When the doors open at the St. John the Divine food bank, the crowd snaking around the block slowly moves down the stairs and into the crypt.

Volunteers quickly lay out donated produce and bread, known as “bounty,” and it’s first-come, first-serve.

The food bank operates twice a week but clients can only visit once a month. It’s one of the few in town where they get to choose the non-perishable items they take home, instead of a standard prepared hamper.

On the first Tuesday of the month, the room is full of a noticeably older bunch compared with those who visit later in the month. They come prepared, with reusable shopping bags, friends who help interpret for those who don’t speak English, and shopping lists.

It is just one scene that shows how thousands of Victorians are struggling to live below the poverty line, an increasing number of them approaching or well past the retirement years.

Read the Hidden Poverty series

- Introduction: The growing problem of hidden poverty in Greater Victoria

- Part 1: How domestic violence is driving homelessness in Greater Victoria

- Part 2: Childhood poverty and the single-parent trap

- Part 3: The growing concern of the city’s underemployed and underpaid

- Part 4: An aging population in financial limbo and a housing crisis

- Part 5: Small changes coming and big changes needed to address local poverty

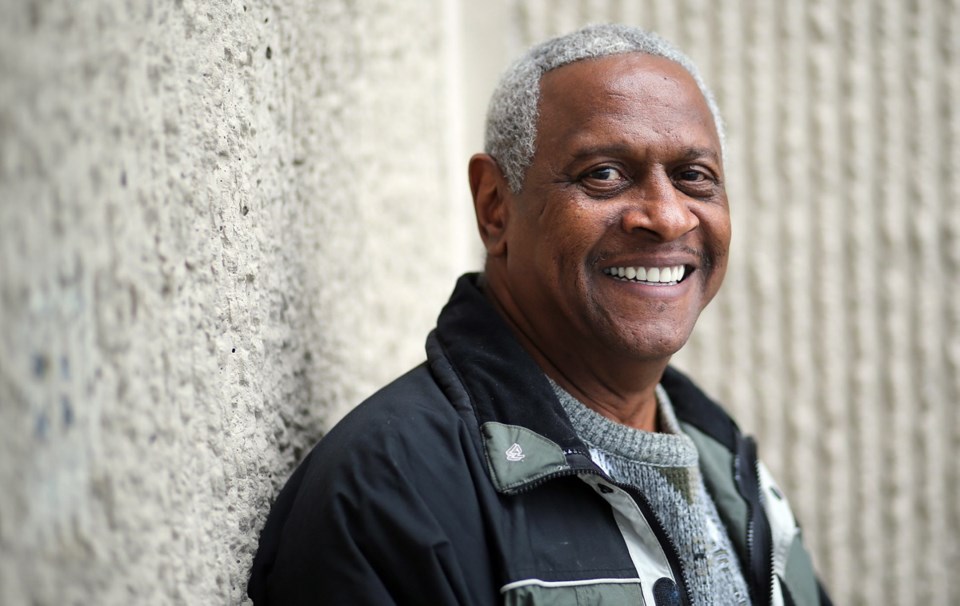

“I should probably go for the protein items,” Thomas Lee Lewis says as he looks over the list and chooses canned meat and beans.

Lewis, 63, lives on $800 a month from social assistance. With $360 going on rent at a subsidized housing co-operative, there’s not much left for food and necessities. So he scours flyers for deals and has made friends with managers at his favourite shops who let him know when a deal comes up. He hits food banks a few times a month, but tries to leave the free community meals “for those who really need it,” he said.

Lewis, from Memphis, Tennessee, grew up in a housing project riddled with violence. A few years after he moved to Victoria, his marriage fell apart and a compensation dispute over a work injury left him broke and depressed. He turned to drugs and became homeless. Then, during surgery six years ago, he had an out-of-body experience, he said.

“I was looking down at myself and heard a voice say, ‘You have to change,’ ” Lewis said. “I didn’t think I could do it, but [he] said I’ll be with you.”

Lewis said he decided to get his life together and become more spiritual. He’s now a minister, blogs about spirituality and volunteers.

‘‘When I first moved into my place, I had nothing. I slept on the floor. But I was so grateful,” Lewis said. “I had to learn to manage my money.”

Lewis made a list of all the furniture and other things he needed and forced himself to save $100 a month until he could afford each one. It’s a discipline he hopes will take him through his old age, as he didn’t save for retirement.

According to a Statistics Canada report released this month, 28.5 per cent of seniors living alone are categorized as low-income. With more than 12 million Canadians who do not have workplace pension plans coupled with low contributions to registered retirement savings plans, that number is set to rise.

* * *

‘We’ve seen a major increase of older people on [the Canada Pension Plan] looking for work,” said Jo Zlotnik, a case manager at WorkLink Employment Society, which serves an area stretching from Langford to Port Renfrew. People coming in include the over-70s . “I had one man tell me he’s starving on CPP,” Zlotnik said.

Some seniors find work at companies such as Wal-Mart but it’s tough for someone who doesn’t have the technical skills of the younger generation, Zlotnik said.

Michelle Mungall, NDP MLA and opposition critic for social development, said policies that force seniors off assistance and onto reduced CPP benefits also contribute to dangerous levels of poverty.

“Then they’re at a reduced income for the rest of their life. That’s not lifting anyone out of poverty,” said Mungall, who proposed a poverty reduction and economic inclusion act in the legislature in October. It was rejected.

“We are definitely seeing a trend over the past few years of older people using our shelters,” said Kathy Stinson, executive director of Cool Aid Society, a non-profit organization that focuses on the development of safe, affordable housing.

In 2013-14, there were 208 unique shelter users over 55, up from 157 in 2010-11. Over-55s make up about 15 per cent of all shelter users.

In October, 82-year-old Ginette Hodgson showed up at the Rock Bay Landing shelter with nowhere to go. Case workers helped her with her finances but a broken hip landed her in hospital, where she’ll stay until she can get suitable housing. Others in their 60s, 70s and 80s staying at the shelter can wait months or even years for housing.

* * *

Organizations such as Our Place Society, which offers free meals and services to the poor and homeless, are also seeing a consistent increase this year in the number of seniors, many of them new faces.

“The trend is the population in general is aging, which includes people in the poorest sectors. But there are significant affordability issues [in Victoria] as well,” Stinson said.

With the Victoria rental vacancy rate dropping to 1.5 per cent in October from 2.8 per cent in the same month last year and the average cost of a bachelor apartment more than $700 a month, elderly singles on a basic pension have few options.

“We have a few projects on the go to address that,” Stinson said, noting that in the past decade three housing complexes have been set up in Langford, Victoria and Saanich to house 113 seniors. “We also have seniors in our other buildings.”

A $6.6-million, 45-unit Cool Aid Society seniors housing project has most of its core funding and permits approved, and is set to break ground in Saanich next year.