An earthquake early-warning system that will send alerts to cellphones and emergency broadcast systems is expected to be in place on Vancouver Island and in the rest of the province by early next year.

In the event of a mega-thrust earthquake — the kind that results in major shaking and damage — Natural Resources Canada said the system could give coastal communities several minutes of warning.

Those extra minutes could save lives by getting people into safe positions, while triggering automated systems such as diverting planes from landing and stopping traffic on bridges, said federal seismologist Alison Bird of the Geological Survey of Canada’s subdivision in Sidney.

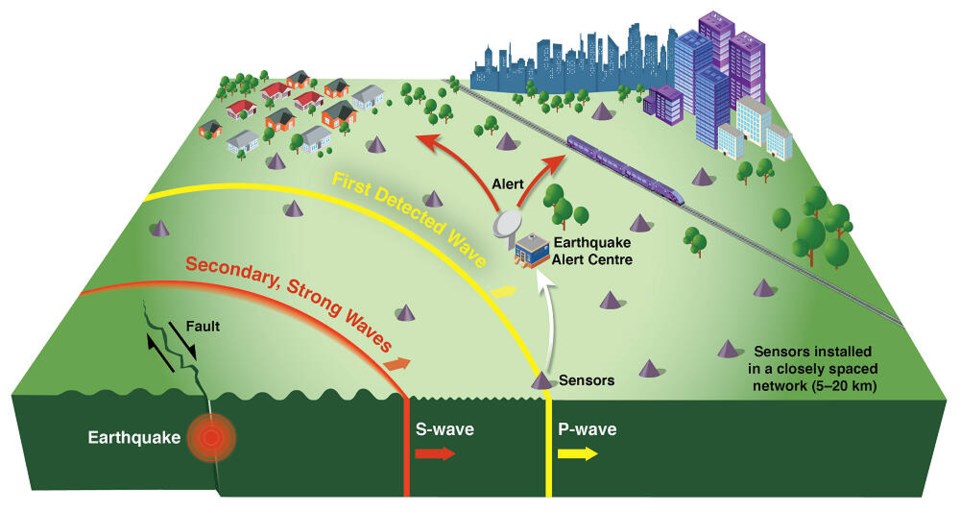

The early-warning system is designed to detect earthquakes through a network of sensors — some planted in the ground and others installed in buildings — that will estimate the shaking hazards and alert communities at risk.

Bird said several dozen sensors are being installed around the Island and in the capital region. About 100 sensors will cover the B.C. coast and Lower Mainland, with the system expected to go live in early 2024.

Earthquakes release energy that travels through the ground as seismic waves. The sensors detect the first energy to radiate from an earthquake, called the P-wave, which rarely causes damage.

The sensors transmit the information to data centres, where a computer calculates the earthquake’s location and magnitude, and the expected ground shaking across the region.

The method provides a warning before the arrival of secondary waves, called S waves, which bring the strong shaking that can cause major damage and potential loss of life.

The systems have already proven effective in Japan, Mexico and the U.S., said Bird.

Last March, when Tohuku, Japan saw a 7.4-magnitude earthquake, a bullet train travelling 300 km/h was immediately stopped because of a similar sensor system on the rail line, averting a major derailment and loss of life, Bird said.

Early earthquake warning alerts will be sent to the public through national alerting systems similar to an Amber Alert, said Bird.

Bird suggests going to Shakeout B.C. and other websites to find out exactly what to do if you receive an alert. “Get under your desk or table. If you’re in bed, stay there and put a pillow over your head. If you’re in a wheelchair, lock your wheels.”

Government operations centres and critical infrastructure operators could use the alerts to set off automated responses, such as turning off gas valves, automatically opening fire hall and ambulance doors, stopping trains and closing entrances to bridges and tunnels. Hospitals could halt surgeries and elevators could be moved to the nearest floor with doors open.

The system will also issue alerts for potentially harmful earthquakes from Washington state.

Natural Resources Canada will use the same software developed by the U.S. Geographical Survey along the Pacific Coast and has entered into a partnership agreement.

Bird said earthquakes generating low levels of shaking will not produce alerts. And sites very close to an earthquake’s epicentre may be in the event’s “late alert zone,” where alerting is not possible.

She said alerts are based on the level of shaking and not necessarily the strength of the quake.

The entire early earthquake warning system, which is costing $36 million to roll out, will also include the Ottawa River Valley and the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

A similar alert system is already in place and being tested on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

University of Victoria-based Ocean Networks Canada has deep-sea early earthquake warning sensors connected to its NEPTUNE cabled ocean-floor observatory. With land-based sensors, it forms an integrated network located close to the Cascadia Subduction Zone mega-thrust fault, and can provide quick notification of the arrival of ground shaking from an earthquake.

When a 4.8-magnitude earthquake struck 34 kilometres off Tofino on Nov. 25, the Ocean Networks Canada sensors were able to provide 43 seconds of notification to Vancouver and Victoria. Victoria was 235 kilometres from the epicentre and Vancouver 231 kilometres.

The 43-second notification was independently verified by a sensor located along the SkyTrain Canada Line in Richmond, which is participating in testing of the sensors.

The earthquake was considered small and did not cause any damage, but proved the system can give valuable time before a potential shaking event.

Ocean Networks Canada has been testing its network for several years, and is currently working with partners to launch an earthquake notification system so operators of critical infrastructure can activate safety and emergency response measures and notify those in harm’s way.

Ocean Networks Canada said the P-waves from the Tofino earthquake were detected on 25 sensors — five in the ocean and 20 on land. As a result of the earthquake, the sensors continued to report shaking at their location for about two minutes.

Mega-thrust earthquakes happen in subduction zones where one tectonic plate is thrust under another, which is the case on the West Coast on the Cascadia subduction zone.

From mid-Vancouver Island to northern California, the Juan de Fuca Plate is slipping beneath the North American Plate. The plates get stuck, but eventually the build-up of strain releases and earthquakes of all strengths can occur.

Last year, the province recorded about 2,500 earthquakes, most off the west coast of the Island and Haida Gwaii, many of which were not felt. The largest five were between magnitude 5 and 5.5, levels that rarely cause damage.

Natural Resources Canada has identified 13 mega-thrust earthquakes over magnitude 9 in the Cascadia subduction zone over the past 6,000 years, an average of one every 500 to 600 years. Some have been as close together as 200 years and some as far apart as 800 years.

One of the last major mega-thrust events was more than 300 years ago.

On Jan. 26, 1700, the west coast of North America experienced a massive mega-thrust quake and tsunami. A magnitude 9 earthquake caused strong shaking that would have lasted for minutes, triggering a tsunami that hit coastlines all around the Pacific Ocean, devastating coastal villages from Vancouver Island to northern California and even causing damage on the coast of Japan.

Natural Resources Canada said the earthquake’s shaking collapsed houses of the Cowichan people on the Island and caused numerous landslides. The shaking was so violent that people could not stand and so prolonged that it made them sick.

On the west coast of the Island, the tsunami destroyed the winter village of the Pachena Bay people, leaving no survivors. The events are recorded in the oral traditions of the First Nations people.

Natural Resources Canada says a similar offshore event will happen again, representing a “considerable hazard” to those who live in southwest B.C.

Inland quakes are a greater threat to major West Coast cities than offshore ones, however, because they can be much closer to urban areas and occur more frequently, it said. An inland magnitude-6.9 earthquake in 1995 beneath Kobe, Japan caused 5,500 deaths and more than $200 billion in damage.

There have been four magnitude-7 or greater earthquakes in the past 130 years in southwest B.C. and northern Washington state.