As B.C. ushered in Canada’s first permanent safer drug supply program, the parents of an Oak Bay teenager who died of a drug overdose said if prescription opioids were available for their son, he would be alive today.

Mental Health and Addictions Minister Sheila Malcolmson announced a new policy Thursday to expand access through existing clinics to safer prescription drugs, including oral opioids, for people at risk of overdosing on toxic street drugs tainted with fentanyl, carfentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

People who have been clinically assessed will have access to opioid alternatives, including fentanyl patches already being used in trial projects, as well as fentanyl (Fentora) tablets and expanded use of hydromorphone.

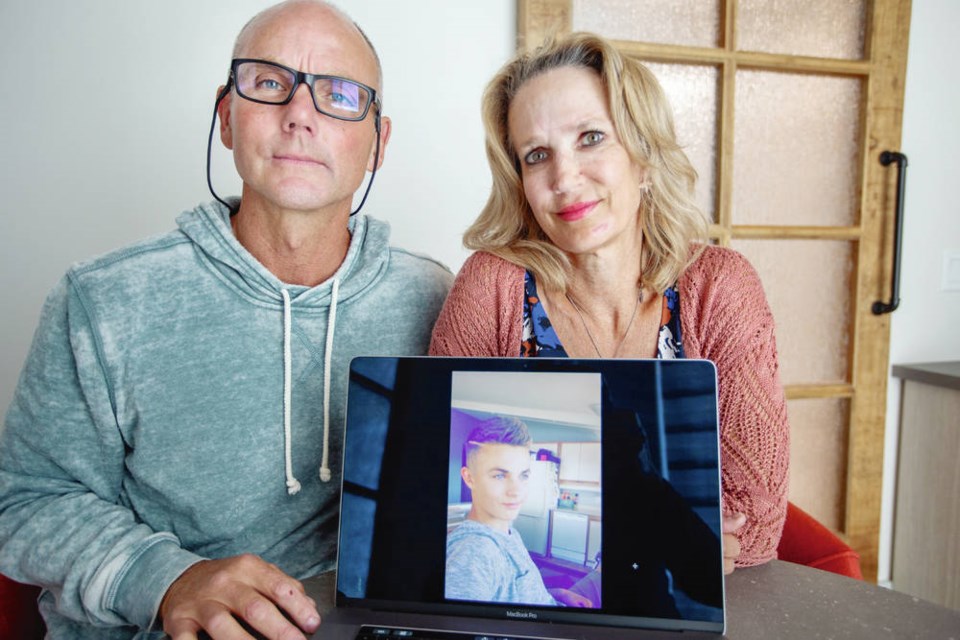

Rachel Staples, whose 16-year-old son, Elliot Eurchuk, died in 2016 after taking illegal fentanyl-laced drugs ordered over the internet, said the province should have taken this step “long ago,” when it declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency. Since then, about 7,000 fatal overdoses have been recorded, hitting record highs during the pandemic. Eurchuk, who would have turned 20 on July 11, became addicted after he was overprescribed prescription opioids following surgery for a sports injury, his parents say. He ordered what he thought was a safe supply on the internet. Instead, it was laden with several drugs, including fentanyl, said Staples.

Malcolmson said the province is the first to offer safe supply, and has had to move carefully as it responds to the urgent need.

Funding of $22.6 million will be allocated over three years to five health authorities to expand and establish new programs in phases.

The program will be available through clinics that currently prescribe safer drugs. More facilities are expected to be added, but the number has yet to be established. Health authorities are expected to provide implementation plans by the end of the month.

The federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act requires prescriptions for the alternative safer supply being offered in B.C. The province has lobbied Ottawa to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use to reduce the stigma of substance use.

“Once fully implemented, more people who use illicit drugs can be prescribed a broader range of safer alternatives, covered by PharmaCare, including a range of opioids and stimulants as determined by each program and prescriber,” Malcolmson said.

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said safer supply is just one solution. “There is no one single measure that is going to get us out of the toxic drug crisis, but this is one more step in the right direction.”

About 6,000 people in the province have accessed some form of drug alternative in the past year, said Henry, noting 60,000 are estimated to have a substance use disorder.

Development of the new policy included consultation with the B.C. College of Physicians and Surgeons. Henry said protocols established at clinics through health authorities will allow the college to know who is prescribing the alternative medications.

AIDS Vancouver Island has been running the Victoria SAFER Initiative, funded through the federal Substance Use and Addictions Program of Health Canada, for almost a year, giving about 100 people access to pharmaceutical alternatives through physician prescriptions.

The program’s capacity in Victoria is limited, said project director Heather Hobbs, partly because it doesn’t allow for prescribers outside specific safe-supply programs. That makes it especially challenging in communities where such programs don’t exist, she said.

Hobbs said a more flexible distribution model that includes, for example, compassion clubs would reach more people.

The current limited access puts an “incredible amount of pressure” on programs like hers, which are already facing capacity challenges, said Hobbs, adding decriminalization and legalization of drugs are also needed.

Some physicians in Victoria — including a group based at Cool Aid — are prescribing alternatives to toxic illicit drugs under B.C. guidance issued last year as part of a temporary safe supply program in the early days of the pandemic, due to the greater risk of overdose by people using drugs while isolating.

Expanding access to safer drugs helps people understand they can get off drugs if they want to get help, said Staples. “It’s also a way to de-stigmatize addiction and substance use disorders and get the [people who use drugs] into the presence of clinicians who can at least make an attempt to educate them and get them going in the right direction.”

The safer supply program will be monitored by the B.C. Centre for Disease Control and evaluated by a consortium of researchers, with adjustments made as needed, the province said.

- - -

To comment on this article, send a letter to the editor: [email protected]