Tony Hunt Sr., a hereditary chief of the north Island Kwagiulth people, world-renowned artist, champion and ambassador of traditional Aboriginal knowledge, died Friday at the hospital in Campbell River surrounded by loved ones. He was 75.

“He was such a big cultural person in our lives. This is a huge loss to our family,” said Hunt’s sister Leslie Dickie. “He lived the old knowledge. He was raised in the kind of ways you can only learn by reading about it now.”

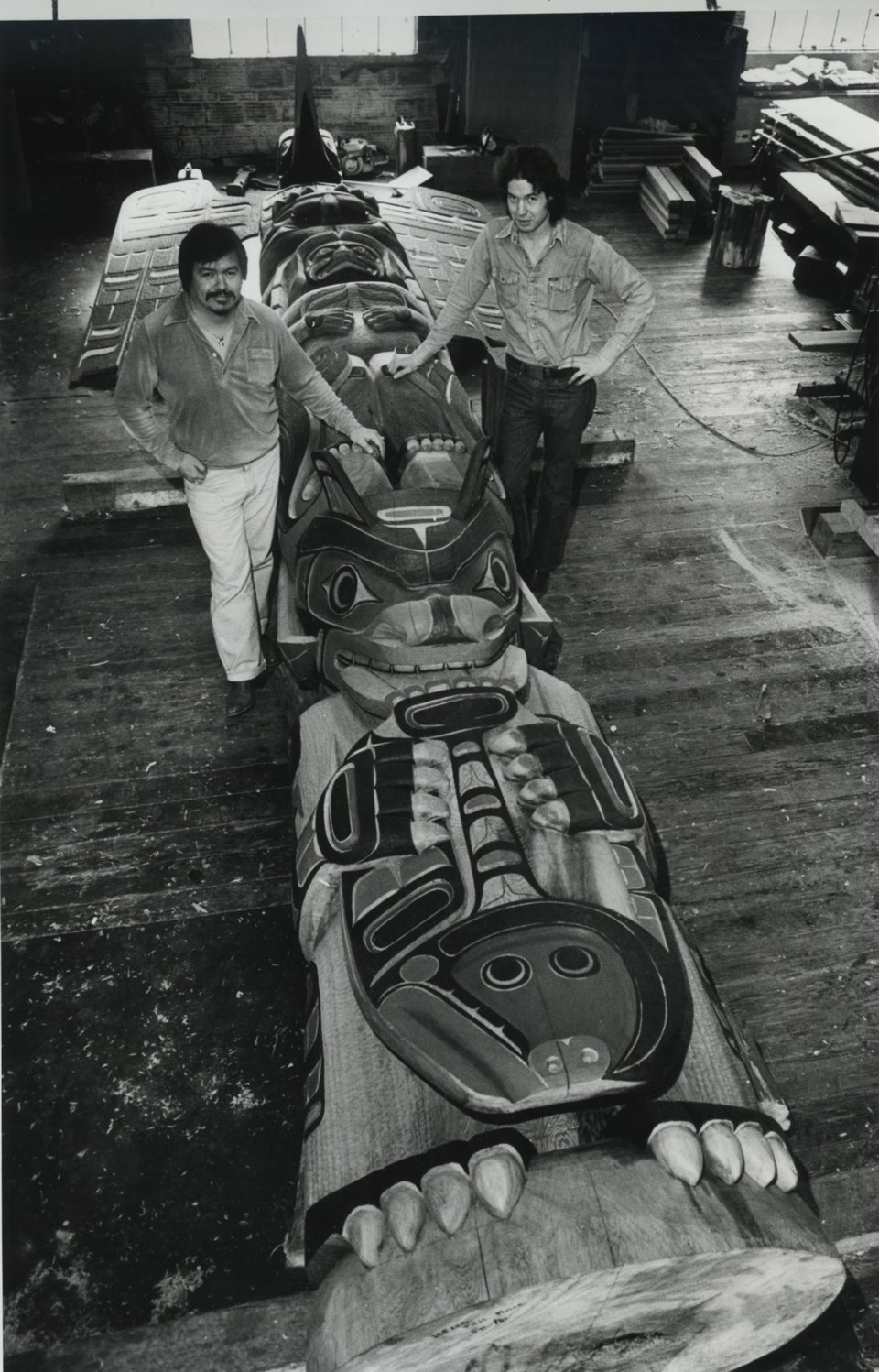

Hunt designed and created hundreds of totem poles with his family. His work includes Thunderbird Park and the big house at the Royal B.C. Museum, the totem pole in Victoria Conference Centre, and the ceremonial big house in Fort Rupert, the largest in the Pacific Northwest.

He was named to the Order of B.C. in 2010 and received an honorary doctorate from Royal Roads University.

Dickie said Hunt died from deteriorating health that worsened over the past few months, following the death of his son Tony Hunt Jr. The younger Hunt, 55, was also a celebrated artist who struggled with an ongoing illness.

“He never recovered from losing his son,” Dickie said. “He was overwhelmed with grief.”

The elder Hunt has two other children, Debbie and Steven, as well as four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Hunt was born in Alert Bay, the first of 14 children, and spent his early childhood in his home village of Fort Rupert on the northern tip of Vancouver Island.

He moved to Victoria when he was 10 years old with his parents Henry and Helen Hunt. His maternal grandfather, Mungo Martin, was the principal carver at the Royal B.C. Museum — charged with replicating and repairing works from along the coast as well as creating new ones.

Hunt’s father became Martin’s assistant and Hunt became his protégé, immersed in the technique and culture of traditional art.

“Mungo took Tony from an early age to train him in the traditional ways,” said John Livingston, who calls Hunt his teacher, mentor and longtime friend. The two met in the late 1960s when Livingston was a teenager and Hunt was in his early 20s, recently appointed assistant carver to his father at the museum after his grandfather’s death.

“They were ambassadors of Northwest culture to the world,” Livingston said, noting their works have been presented around the globe and to many visiting heads of state.

Livingston said Hunt was proud of everything passed down to him, including the Kwak’wala language, dances and traditions of the potlatch. When potlatches were outlawed by the federal government in 1885, Kwagiulth people kept the tradition alive in secret.

The first legal potlatch after the law was repealed in 1951 was by Martin in Victoria.

“Tony was extremely proud of his potlatch name, Nakapenkem, inherited from Mungo Martin. It means seven times a chief,” said Livingston, who ran the Arts of the Raven gallery with Hunt for 20 years.

He said Hunt was a longtime resident of James Bay and well known around the city among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike. He took traditional art seriously and was intent on sharing his knowledge by mentoring others at a number of carving studios around town.

“He said I want to see Native art out of the curio tourist shops and shown as a serious art form,” Livingston said.

“He will be missed as an artist and culturally for his knowledge but also really missed for advancing and as a teacher of Northwest coast culture.”

There will be a service for Hunt at the Fort Rupert great hall at 1 p.m. on Tuesday, Dec. 19.