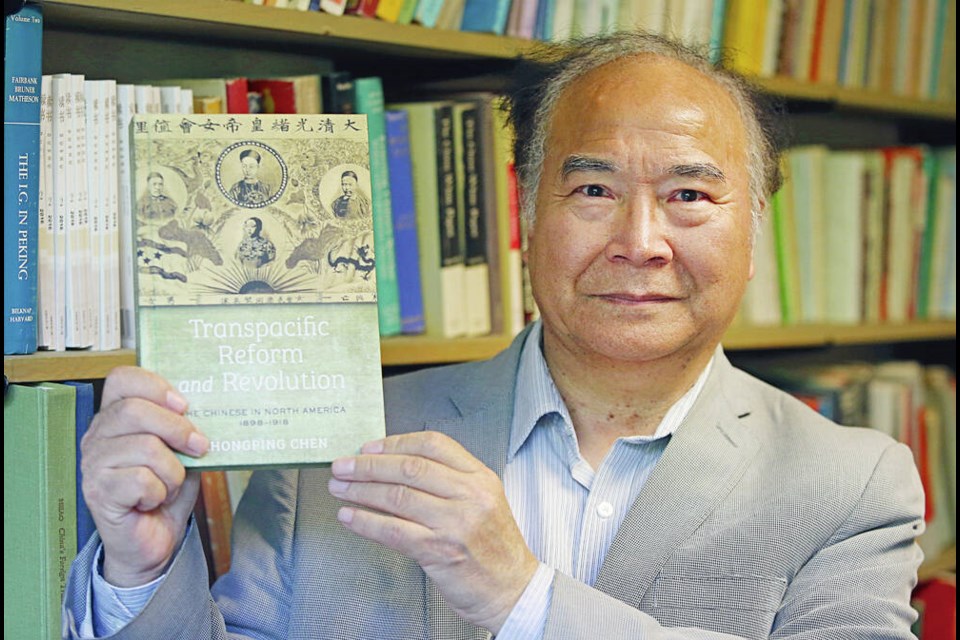

It’s just one of the stories told in Chen Zhongping’s latest book, Transpacific Reform and Revolution: The Chinese in North America 1898-1918, published by Stanford University Press, which is being launched today at the University of Victoria.

Chen, a history professor at UVic, details the rising political tensions in the two decades leading up to Tang’s assassination, including the planting of a pipe bomb on a windowsill of Victoria’s Chinese Methodist Church on Christmas Eve in 1899.

Then in 1915, Chinese Freemasons threatened to kidnap Chinese National League-aligned newspaper editors and to demolish their offices.

The following year, a brawl at the Chinese Public School on Fisgard Street involving members of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association and the Chinese National League eventually involved nearly 400 people.

According to Chen, it’s the first book — in English or Chinese — that attempts to combine modern Chinese history, Chinese-Canadian history, and Chinese-American history and Chinese diaspora studies. A good-sized section of Transpacific Reform and Revolution focuses on Victoria’s Chinatown from 1898-1918, a period when the seeds of the modern Chinese state were sown. “Usually, people do not pay much attention to Victoria,” Chen said in an interview. “They don’t know that it was politically important.”

Because citizenship was not an option for Victoria’s Chinese population at the time in the face of racial exclusion, Chen wrote, many of them remained connected and committed to their homeland. The connection worked both ways. Chen argues that the conversation in China at the time was influenced by ideas from the West.

The two competing visions for the future of the troubled Qing dynasty, then in the final years, was a move toward a constitutional monarchy or a revolutionary republic, championed respectively by Kang Youwei and Sun Yat-Sen.

Both visited Victoria and attempted to win support for their respective movements in the early years of the 20th century.

Sun’s election as the first provisional president of the Republic of China, then in a desperate financial crisis, was in part due to his perceived fundraising prowess stemming from past fundraising efforts in Victoria, Chen said.

Kang, on the other hand, helped found the first global political organization of overseas Chinese in Victoria. At the time, Chinese migrants mainly organized within their own clans and native-place associations.

The Chinese Empire Reform Association, founded in 1899, was meant to be a transnational corporation that would own banks, build steamships and construct railroads to help unify overseas Chinese to fight against the racist exclusion policies of the time, particularly in the United States.

At its peak in 1908, the Chinese Empire Reform Association would boast more than 200 branches on five continents, Chen said, adding that the association also had a groundbreaking women’s branch. “This was the first women’s political association in a thousand years of Chinese history,” he said.

Chen said he began researching the book in 2009 and finally managed to find the time to finish it during the pandemic.

Many of the stories he tells made their first appearance in the pages of the Colonist and the Times — predecessor papers of the Times Colonist. No complete copies of Canadian Chinese-language newspapers before 1914 have survived, making the two Victoria papers “very valuable” in his research, he said.

A book launch for Transpacific Reform and Revolution: The Chinese in North America, 1898−1918 is set for 3:30 p.m. on Tuesday in room A120 of the Cornett building at the University of Victoria.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]