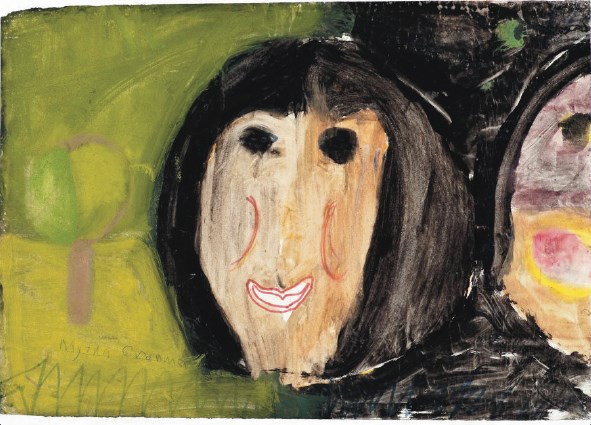

When Lewis George looks at the paintings he created as a child more than half a century ago, he sees artwork that changed the course of his life.

George, an Ahousaht First Nation hereditary chief, was sent to Alberni Indian Residential School when he was about six years old. Soon after his arrival, he jumped at the chance of taking art classes because they would get him out of early bedtime.

“They used to put us to bed at 6 p.m. and the art classes were between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m.,” he recalled.

It was during the evening that most sexual abuse happened — dorm supervisor Arthur Henry Plint was eventually branded a “sexual terrorist” by the courts. “I credit those classes with keeping me from being abused,” said George, who was physically abused at the school but escaped the sexual abuse that many of his friends and siblings suffered.

A repatriation ceremony and feast were held Saturday in Port Alberni to honour the return of paintings created between 1959 and 1966.

Some residential school survivors will take their paintings home. But the majority are lending them to the University of Victoria, where they hope the poster-paint artworks will tell the story of what happened when they were forcibly taken from their families.

“I want my story kept alive,” said George, who remembers the kindness shown to him by volunteer art teacher Robert Aller as being in stark contrast to the harsh realities of life at the school.

The 47 paintings were kept by Aller, who then bequeathed them to the University of Victoria, but their significance was not recognized until years later.

For the past two years, UVic visual anthropologist Andrea Walsh and a team of assistants have worked with aboriginal elders to find the artists.

The paintings are “incredibly important,” Walsh said.

“They mean so many things in different ways to the survivors, and reuniting people with these beautiful pieces they created as children is very unusual,” she said.

“We didn’t know this kind of archive existed until five years ago. All the archives were thought to be adult. No one considered that the children themselves might have made material pieces through which we can witness history.”

Walsh is now investigating whether similar records exist elsewhere.

Most of the Alberni paintings represent places or people known to the children, Walsh said.

“They tell us about the kind of relationships the kids had to places and people and culture. Residential school was about divesting kids of their heritage and traditional activities, so these [paintings] speak to the children’s knowledge of who they were.”

Wally Samuel, a survivor of Alberni residential school who helped co-ordinate the project, said everyone reacted differently when told about the paintings.

“Some got really quiet and others looked forward to seeing them,” he said. “But they all remembered being in art class.”

Paintings not taken by their owners will be displayed at UVic’s Legacy Art Gallery, at 630 Yates St., starting May 8.