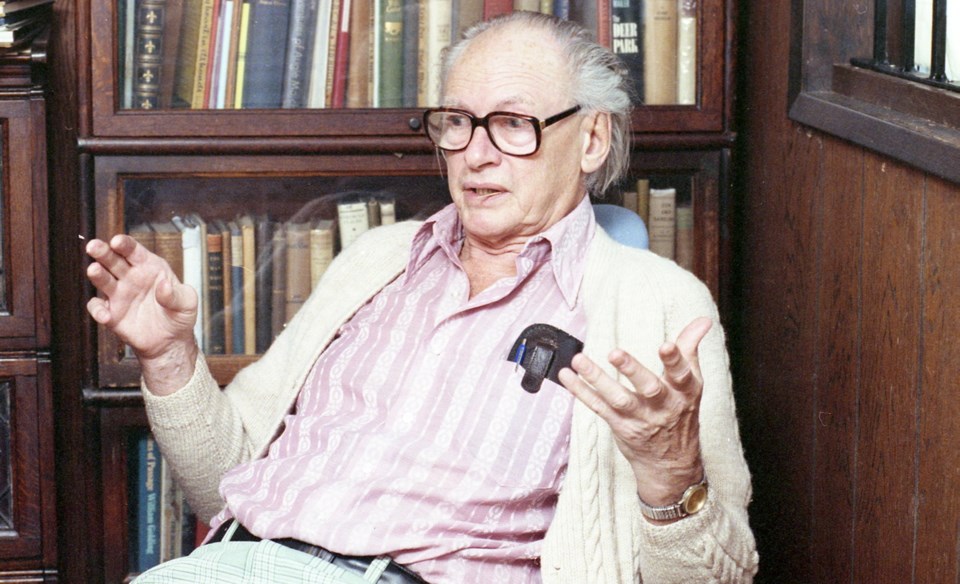

Victoria right-to-die advocate John Hofsess says he killed eight people who wanted to die, including Sidney poet Al Purdy.

Hofsess, founder of the Right to Die Society of Canada, took his own life “as planned” in Switzerland on Monday. In an article in Toronto Life published the day after he died, Hofsess describes how he and retired office worker Evelyn Martens took part in the suicides of eight people between 1999 and 2001. Hofsess and Martens created an underground assisted-death service for society members, wrote Hofsess.

Purdy was one of them. The poet joined the society in 1997 and asked Hofsess for a private visit in 1999. At age 81, Purdy was ill with metastasized lung cancer, severe arthritis, peripheral neuropathy and atrial fibrillation. Hofsess met Purdy at his winter home in Sidney.

“Al told me he wanted to die, the sooner the better,” wrote Hofsess.

But his wife, Eurithe, did not fully share her husband’s views.

In early 2000, Purdy told Hofsess he was fed up with suffering. He made the decision to end his life and his wife seemed willing to comply, Hofsess wrote.

By this time, Hofsess had spent years researching how to end a person’s life quickly and painlessly. His method involved drinking a glass of wine with Rohypnol, a sedative 10 times stronger than Valium, then placing an “exit bag” over a person’s head, pulling a drawstring and inflating the bag with helium.

“All he had to do was sip his wine and say farewell to the love of his life, while his favourite music played quietly in the background. I felt honoured that he delegated the technical details to me.”

On April 20, 2000, with his wife by his side, Purdy drank a glass of Chilean wine laced with Rohypnol and passed out. Martens placed the exit bag around Purdy’s forehead and Hofsess filled it with helium.

“Evelyn pulled the bag down over his head and sealed the collar. I increased the helium flow.”

At the time, the Times Colonist and other media reported that Purdy died after an 18-month battle with lung cancer. Hofsess said he concealed the manner of Purdy’s death so he could continue helping people to die.

“I viewed my actions not as defying Canadian law but rather as placing ourselves into the future — setting an example of how it was possible to die in a voluntary compassionate way. My allegiance was to Al Purdy and his wishes, not to the preservation of outmoded laws or the hypocrisies of Canadian politicians,” wrote Hofsess.

In 2002, Martens was charged with two counts of assisting the suicides of two women. She was acquitted in November 2004 for lack of evidence. But the authorities’ awareness made it impossible to continue, Hofsess wrote.

In the article, the former film critic at Maclean’s magazine describes how he was changed by the desperate suicides of Québécois filmmaker Claude Jutra and conductor Georg Tintner.

In 1982, Jutra, who had been diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease, read an assisted dying article written by Hofsess and asked for help ending his life. Hofsess put him off. Four years later, Jutra committed suicide by jumping off a bridge in Montreal.

Five years later, Hofsess established the Right to Die Society. In 1992, the society launched a constitutional challenge on behalf of Sue Rodriguez of North Saanich, in an attempt to strike down a section of the Criminal Code that made assisted suicide a criminal offence. The challenge was rejected by the Supreme Court of Canada in a 5-4 ruling.

In 1999, after Tintner, who was dying from a rare form of melanoma, jumped to his death, Hofsess went from advocating suicides to facilitating them.

“Let’s not mince words: I killed people who wanted to die,” he wrote.

In February 2015, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that competent adults suffering intolerably from “grievous and irremediable” medical conditions have the right to seek medical assistance to die on their own terms, and ordered the government to write a new law.

Victoria NDP MP Murray Rankin is vice-chairman of the special parliamentary committee dealing with the federal government’s response to physician-assisted dying. On Tuesday, Rankin said he found Hofsess’s story very powerful and emotional.

“I’m reeling from the story,” said Rankin. “It’s particularly poignant for me. Al Purdy was a high school classmate of my father’s in Trenton, Ont. And my dad spoke of Al quite a bit when I was growing up. I kind of feel like I know Al Purdy a little bit.”

What Hofsess was doing was illegal, but it shows that people have been working outside the law to find humane ways of dying for a generation, Rankin said.

“This whole underground that John has exposed demonstrates that the Supreme Court has led Canadian public opinion once again. They led us in the issue of abortion and same-sex rights. And it seems they are ahead of government again.”

On Thursday, the committee’s report, proposing access to physician-assisted dying at home, was tabled in the House of Commons. A new law must be in place by June 6 to meet the Supreme Court deadline, Rankin said.

“The fact that doctors are going to be involved in assisting with dying is so different from the story of Al Purdy and John Hofsess. This was self-help. It was completely against the law. Frankly, most of us would rather have the assistance of physicians if we ever get in this horrible situation.”

Rankin said he does not condemn Hofsess for his action. “I’m just wishing he didn’t have to go to Switzerland.”

The MP is hosting a town hall meeting on medical aid in dying on Saturday from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. at Oak Bay United Church.

Chris Considine, the lawyer who represented Rodriguez during her challenge, said Hofsess’s death is the passing of an era.

“John had been a major proponent of assisted death for people who were terminally ill at that time,” Considine said. “Thank goodness the law has changed so people who were in those difficult circumstances didn’t have to resort to those type of circumstances outlined in John’s article. Today, I think we have a much more humane society, which with the protocols that have been directed by the Supreme Court of Canada, will bring a lot of relief and comfort to terminally ill people.”

It’s too late for Hofsess, 78, who was diagnosed with prostate cancer and pulmonary fibrosis. He flew to Switzerland on Feb. 23 and died on Monday minutes after receiving an intravenous injection of the barbituate Natrium-Pentobarbital. “The latitude of Swiss law appeals to me — laypersons are permitted to assist voluntary deaths — and I wish to end my life in the company of good people,” he wrote.