At 3:30 p.m. on Jan. 23, 1906, the lighthouse keeper at Cape Beale on Vancouver Island sent an ominous message by telegraph.

“To Captain Gaudin, Victoria,” it read. “Steamer Valencia in bad place. One hundred on board. Rush assistance. Six men just reached here. Say between 50 and 60 are drowned.”

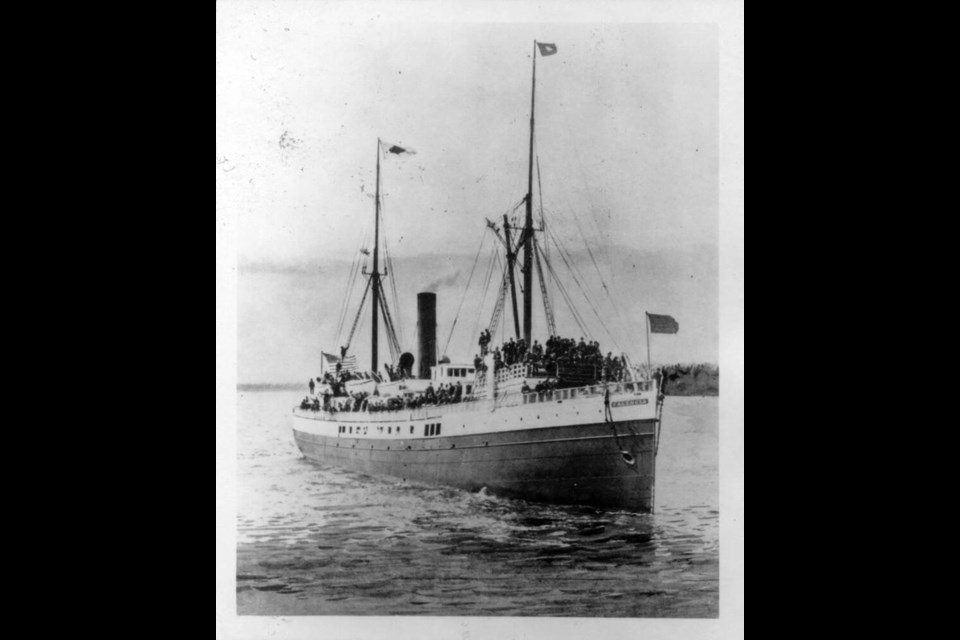

The SS Valencia was indeed in a bad place, stranded on top of a reef it had hit just before midnight on Jan. 22.

“They hit a reef and started taking on water,” said Heather Feeney, collections and exhibits manager of the Maritime Museum of British Columbia in Victoria. “The captain thought that the best course of action was to push forward higher onto the reef, to ground them so that the ship wouldn’t just sink, it would buy them some time.

“It did buy them some time, but didn’t actually help all that much. The ship eventually got broken up by the waves, and every woman and child on board died.”

It was chaos. As water flooded in, it cut the electricity, so the stranded ship was in total darkness. The Valencia had also run onto Walla Walla reef in the middle of a savage gale.

“For the following day and a half, the grounded Valencia was relentlessly attacked by vicious winds and unrelenting waves,” says an article on a Parks Canada website. “Attempts to launch lifeboats from the ship proved futile. The few who made it to shore were almost all killed, their bodies dashed against the rocky shore. In the end, only 37 passengers survived the disaster.”

Two lifeboats did reach the shore, which was apparently only 100 yards away. But the shoreline was largely sheer rock cliffs, so it was difficult to land on. When they did land, the men on them marched off in different directions, hoping to reach a lighthouse.

After they reached Cape Beale, word of the disaster got out and ships arrived to try to attempt a rescue. But the weather was so rough they couldn’t get near the Valencia for fear of going aground as well.

One rescue party went inland and reached a bluff near the wreck, which brought cheers from the passengers still on board the ship. But the would-be rescuers watched in horror as a “tremendous climacteric swell” smashed into the Valencia.

“They saw the battered hulk yield with a long tearing crackling noise, then divide and sink into the maelstrom of seething water,” said a story in the Jan. 27 Vancouver World.

“They saw the people, who only a few minutes earlier had voiced their rejoicings at apparent deliverance in cheer after cheer … go tumbling, sliding, whirling into the sea.”

A public commission on the Valencia found that 126 people had died in the tragedy. But the Parks Canada website says 136 people died, which makes it one of the deadliest disasters at sea in British Columbia, after the SS Princess Sophia in 1918 (where 367 people died) and the SS Pacific in 1870 (which caused an estimated 250 deaths).

The commission found that the Valencia’s Capt. Johnson had miscalculated where the ship was by six per cent. It had left San Francisco on Jan. 20 bound for Victoria and Seattle, but had overshot the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and wound up hitting a reef farther up off the coast, near Bamfield.

Newspaper coverage of the event was extensive, with several extra editions. The initial reports said there were 100 people aboard and 50 to 60 had been killed, but this was revised daily.

The most dramatic illustration of the wreck ran in the Jan. 28 Victoria Daily Times. It showed the Valencia aground on the reef, surrounded by turbulent seas, waves smashing into the steep shoreline.

In response to the shipwrecks off the west coast of Vancouver Island, the federal government created the West Coast Trail in 1907 to aid in the rescue of survivors of shipwrecks.

The Maritime Museum of British Columbia in Victoria will have an exhibit on the origins of the West Coast Trail and the SS Valencia that starts April 11.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]