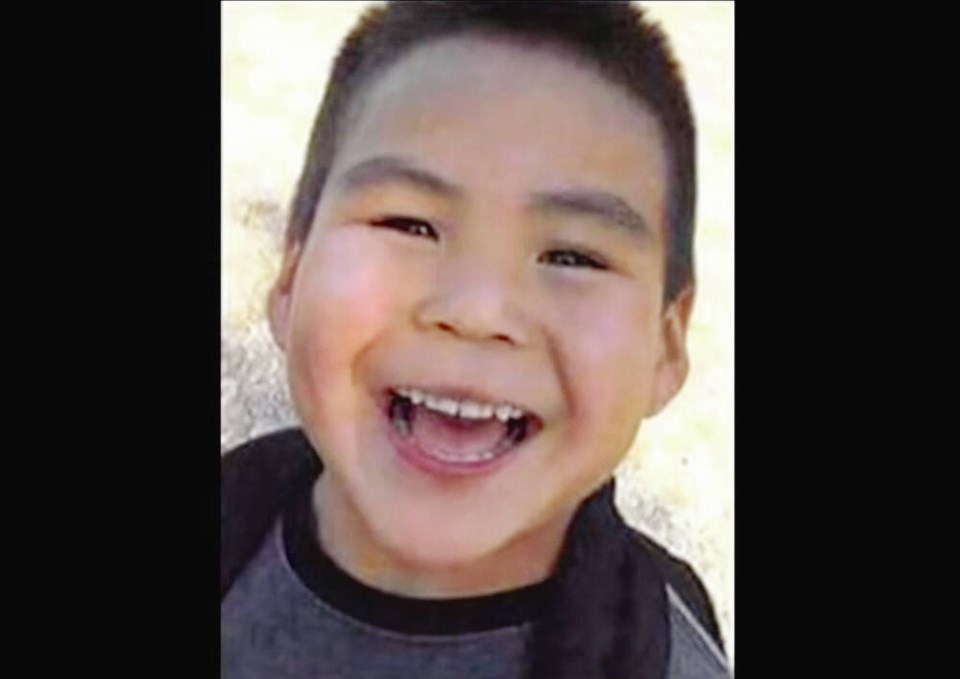

B.C.’s representative for children and youth should have conducted a full investigation into the 2018 death of a six-year-old Indigenous boy in Port Alberni, says the official who reviewed the file.

Jody Bauche worked as an investigative analyst for Representative Jennifer Charlesworth from February 2018 until August 2021 and was responsible for the comprehensive review of Dontay Patrick Lucas’s death.

“It was a horrific file to investigate and even more devastating that the [representative] was silent about it,” said Bauche.

Dontay died on March 13, 2018, of blunt-force trauma to the brain after being transitioned back into the care of his mother by USMA Nuu-chah-nulth family and child services.

His mother, Rykel Charleson, and stepfather, Mitchell Frank, deprived the boy of water, food and sleep, hit him, bit him and forced him to hang by his knees from the top of a door until he fell.

The couple, who were originally charged with first-degree murder, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and are to be sentenced in Port Alberni in May.

In an emailed statement, Charlesworth said legislation prevents her office from launching a formal investigation until criminal proceedings have been completed.

However, after the comprehensive review was completed, Charlesworth made the decision to “not conduct a full investigation into the child’s life and death due to a number of factors, including the potential further harm and trauma it could cause the family and community, and the amount of time that has passed since his death and how that might affect the quality of the investigation.”

The Ministry of Children and Family Development received a summary of the findings of the comprehensive review in the summer of 2021, “with the understanding that the information would contribute to the ministry’s process of ongoing quality assurance and help inform improvements to practice,” said Charlesworth.

Bauche maintains that Charlesworth’s mandate includes investigating Dontay’s death. Her review looked at all the child welfare and related family records. She also looked at representative for children and youth records, and discovered the representative had opened a file on Dontay in 2016 — two years before his death.

Bauche said it was a “really tragic case to review,” noting Dontay went into foster care shortly after he was born and had been in five different foster homes before he was five. “The one consistency in his life was the daycare he attended,” she said.

In 2016, when USMA Nuu-chah-nulth family and child services began planning to return Dontay to his family, the Hummingbird daycare called the representative for children and youth with concerns about how quickly the process was going, Bauche said.

But USMA ended up returning him to his mother despite the daycare’s concerns.

It was also tragic to look back and see how many injuries Dontay had come to school with, she said. The school sent reports to USMA that Dontay had bruises on the side of his face, his arms and his back.

One of the big questions in Dontay’s file was why USMA didn’t respond to concerns that he was being neglected and abused, she said.

Bauche said she pushed the representative to have a meeting with the community and with USMA to share her findings from the comprehensive review to support some sort of healing process.

“We had this information and we brought it forward and nothing happened,” said Bauche, who is Métis.

“I wanted the representative to do far more on this file. Why does the office exist if you’re not going to change anything?”

Bauche is concerned that the Port Alberni area is still dealing with intergenerational trauma from the Alberni Indian Residential School, which operated in the community from 1900 to 1973.

“I brought that to light because we were seeing a different kind of violence occurring for children in that area and I really believe it’s because of the lack of ability of the government to provide the proper resources for healing,” said Bauche.

“The government hasn’t caught up to the damage the residential schools caused, but it was very apparent to me that this was symptomatic of that community. This wasn’t the first situation where a child died at the hands of a family member in that community.”

Having Dontay hang by his knees from the top of the door, denying him food and water — all of that happened in residential schools, said Bauche.

“Children were tortured like that all the time. That’s why it’s worse now. Communities are doing it to themselves.”

Bauche said she still tries to wrap her head around Dontay’s death.

“Why wasn’t he removed? Weren’t there enough foster placements? Why wasn’t there some family to take him?” she asked.

Several of Dontay’s foster mothers have spoken out, calling for more accountability from the Ministry of Children and Family Development and Indigenous child services. They say they are upset and disillusioned that the needs of children appear secondary to the push to return them to their Indigenous communities.

Foster mother Amanda Watts told the Times Colonist she was twice asked to take Dontay back after he was abruptly removed from her care.